An Interview with Iranian Poet Mohsen Emadi

Persis Karim: Can you say a little about what finally made you leave Iran? Were you threatened with imprisonment? I know you left in 2009, but in the interview you did with Lyn Coffin, your translator, you were a bit vague. I wonder if you can elaborate a bit.

Mohsen Emadi: I wasn’t sure if I had to leave Iran or not. I resisted for years, trying to continue my resistance inside the country. Many of my friends left Iran right after the defeat of the Iranian student movement in 1999. I had some threats, like being questioned for my talks outside of Iran in 2007 and 2008, house searches, and so on, but they weren’t serious. From the time I was a young student at Sharif University, I was active in several political and literary movements of the time. Going to jail for a few months was something predictable. But what actually forced me to leave was the reality that the country was in ruins: a land without morality, without hope, a land characterized by betrayals, the impossibility of working in the public sphere, the expansion of literary mafias, the lies and superficiality of the government in every aspect, personal and public—the type of experience you find in Herbert and Miłosz after their exile. For two months in 2009 I took part in all the demonstrations of the Green Movement, and I witnessed the brutality of the government in the streets—the dead, bullets, tear gas—and I was sure the regime would not bow to the will of the people. So I left with a small hope of return, but this simple hope turned out to be impossible because I became more radical in my writings, talks, and interviews after they killed some of my loved ones in Iran.

PK: Had you been outside of Iran before 2009 for any extended period of time? And when you left in 2009, did you think of it as leaving permanently, as a form of exile?

ME: Actually, my first book was not published in Iran. It was published in Spain and in Spanish, around 2003. Therefore, I was going to Spain for poetry festivals and received a few writer’s residencies (one or two months each time). I also visited Turkey, sometimes for my research on Rumi and sometimes to meet some Turkish poets who were my friends. Yes, I now think I have no chance of returning. I’ve changed a lot. I passed through a period of self-criticism, and therefore my critiques on Iranian culture are as harsh as the ones I level against myself. Here, I had the chance to develop a deep friendship with the late Juan Gelman, and I think he influenced me a lot. He never returned to Argentina, and even last January when he died, we scattered his ashes in a village in Mexico, his country of exile. He was buried, without a tombstone, in exile, and I imagine the same thing for myself.

PK: How have your wanderings around the globe affected your sense of who you are, both as a man and as a poet? Why did you finally end up in Mexico?

ME: As a poet, I try to embrace the world, to discover the rhythms of different languages, cultures, and geographies. Finland, the Czech Republic, and Spain continue their lives in me in the same manner that Iran is still part of me. I look at myself through other subjectivities, the subjectivity of snow, of lakes, friends, and languages. I have also tried to translate the poetry of all the regions in which I’ve lived. And their poetry has changed mine. They became mine. Like Rumi, I love Holan. Like Shamlou, I love Cernuda and many other poets.

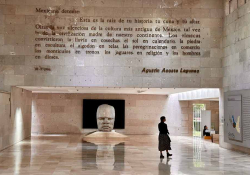

I have several publications in Spanish: some books, as well as several anthologies and journal publications. The Americas were unknown to me until recently. I came here because I was curious. I had translated some Latin American poetry into Persian, but I wanted to touch its body and live its poetry. Luckily the ICORN residency program offered me a place in Mexico. I arrived here, and little by little it has become my home.

PK: You seem so comfortable in Spanish—had you studied Spanish? How has translation afforded you the ability to adapt to new settings, new countries, even new languages?

ME: For years, I refused to learn Spanish, until I met Antonio Gamoneda at a poetry festival in Granada and his poetry and his presence motivated me to learn it. I knew a bit before, but that was not sufficient for living and writing in a Spanish-speaking world. From 2010, I tried to inhabit that language. I guess I learn languages quickly, and now I am learning Brazilian Portuguese because I want to revise my translations of Andrade and Melo Neto from the original.

PK: How has your work on the late Ahmad Shamlou, the celebrated poet of Iran, either in preserving his legacy or in terms of your own attention to folk poetry and folklore, helped you to share his work and also kept you connected to Iran and to the Persian language?

ME: Shamlou will always live in me, as a mentor and as a poet. I loved him. He was one of the most important figures of Iranian poetry and one of the most important people I have met in my life. His presence for me is as influential as the presence of Gamoneda or Gelman. I still read and reread his work, and he always surprises me. I was so fortunate to know him. I believe the intensity of his voice, his poetry, and his character is the depth my country has lost and must regain.

PK: Are there ways of being and things that have surprised you about your “exile” that you would not have considered before you actually left Iran?

ME: Everything surprised me when I left, even my own poetry. More than all the objects I’ve seen or places I’ve been, I’ve been surprised by language and what it does. I always think about objects and their naming—how a tree is called tree, árbol, or derakht and what lies in the abyss between these words referring to a single object. I wonder every day about my strength and my weakness, my dreams and myself.

January 2015

Born in Iran, Mohsen Emadi is the award-winning author of four verse collections and numerous poetry translations; the poems featured in the print edition of the January issue come from a collection called “Standing on Earth.” Emadi is the founder and manager of Ahmad Shamlou’s official website and The House of World Poets, a Persian anthology featuring more than five hundred international writers. He currently lives in Mexico City.