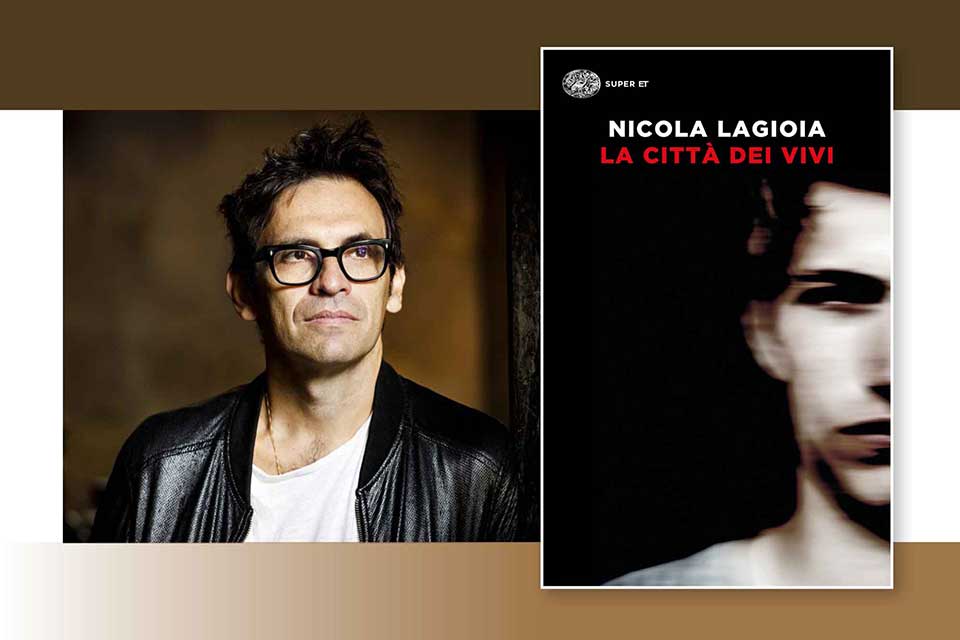

Frighteningly Normal: Investigating Evil in Nicola Lagioia’s La città dei vivi

Through the lens of a notorious murder case, Italian writer Nicola Lagioia paints a grim portrait of the city of Rome and its “desperate” youth and explores the reasons why ordinary people do monstrous things.

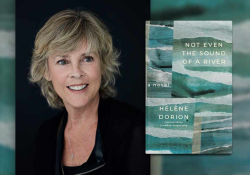

La città dei vivi (2020; City of the living), to be published in English translation by Europa Editions in 2023, is the latest book by Nicola Lagioia, an Italian writer whose previous novel, La ferocia (2014; Eng. Ferocity, 2017), won the Strega Prize—the highest accolade in the Italian literary world. Probably best described as a nonfiction novel (and often compared to Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood), La città dei vivi is a deep dive into one of the most famous murder cases in recent Italian history, the killing of twenty-three-year-old Luca Varani at the hands of twenty-nine-year-old Manuel Foffo and thirty-year-old Marco Prato. On March 5, 2016, after a three-day bender, the pair invited the young man to their home, drugged him, and tortured him to death over the course of two hours. In the aftermath of this apparently motiveless murder, Foffo stated that he and his accomplice had wanted to kill someone “per vedere l’effetto che fa” (to see what it’s like). Lagioia, who developed an obsession for the case, interviewed many of the people involved and studied court documents, interrogation reports, depositions, clinical records, and private correspondence. Many of these documents are transcribed in the book and interspersed with personal reflections by the narrating voice as well as fictional passages such as dialogues and internal monologues. The result is a narrative hybrid that is as disturbing as it is thought-provoking.

The case lends itself to lurid, sensational reporting, and, in the aftermath of the event, the Italian press often exploited readers’ morbid curiosity. Prato was a handsome, well-known event organizer in Roman nightlife—charismatic and warm according to some people, toxic and manipulative for others; Foffo, who had enrolled in university but never graduated, had unrealized dreams of making it big and some alcohol abuse issues. Their encounter created, so the narrative went, a sexually charged folie à deux: Prato, a gay man who often pursued heterosexual men, and Foffo, who had sexual relations with Prato while clinging to an image of himself as staunchly heterosexual, met up one night to consume large quantities of alcohol and drugs until they seemingly lost touch with reality. At an unspecified point in time, after two days and two nights had elapsed, they decided to act out a fantasy of rape and summoned Luca Varani, a young mechanic from the Roman borgate (suburbs) who occasionally prostituted himself, with the promise of easy money, but ended up killing him with knives and hammers. After sobering up, faced with the reality of his situation, Prato checked into a hotel and attempted suicide but was found in the nick of time with the help of Foffo, who in the meantime had turned himself in. Later, Prato did die by suicide in jail on the eve of the trial, while Foffo was sentenced to thirty years and is currently detained. The case fed into the Italian public’s obsession with cronaca nera (crime news) and spawned talk-show debates, theater plays, even a TV show currently in the works.

As is often the case with apparently senseless acts of violence, the main question raised by the book is “why?” or, more precisely, “how?” How could two ordinary young men, fairly well educated, raised by honest families and with so many opportunities at their fingertips, throw their life away in such a reckless manner by ending someone else’s? Was it the drugs, was it boredom, depression, self-loathing—demonic possession, even? All these hypotheses were entertained in public discourse in the aftermath of the murder.

True crime sometimes dwells on sordid details for their own sake, but, even in its most graphic pages, La città dei vivi refrains from any gratuitousness. Within the intended aim of this book, details are necessary, as each of them has the potential to add a vital piece to the puzzle that Lagioia is trying to put together. It is the ordinariness of the killers—how unremarkable their lives, their occupations, their families are—that makes it critical to pinpoint specifically where things took a turn for the worse. As Zygmunt Bauman puts it, “How safe and comfortable, cosy and friendly the world would feel if it were monsters and monsters alone who perpetrated monstrous deeds”;[i] instead, the book reminds us, evil often disguises itself in the unexceptional. For this reason, the stakes of Lagioia’s careful act of narrative reconstruction could not be higher. If two regular guys can slip into horror so seamlessly—Lagioia asks himself and us—how can we be sure we will not turn into monsters as well? In this sense, La città dei vivi tackles the age-old philosophical question about the origin of evil: unde malum? (whence evil?). Through its attention to detail and its sometimes excruciating precision, the book tries to explain the horror away, to isolate its germs, as it were, in the hopes of containing it in a neatly labeled jar.

La città dei vivi tackles the age-old philosophical question about the origin of evil.

At the same time, the author accepts the fundamental impossibility of this operation. The Varani murder reveals itself as a perfect case study for how human nature is ultimately always unknown to itself. “We can never hope to know everything about the people we are interested in,” the narrator is warned at one point, to which he replies: “We don’t even get to know everything about ourselves … otherwise nobody would write anything anymore.”[ii] To the narrator, the act of investigating is one and the same with the act of writing, and building a somewhat meaningful narrative is therefore the only viable alternative to chaos—the only way to get as close to the core of things as possible.

Notably, the book frames the killers themselves as unreliable narrators, and questionable interpreters, of their own story. In the confession given right after the fact, when the need to offload his conscience is still more pressing than any self-preserving calculation, Foffo begs for an explanation from the officers who are interviewing him. He does not recognize himself in the act he committed and is desperate to bridge the cognitive gap between his self-image and the label of “criminal,” which he finds absurdly incongruous when applied to him; he too, like the prosecutor who is interrogating him, is trying to uncover a meaning, a truth that is ultimately inaccessible. This creates the paradoxical situation in which the testimony of those who committed the act is as close to (or as far from) the truth as the investigators’ reconstruction of the event. The novel’s choral structure, whereby readers get to hear many voices (often with no introduction on the part of the narrator), contributes to the atomization of truth into many, often contradictory, versions.

The novel’s choral structure, whereby readers get to hear many voices, contributes to the atomization of truth into many, often contradictory, versions.

On one hand, this is a universal story, an inquiry into the ease with which the normal can become abnormal; on the other hand, there is a sense this story could not have happened anywhere but in Rome. The city is arguably one of the main characters in the book. Contrary to any picturesque depiction, the Eternal City described by Lagioia is only such because it is inherently posthumous, “a city where everything has already happened.”[iii] Its “dead beauty” is a sharp counterpoint to the garbage in the streets, the pests, the crumbling infrastructure, and the corruption of its political leaders.[iv] (When the murder took place, Rome had no mayor—the city council had been put under external administration for a corruption scandal—but had two popes, reinforcing the idea of a world out of joint, where even the unthinkable is possible.)

Rome is arguably one of the main characters in the book.

Among other things, Lagioia uses the murder to reflect on Rome’s social and economic disparities. The book explores the encounter and contrast between a generation of bored, privileged thirtysomethings, unemployed or with odd jobs, bailed out by their parents’ money and connections, and young people like Luca Varani, who grow up in the Roman suburbs, work thankless jobs to make ends meet, and sell their bodies for a little extra money. The narrator laments the fact that, in narratives about the case, Luca’s life circumstances—the fact that he engaged in prostitution and small-time drug dealing—were used as evidence that he was asking for trouble. Too often, in news stories such as this, the victim is reduced to their victimhood, to a two-dimensional role that erases their humanity, while the perpetrators and their motivations are obsessed over. It is to counteract this discursive laziness that the book gives as much attention to the killers as it does to Luca, rendering a complete, one might say respectful, image of his life through the words of the people close to him.

The class angle is a crucial point of contact between La città dei vivi and previous literary and cinematic representations of Rome as a place of hardship and misery, stagnation and inequality. The main point of reference in this respect is Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Roman works, namely the novels Ragazzi di vita (1955; Eng. The Street Kids, 2016) and Una vita violenta (1959; Eng. A Violent Life, 2007), and the films Accattone (1961; Beggar) and Mamma Roma (1962).[v] Pasolini’s social outcasts, thieves, and prostitutes exemplify the terrible living conditions in the Roman borgate in the postwar period but are also represented as the last stronghold of authenticity and vitalism in a progressively massified society. Their existence is often aestheticized, framed as a balancing act between high and low, abject and sublime. “Mo’ sto bene” (Now I feel fine), says the protagonist of Accattone as he dies on the concrete, Christ-like, after being chased by police while the strains of Johann Sebastian Bach can be heard in the background.

In La città dei vivi, Luca is granted no such moment of final reconciliation, and his death does not lend itself to any allegorical reading. The point of the book, and the simple yet mystifying fact that it tries to make sense of, is that he was nothing but an ordinary guy who was killed by two ordinary guys. As the narrator sums up, “No human being is worthy of the tragedies that befall them.”[vi]

University of Oklahoma

[i] Zygmunt Bauman, Collateral Damage: Social Inequalities in a Global Age (Polity Press, 2011), 134.

[ii] Nicola Lagioia, La città dei vivi (Einaudi, 2020), 436.

[iii] Lagioia, La città dei vivi, 269.

[iv] Lagioia, La città dei vivi, 6.

[v] While the book does not explore this genealogy in detail, it is discussed in the homonymous podcast curated by Lagioia (La città dei vivi, Chora Media, 2021–2022, accessed October 6, 2022).

[vi] Lagioia, La città dei vivi, 43.