Rediscovering Soyinka on Ebrohimie Road

Inspired by a photo and the histories connected to it, a writer makes a film to mark Wole Soyinka’s ninetieth year.

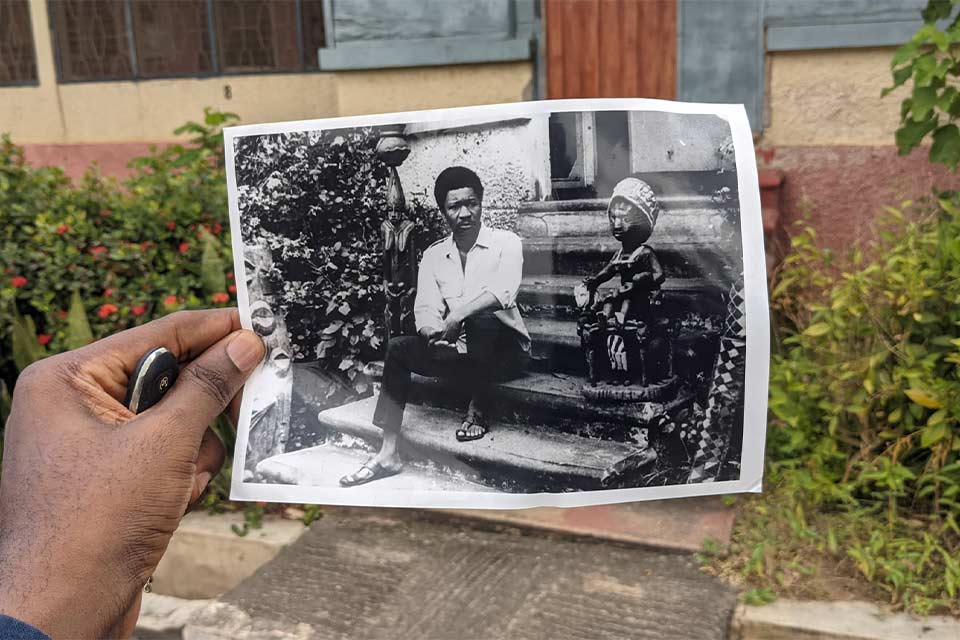

The photo of a young man of thirty-five, on the front page of Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years, had fascinated me for years. Wole Soyinka (b. 1934, Abeokuta, Nigeria), then an acclaimed playwright, sits with his hands crossed on the steps of a house. He wears leather sandals, one that wraps around his big toe. He is flanked by two gnomelike sculptures. The one to his left—and to the right of the photographer—sports a Yorùbá cap, likely put there before the photo was taken. The one to his right seems to be firmly rooted in the ground beside the steps but is tall enough to show up in the photo as if it’s placed right behind the man, to the right.

Something about the way the writer appeared, his eyes cast slightly askance toward his left but gently avoiding staring at the camera, is striking. When it appeared on the cover of his 1994 memoirs, the writer had become world-famous not just for his Nobel Prize but also for his handsome gray Afro. Seeing the writer so young, so confident, so full of intensity and in such a casual look and environment invited my strong interest.

Something about the way the writer appeared, his eyes cast slightly askance toward his left, but gently avoiding staring at the camera, is striking.

There are other details in the photo—the hedge that intrudes slightly into the shot from the photographer’s left hand, the position of the writer’s legs (one foot lower than the other on the steps), the slight view of the open door of the house behind him, and the crack in the concrete at the top of the step, placed in the photo approximately near the writer’s left shoulder.

Perhaps because history is made material only by what we see, I had depended on photographs to aid my memory-reconstruction of events and places I had never seen but only heard about. And every time I came across my copy of the book, which got progressively worn over the years, I stared at the photo and noticed one new detail or another. My first copy had been bought by my brother; I don’t know if he ever read it. He admired Soyinka from afar as a political activist, read all the essays he wrote in the newspapers. This was during the military regime of Sani Abacha, during which time Soyinka was either in exile or about to begin one.

So one day, when I found out that the photo had been taken at the University of Ibadan, my alma mater, my interest became more intense. This was about a decade ago. I had graduated from UI, come to the United States for a Fulbright program, and completed my master’s degree in linguistics and teaching English. It was during one of my visits to the university staff club when a colleague mentioned, during a conversation, that the house where that famous Soyinka photo was taken was at the university. Not just that, but it was still habitable, and accessible.

I also learned a few things about the circumstances behind the photo. It had been taken in 1969, shortly after the subject, Soyinka, was released from his prison detention for participating in activities that the Nigerian military government found unacceptable during its conduct of the civil war against a breakaway region then called Biafra. Soyinka had not only visited Biafra in the early days of the war, he collaborated with a few rebels who had distanced themselves from the breakaway region and were now intent on creating what was called a “third force” to neutralize both the Biafran rebellion and Nigerian state aggression. Returning from Biafra, Soyinka was arrested and locked away without trial for almost thirty months, much of which he spent in solitary confinement. Upon his return, he granted a few interviews to journalists, one of which was with the journalist who likely took that photo. In a few years, Soyinka resigned his job at the university and embarked on a voluntary exile, during which he wrote his seminal prison pamphlet/memoir, The Man Died (see Books Abroad, Summer 1974).

All this history converging on my presence in the University of Ibadan stimulated me. Soyinka had been employed here as the first indigenous director of the School of Drama. His appointment began in 1967 shortly before the war began and ended shortly after his release and resignation. So the details of his productive presence at the university were always a matter of conjecture. How long did he stay after his return from prison? What was it like when he was gone? Why did he resign, beyond the issue of the war? As a student of this university, I had heard stories, none of which were conclusive. Some said he was pushed out because of his involvement with politics. Some said it was his temperament. Others said it was his personal decision, which he himself had written about. But in each of these writings, there were different reasons. In one, his marriage had been strained and he wanted distance. In another, his collection of carvings, which beautified and decorated his house—and that famous photo—had been stolen one after the other while he was gone, so he no longer felt welcome. In another narrative, the political situation on campus after his return made it hard to remain there. And in yet another, corroborated by some of his colleagues, the decision of the university to not officially confirm him as a full professor upset him and led to his resignation.

When Soyinka lived there, the veranda was open. Now it was boarded up and locked.

That same evening, I went there. The hair on my neck stood up as I approached it from the quiet junction at Landers Road. Ebrohimie Road, where the house lay at its farthest end, was gently wooded and—during the evening—was nearly empty of people. The sign at the beginning of the road read “Ebrohime,” missing an “i,” but it was also crooked and almost obscured by the overgrowth. The house was there all right, sturdy and almost unrecognizable. A few changes in the façade had been made, reflecting the security concerns of today’s Nigeria. When Soyinka lived there, the veranda was open. Now it was boarded up and locked. There didn’t seem to be anyone at home, but the frontage looked almost exactly as it did in the photo.

I would return there a few more times, each time discovering a new detail that wasn’t there before. On one of my later visits, I took along a copy of that original photo from 1969. And then I met the current occupant of the house, also a professor in the English department. On this day, for the first time, I noticed something I hadn’t seen before: a crack on the concrete near the top of the steps had remained there since that 1969 interview, as it was in the photo I held.

I would return there a few more times, each time discovering a new detail that wasn’t there before.

So one day, a few weeks later, when I excitedly emailed Soyinka himself an idea that had been bubbling in me since I first saw that photo, the crack would prove useful. It turned out, I found, that Soyinka himself had lost memory of where the original photo was taken. He was absolutely sure that it was somewhere else in town, long before he came to the University of Ibadan. The mistake made sense, when I thought about it, because the book, Ibadan: The Penkelemes Years, on which the image was first used, covered an earlier period between 1946 and 1965 when Soyinka first lived in Ibadan as a Rockefeller Fellow, wrote some plays, and got into trouble with the Western-backed Nigerian political establishment. It was easy to associate a cover image with the events of the time. But when I showed him the crack on the concrete, and—something else I had also found—a short video from Reuters showing him on the steps answering questions from the same journalist, he finally acquiesced.

The idea I shared with him, however, was met with stone-cold rejection. How great would it be, I mused, to have the great writer himself, now in his old age, return to the steps of that building to retake the famous photo just like he did in 1969? For historical or even mere sentimental value, that would be a beautiful idea, I mused.

“Interesting proposition,” he replied tersely, “but not a ghost of a chance.”

In the many conversations I’ve had, on and off camera, with Soyinka, members of his family, his friends and colleagues, acquaintances, readers of his work, and others, his decision to never return to that spot is linked to a number of painful memories connected to those times, the people, the events, and other personal matters.

My decision many years later, after being graciously funded by the Open Society Foundation and Sterling Bank in Nigeria, to produce and direct a short film about that house and its role in Nigeria, the writer and his family, and the University of Ibadan, was inspired both by his response and my own recurring fascination with that encounter and all the histories connected to it.

Maple Grove, Minnesota

Editorial note: Ebrohimie Road: A Museum of Memory will debut in July 2024 in venues in Nigeria, the United Kingdom, and the United States to mark Soyinka’s ninetieth year on earth.