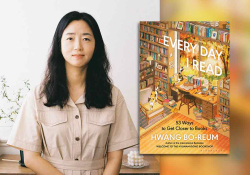

The Origin of the Milky Way

A writer-activist leaves his Brooklyn apartment and goes to Manhattan for a Queer Nation protest at the Russian consulate carrying his laptop, Charles Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop, his own history of activism, and his memories of his father, who once worked on Olympic coverage in Russia for NBC. With the Freedom Tower looming ahead, he rushes to pay his electric bill before joining other demonstrators calling for boycotts of Russian vodka and the 2014 Olympics Winter Games in Sochi.

My mother has walking pneumonia. Here’s what she plans to do about it: “I’ll walk,” she says. It’s called ‘walking’ pneumonia, isn’t it? It’s not called ‘crouching’ pneumonia. It’s not called ‘lying down’ pneumonia. It’s not called ‘sitting on your ass and watching Bill Maher all day in umpteen reruns until you feel like you can never for the rest of your life look at another blonde Republican bimbo’ pneumonia. It’s called ‘walking.’ You walk. Especially if you have a dog,” she says. “Then you both walk. I have to. Every day, four times a day, sometimes five, I have to walk the dog. She walks, I walk, she walks me. If not for that dog, I’d never walk at all. If not for that dog, I’d be dead now like your father and you’d have eighty-two years of my accumulated junk to wade through and cart off and sell on the street and try to fit into your tiny, hot apartment. Walking, okay? You ask me how I’m doing, I’m walking. The dog and I are walking.”

I’m tying my shoes, cell phone in the vise clamp of cheek and shoulder. How I miss the rotary phones that hung on the walls of kitchens, with their long coiled cords and thick handsets sometimes swollen with a growth of plastic meant to hold your head up while you talked and walked around the room and did what people do in kitchens.

“Didn’t you read my email?” my mother says.

“Yes, yes, I did,” I say, shoes tied and double knotted. Heading out now. I look around the room for pocket stash, dollar bills, loose change, Metro-Card, pens, keys, where are my keys? In a jar by the door. Cell phone’s in my hand, of course.

“If you’d read my email, you’d know about the pneumonia.”

“I read your email,” I say, lying. Why go through the trauma of birth if not to lie to your mother?

Keys are not in the jar by the door.

“What did the doctor say?” I ask.

“Doctor?”

“Didn’t you go to the doctor?”

“I’m from Colorado, I don’t do doctors. We bury our dead by the side of the wagon train and move on.”

“You must’ve talked to a doctor if you know you have pneumonia.”

“Walking pneumonia,” she says. “Why don’t you read your email? I put ‘pneumonia’ in the subject line. All caps. It’d take a special effort to miss it.” Keys not on the desk, not on the counter next to the stove. Not on the stove. Not in my hand already or my pockets. Not in the bathroom sink. Not in the bed.

“Your brother was here on Sunday,” she says. “That’s how I know.”

My sister-in-law is a nurse. She diagnosed my mother on Sunday. Then they took her out to dinner, Italian, my mother tells me.

The keys aren’t under the bed. They aren’t in my knapsack.

“So you’re fine,” I say.

“I’m not fine, but I’m walking, I just said.”

Keys are caught in the folds of the umbrella jammed into the jar by the door. Their hiding place.

“Men don’t listen,” she says.

“I’m listening.”

I’m listening, and I’m heading for the door, keys in hand, shoes tied, pockets filled, laptop and the Charles Dickens novel from 1841 that I will never finish reading stashed in my knapsack, which is slung on my back. The novel is The Old Curiosity Shop. “Night is generally my time for walking” is its first sentence. I walk down the narrow hall to the doorway and out into the light, lock the door, turn around, face the world. It’s not night, it’s not London, it’s not 1841; it’s August in Brooklyn, in front of my ground-floor apartment in a brick townhouse in Park Slope, early morning, right now, and the sun’s bright and the sky’s blue behind the clouds, which are drifting and puffy and white, like me.

“I’m on my way to the train,” I tell my mother.

“Fine. Hi to the train.”

“I’m headed into Manhattan.”

“Are you seeing Woody Allen’s new movie?”

“I’m not.”

“Go see Woody Allen’s new movie.”

“I want to. Not now. It’s 9 a.m. Go to the doctor. The reason you moved to a fancy condo in an expensive retirement community in Philadelphia was so you could pull that cord on the wall if you needed a doctor.”

“I’m not going to pull the cord.”

“That’s what you’re paying for, so you can have a cord.”

“I’m not pulling any goddamned cord.”

“Listen,” I tell her.

She tells me I’m the one who doesn’t listen.

“Listen,” I say again. “I’m at the train.”

I’m not at the train. Not the train I want to take. I’m at the corner of Union Street and Fourth Avenue, where the R stops, but I'm heading north toward Bruce Ratner’s sports arena, the Barclays Center, which is rusty and new, humped and curvilinear with a hole in its head, like a cross between a giant pierogi and a bottle opener.

“You listen,” she says, speaking slowly and emphatically. “If I pull the cord. They will send. An ambulance. They send an ambulance if you so much as stub your toe. It’s not that they care about you. It’s that they do not want to get sued. I am not getting. Into any. Ambulance. That’s what killed your father. He was alive when he got in the ambulance. When he got out, he was not. I have aspirin, and I have my dog.”

“Okay,” I say. “I need to go.”

“Okay,” she says. “Thanks for calling. See the Woody Allen movie,” she says, and then she hangs up.

And I’m alone in Brooklyn.

Gowanus, Brooklyn, an ancient marshy swamp that hipsters are probably already calling GoBro. It’s the floodplain that waters surge across in hurricanes.

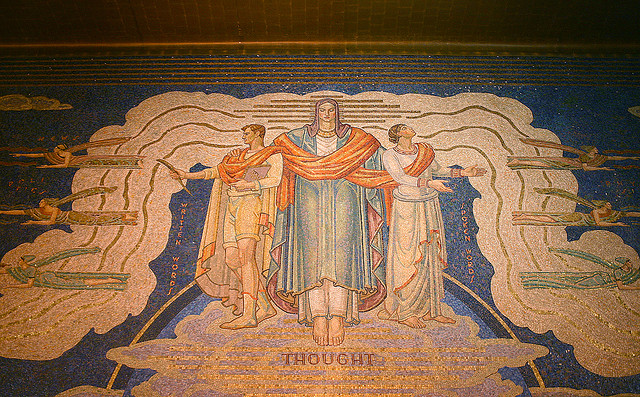

I’m watching from a Brooklyn corner. The sky is Tintoretto blue, the color of the heavens in Tintoretto’s Origin of the Milky Way, where Jupiter sneaks his love child Hercules to sleeping Juno’s breast, and the milk that Juno spills in surprise makes the Milky Way.

In the distance, anchoring Manhattan, is the Freedom Tower, the tallest building in the Western hemisphere since May 10, “third tallest building in the world by pinnacle height,” Wikipedia says, at least until a bunch of towers in China and South Korea and Saudi Arabia are finished. Ironworkers from East Flatbush and Forest Hills, in hard hats and chartreuse safety vests, bolted the final length of spire in place on a spring morning while helicopters watched.

I’m watching from a Brooklyn corner. The sky is Tintoretto blue, the color of the heavens in Tintoretto’s Origin of the Milky Way, where Jupiter sneaks his love child Hercules to sleeping Juno’s breast, and the milk that Juno spills in surprise makes the Milky Way.

The Freedom Tower is an empty phallus, hollow and jutting and just done, peeking out between a Hess station and a billboard for gin. Its telecommunications peak is triangulating with the round-headed tip of the Williamsburg Bank building and the steeple of the St. Agnes Church on Sackett Street, in Carroll Gardens.

The Williamsburg Bank is set at an angle to Fourth Avenue, and so is the billboard for gin. Everything in Brooklyn is catty-cornered and slightly askew, meaning also me. I’ve got three things to do by noon. I have to pay Con Ed so they won’t turn out my lights. I have to buy a liter bottle of water to take to a Queer Nation protest at the Russian consulate on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where two bartenders will pretend it’s vodka and pour it in the street, so Vladimir Putin knows that if he fucks with gays in Russia he can forget about selling liquor in New York. (Putin’s at war against the gays, maybe you’ve heard.) And I have to stand in front of the Russian consulate in a strip of pavement cordoned off by police barriers and chant, “We’re here, we’re queer, we’re only drinking beer.”

Plus, like my mother, I need aspirin—not because I have pneumonia, but because my heart won’t stop beating. It beats, oh it beats, all the time. Either I’m anxious, or just alive. Or I’m thick-blooded and heart-struck and headed for death, not in the way we all are, but right now on a Brooklyn corner, before I have a chance to pay my light bill, and I’ll die in debt, which will really bug my mother.

Water and aspirin, no vodka: my shopping list. I nod to the billboard for gin and to the big mural of eight women who are dancing and painting and reading and stargazing on the side of a tenement building facing the Hess station. Then I walk to Flatbush Avenue and call my brother.

Everything is fiction but New York. I’m not true, either. The skyline of Manhattan is true. I know the buildings are there, because I watched some of them fall, in real time in the actual world.

Unlike me, he answers his phone.

“Your mother says she has walking pneumonia,” I tell him.

“I know,” he says. “I was there. We took her to dinner. Did your mother tell you that?”

“She said Italian. I assume that means Olive Garden.”

“Where are you?” he says. “Why are you calling me?”

“I’m in Brooklyn,” I say, which sounds untrue. Before last March, I lived in Manhattan for thirty-three years. Life span of Christ.

“Is your mother okay today?” he asks me.

“She says she’s okay.”

“She was fine on Sunday.”

“She’s always fine. She gave me the wagon train speech. You’re mad at me.”

“I’m not mad. Why would I be mad?”

“I'm sorry I couldn’t go down there on Sunday. Blame Putin. You know, he’s got a problem with the gays, and—there’s this thing I’m doing today the Russian consulate, and—”

“I know about Putin, please. Are you getting arrested on TV? Will I have to watch that? I hope you’re wearing a clean shirt.”

“I am, actually. Clean and new and sort of guacamole green.”

“I’ll keep my eye out.”

“Call your mother. She sounded okay to me, but—”

“I’ve got someone on the other line,” he says, and he says, “Bye,” and I say, “Bye,” and that’s not true, I made it up. Both phone calls, they’re impressions of the truth. Everything is fiction but New York. I’m not true, either. The skyline of Manhattan is true. I know the buildings are there, because I watched some of them fall, in real time in the actual world. Even Brooklyn is true, especially Flatbush Avenue at Nevins Street—One Nevins Street, Con Edison’s Brooklyn office.

“You can’t pay here,” they say, when I walk in the door waving my turn-off notice at the bald reception guy and two women in plum and aqua Hillary Clinton pantsuits behind a foldout table.

“If not here, where?” I say.

They grin and shake their heads and point to the reception desk, where a stack of flyers gives an address on Jay Street.

“How far is that? I’m new here. Can I get there by candlelight?”

Sure, I could get there by candlelight. Or I could walk ten minutes from here to Jay Street through the Fulton Street mall.

Or I could pay my bills on time. I could pay my bills online. I could get “direct deposit” and feed my paycheck straight into my bank account and manage my finances from a palm pilot. But I like to stand in line at payment centers and check-cashing windows, clutching my angry bill and my few dollars, or my payroll check and my ID—passport, driver’s license—waiting with New Yorkers.

For a long time in the 1980s and ’90s, I worked temp jobs at terrible investment banks and law firms in Wall Street and Midtown, clacking away at a Wang keyboard in word-processing centers staffed with gay guys and black and Latina women, the secret economic engine of the world financial market. Friday afternoons you got your timesheet signed and ran to Tiger Temps or Career Blazers, where you traded it for a paycheck, and then raced to the back of the line at the nearest check-cashing place.

Here’s one way in which New York is true: It has a simple plot. Will I get to the cash window in time? Will they take my check? Have they turned off my lights yet?

I walk through downtown Brooklyn on a weekday morning past commuters and early risers and a shirtless guy doing chin-ups on a street sign. At the MetroTech Center, I feed a C-note into a Con Ed touch screen. The machine does not make change, and it gulps down my whole bill and spits out a receipt. Then it flashes a message: “Service interruption pending. See a Con Ed representative.” Which means another line, another wait, long enough to read a chapter of The Old Curiosity Shop. Little Nell isn’t dead yet. Neither am I. My heart’s still beating, and suddenly I’m standing in front of a guy at a waist-high podium who takes my receipt and staples it to something else and hands it back.

“That’s it?” I say.

“Your next bill is due on the eleventh,” he says.

“They won’t turn my lights off?”

“Pay your bill on the eleventh.”

“So I’m cool?”

He looks at me for the first time. “You’re cool,” he says, in a tone that means I am not at all cool, but I have lights until the eleventh.

Lights, check. Call your mother, call your brother, ask your brother to call your mother, check. Now I need water and aspirin and a train to Manhattan.

I take the A train, nearest option, under the East River to the tip of Herman Melville’s isle of the Manhattoes—the financial district, always a disaster area. The Dutch show up in the harbor, it’s a disaster for the Algonquins. The British get there next, it’s bad for the Dutch. Yankee rebels act up in 1776, the British burn the city to the ground, from Broadway to the Hudson. In 1835 a freak fire destroyed everything from Broadway to the East River, including the insurance industry, which fled to Connecticut, and that’s why Hartford and not Lower Broadway is the Insurance Capital of the World.

The train stops at Fulton Street, centuries of loss overhead. Shakespeare riots, 1849. Draft riots, 1863. You know the rest. I switch to the #5 Express up the East Side. I love trains, I am never mad at the MTA. When Sandy shut down the subway system last fall, I longed for its return the way Christians say they want Jesus back.

At East Eighty-sixth Street, I climb to the daylight, where I find water. The woman behind the counter at the greengrocer rings up my liter bottle of Poland Spring and says, “Great book,” pointing to my hand. I didn’t realize I was still holding The Old Curiosity Shop. I’m not sure if she’s asking or insisting. Should I tell her I think Little Nell is sort of a drip? Immersed in quandariness, I grab the water, smile, and flee, forgetting about the aspirin until I reach the Russian consulate, where the Queer Nation demo is about to begin.

The choreography of resistance is specific, though its movements vary depending on the size and complexity of the protest. There are constants, certainly, at picket sites. There’s a staging ground where you gather your crew, hand out signs, distribute fact sheets and flyers. Eye the police. Maybe there are a lot of police in riot gear and mounted on horseback, standing in line, holding their billy clubs. Maybe there are six bored police officers on a weekday morning drinking coffee out of deli cups.

If it’s Manhattan, or a city with a grid of streets or busy downtown, there’s sidewalk traffic, tourists or daily commuters or habitual onlookers, sometimes penned behind police barriers across the street or down the block, sometimes walking past and reading your signs and standing in line with you at the coffee wagon that a resourceful small business guy has just rolled up.

Or the protest site is remoter. Once in January, in a small town in New Jersey, for the benefit of three police officers and a shivering reporter from the local suburban paper, I lay on the pavement in front of a pharmaceutical company with my arms spread wide as if in crucifixion and linked to my friends’ arms through hollow metal piping that we wore like sleeves.

Twenty of us, maybe. There was no way to get us off the ground and handcuffed and loaded into police vans without sawing through our arms at the shoulder. We chanted to the morning air, “Release the drugs, AIDS won’t wait.” When we got up and moved to another spot, we were a long line of conjoined tees—small “t,” our heads above our spread arms.

Another time, with a couple hundred other AIDS activists and ACT UP and Queer Nation members, I got stormed by mounted police, who backed us against the wall of the New York State Theater—now the David H. Koch Theater—at Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, along Columbus Avenue.

I knew it was bad news to get near a horse who was nervous in crowds, but there was nowhere to go. We were pressed to the wall. Governor Cuomo (Mario, then) was at a benefit performance at Avery Fisher Hall, and we had come to shame him for his lousy record on AIDS—to raise our arms in the air with our fingers pointed and chant, “Shame! Shame! Shame!”

It was nighttime, the demo was done, floodlights were shining brightly, the horses were brown and their riders were blue, and we were pinned and lit like a mob scene in a Russian film about the revolution, while the horses’ hooves made echoing sounds on the concrete.

Speaking of Russia, here’s a fact sheet from the Queer Nation demo at the Russian consulate with news about Vladimir Putin’s government, which you already know if you read Harvey Fierstein’s New York Times op-ed piece on July 21:

On June 30, 2013, Putin signed a law to arrest tourists who are “suspected homosexuals.”

On June 30, 2013, Putin signed a bill that threatens jail for Russian citizens who offend “religious believers.”

On June 30, 2013, Putin signed a bill that fines any Russian for revealing to children age eighteen and under the existence of “nontraditional sexual relationships.”

On July 3, 2013, Putin signed a law banning the adoption of Russian-born children by same-sex couples or anybody living in a country where gay marriage is legal.

According to these laws, Putin might conceivably arrest the pope.

And there’s talk that Putin is about to sign a law taking children away from parents who are lesbian or gay, or suspected of being lesbian or gay.

That’s why I’m at the Russian consulate. Also because the 2014 Winter Olympic Games are being held in Russia, and it seems a bad idea to send gay athletes to a country where they could be arrested for saying they exist.

The demo starts. We shame the Russian consulate. We stand, we chant, we walk in a circle. We raise our fists and look angry for photographers. We hold signs saying “Boycott the Olympics” and “Boycott Russian Vodka.” Somebody shouts, “Drink Grey Goose, it’s French.” We pass leaflets, we give interviews, we watch a pair of bartenders in red shirts from a gay bar in Midtown pour vodka into the street and onto the Associated Press reporter’s “vodka cam,” which lies on the pavement and stares up at the liquor stream.

I’m a bourgeois subject from Brooklyn with a Dickens novel and a protest sign. Brooklyn is where bourgeois subjectivity comes from. So is the nineteenth-century novel, according to Ian Watt. (Google it.)

The demo is done in an hour. Information gathered for the five o’clock news shows, shots taken, reports filed, protesters inspired, workers at the construction site next to us edified or annoyed or eating lunch. Everyone packs up and goes home. Some demos end fast. “People come and go so quickly here,” I think, and I’m alone again on a corner in New York with my bottled water, which I forgot to give to the cute bartenders, and no aspirin, and still a beating heart, and my new green shirt, and a sign that says “Queers Say Nyet” against a rainbow flag. The flip side says, “Boycott the Olympics.”

I’m a bourgeois subject from Brooklyn with a Dickens novel and a protest sign. Brooklyn is where bourgeois subjectivity comes from. So is the nineteenth-century novel, according to Ian Watt. (Google it.) A novel needs a plot twist, and here’s mine:

NBCUniversal owns broadcast rights to the 2014 Olympic Winter Games in Sochi, “across all media platforms, including free-to-air television, subscription television, Internet and mobile, in an agreement valued at USD 4.38 billion,” according to a press release from Olympic.org. Queer Nation—that’s me, among others—is calling for a boycott of the Sochi Games.

The only time the US boycotted an Olympics was the Moscow Summer Games in 1980, when Russia invaded Afghanistan and President Carter pulled us out of the competition. It was the biggest disappointment of my father’s career. My father worked for NBC TV—then still a subsidiary of RCA—for forty-five years, during the last fifteen of which he was vice president of operations and engineering for NBC’s coverage of the Olympics. In 1979 and 1980, he flew to Moscow fourteen times to plan for TV coverage of the games. “How are things in Russia, Jack?” my parents’ friends would ask him. “Russia” still meant the USSR. No one we knew had ever been there or come from there. My father’s trips were thrilling and mysterious, and he would drop his deep voice even lower and say, “Well, let me tell you about Russia.”

Then history happened, oops. In my family mythology, the 1980 Summer Olympics are a punch line in a Chekhov play. “Ah, Moscow.” Code for “loss.” In our house, the iconic Olympic rings are a symbol of the Dead Father. How many ashtrays, paperweights, fountain pens, duffel bags, warm-up jackets do I own—stashed away in desk drawers and top shelves—that are emblazoned with logos for NBC and the Olympics?

For a while, at NBC and elsewhere, my father’s name was synonymous with the Olympics.

Two years ago, when he was inducted posthumously into the Sports Broadcasting Hall of Fame, my brother and I made a video about his Olympic career, for a ceremony at the Hilton Hotel, and Frank Gifford clapped, and Howard Cosell’s grandson shook our hands.

My father’s name is John Weir, though people called him Jack.

This Oedipal drama is what I’ve been acting out my whole adult life.

Plus, my brother is a video editor who went to five Olympics and won two Emmy Awards for the work he did there. He’ll be at the Winter Games in Sochi next February.

Unless somebody and his queer friends gets them called off.

Is the personal political?

When my father died, I was in Jackson Heights eating dinner with a friend. My brother called me. For once, I answered my phone. Somehow, I knew. At the time, I was living in Hell’s Kitchen, not far from Times Square, and my subway stop on the way home from Jackson Heights the night my father died was his stop, Forty-seventh Street Rockefeller Center—the D, M, and F station under the RCA building, where my father came and went for forty-five years on his daily commute from New Jersey. When I was a kid, he worked on the sixth floor, down the hall from Carson’s old studio. When he ascended to Olympics tsar, he moved up to a corner office with a big window on the twenty-sixth floor.

My brother said he’d pick me up in Midtown that night. It would take him an hour to get to the city from the suburbs, with his wife, in their minivan. I reached Rockefeller Center in twenty minutes on the F train. I had time to kill. “Kill,” weird word. I didn’t know what to do. I never had a father die before. A lot of people had died, but not my father. I was gay in the ’80s in Lower Manhattan, I knew that people died, and how they sometimes died.

I wondered if it was too soon to wonder if I would miss him. I never really knew what he was like. My mother, I knew. I was her gay son; she had raised me and trained me to watch her and listen to her and say what she was like.

I’m sort of her. Big chunks of my personality are her, especially when I’m walking around Manhattan, where she spent half of every year for the last twenty-five years, in an apartment in Midtown—from which, for a long time, she walked up and down Manhattan—until she and my father sold their apartment and their Jersey farm and moved to a retirement village outside Philadelphia, where my father promptly died, leaving my mother home alone with a dog and walking pneumonia. She would not take cabs. She said subway stairs were hard on her joints. So she walked on relatively flat land. “It’s good for my arthritis,” she said, or insisted. If she walked all day, she said, her spine wouldn’t freeze, and she would be able to get up the next day and keep walking.

My mother walks, and I walked upstairs outside to Sixth Avenue the night my father died and put my hands flat on the side of David Sarnoff’s building, the RCA building, don’t call it the GE building, that’s blasphemy. David Sarnoff founded RCA. He was Russian—sorry, Belarusian: Дави́д Сарно́в.

I stood against the building, the tenth tallest building in New York, thirty-third tallest in the USA, says Wikipedia. Opened in 1933. Two years younger than my mother, five years younger than my father.

I thought if my father had a soul it would pass through here. I thought if I had a center it was Rockefeller Center. I stood in the portico of the Sixth Avenue entrance and looked up at a glass fresco called Intelligence Awakening Mankind, designed by a guy named Faulkner, Barry Faulkner. It’s not the famous mural with a picture of Lenin that Diego Rivera painted and Nelson Rockefeller had destroyed and hacked from the wall in the back of the building at the Rockefeller Plaza entrance. But I remembered my father walking in and out of these doors, onto Sixth Avenue, in his Mad Men black suit and white shirt and skinny tie in 1965. And I stood in the entrance and said good-bye to him, good-bye to a building.

My father is a building, and my mother walks around it.

They met at NBC, where they both worked, in 1952.

That’s why I’m here.

My adult life is an intervention against the media that made me.

What am I supposed to do about that?

It’s 2013, my father’s dead, my mother’s eighty-two and walking. I lean down and pick up a discarded copy of Queer Nation’s fact sheet, which you read already, up above. NBC is going to the Olympics, it says. Where am I going? More protests, no doubt, but not yet. Right now, I have water. I have Charles Dickens. I reach inside my knapsack and get out the bottle of Poland Spring, twist the cap, take a drink. East Ninety-first Street has returned to its daily rhythms, no longer the scene of struggle, but a side street off Fifth Avenue where workers are doing construction. Later, there will be stories in the news about Russian vodka and Putin and the Winter Games in Sochi. There will be shots of the crowd, including me. My mother and brother will watch the TV reports, maybe I’ll get phone calls. In the meantime, I should head home. I stuff the fact sheet into my knapsack next to Dickens, walk to Times Square, and take the Q train to Brooklyn, where I’ve got light until the eleventh.

Brooklyn, New York