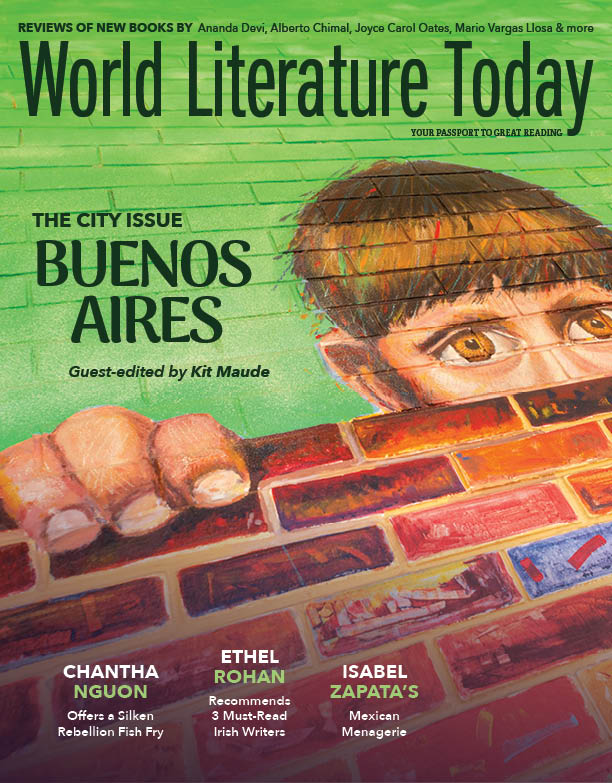

That time I took all the buses in Buenos Aires in order to write a book about taking all the buses in Buenos Aires

Taking all the buses of Buenos Aires, a writer on a mission makes the city his own.

Around 2008 I made the unlikely decision to take all 140-ish bus lines in the city of Buenos Aires and write a book about it, after devouring A. J. Jacobs’s book about reading the entire Encyclopaedia Britannica and seeking a marathon project of my own. I had been gazing at the map of Buenos Aires on our kitchen door and contemplating how little I still knew of the city after ten years here. It is standard for the long-term expat to get to know two or three areas of their adopted city and draw a blank on the rest. I didn’t want to be that guy. I took it upon myself to take all the buses in the city. I took the 1 and the 2. The 3 doesn’t exist anymore. I took the 4, the 5, the 6. I spent half an hour waiting at a bus stop in the back of beyond waiting for the 7. It was cold. It was boring. My best friend’s first son was born, and I wondered where my life had taken this turn.

I gave up. I wrote a novel about a man trying to write a screenplay for a Freddie Mercury biopic who finds Brian May hiding in his cupboard (Freddiementary, still mysteriously unpublished). Clarín newspaper asked me to write an unpaid article for them as a foreigner living in Buenos Aires. I took the opportunity to promote my unpublishable novel and mentioned—only in passing, just one line—that I had once attempted to take all the buses in Buenos Aires. They titled the piece “The Englishman who tried to take all the buses in Buenos Aires.” This, apparently, is how journalism works. Three radio stations interviewed me excitedly about this nonstory. My wife, grimly aware of the economic limitations of my writing, suggested I put Freddie in the cupboard and do something useful, like taking all the buses in Buenos Aires. So I did. It took me seven months.

The excitement of much of the media at the prospect of an Englishman attempting to take all the buses in Buenos Aires always baffled me. It took me some years to work out that it was a combination of their concept of Englishmen—1920s, stiff and umbrella-ed, five o’clock tea-drinking—and their concept of their own buses, more chaotic and dangerous and overcrowded in their minds than in reality. Add to that the oddity that the buses of Buenos Aires occupy a special place in the locals’ (porteños) imagination of what makes them who they are. Sure, a porteño will list food, music, and football among the things that make them who they are, but the colectivos frequently sneak onto the end of that list.

A lot of the buses are individually decorated by their drivers—teddy bear collections, amusing signs in the way that car stickers are considered amusing, an excess of Playboy memorabilia. Many are painstakingly decorated on the exterior in the fileteado porteño style, those swirly colorful lines you might associate with La Boca, often painted by the driver himself, one hand holding his mate while he sorts out your change in one of those change machines, holding on to the wheel with his knee, chatting up the woman in the front seat. Such color is disappearing today as the buses edge toward the uniformity of other cities, but there was still some of it left in 2011, and, most importantly, there was a lot of it in the local popular imagination. Porteños would stop me in the street and empty their popular imaginations into my brain, telling me stories about how the driver used to drive the bus and give you your ticket. And how before that you’d pay the conductor—conductors, Daniel, I bet you never had those in England—and so many more nostalgic recollections about things they held to be unique but were in fact quite commonplace, including the belief that porteños themselves invented buses (they didn’t).

Bus travel here is cheap. At present, at the dog-end of the last Perónist utopia, the average bus ride in the city of Buenos Aires will cost you 59 pesos. To you give you some idea of what else you can buy in the city of Buenos Aires with 59 pesos, you cannot buy anything else in the city of Buenos Aires with 59 pesos. Maybe a potato. Two pieces of gum. A very small box of paper clips. Public transport here has been heavily subsidized for years, and although inflation hit prices for everything else, buses, trains, and the subway stayed cheap. But while forward-thinking countries like Luxembourg, Malta, and Estonia make public transport free for everyone, the Argentine right frowns on such charity and voted in Javier Milei—a short man with a leather jacket and a wig and no evident political expertise—to end our bus-riding paradise. He’s busy dismantling democracy right now, but it’s only a matter of time before bus fares rise to the unsubsidized price of 800 pesos, about 80 US cents (although by the time you read this, inflation and devaluation will have danced their eternal dance once more and those numbers will mean nothing).

To you give you some idea of what else you can buy in the city of Buenos Aires with 59 pesos, you cannot buy anything else in the city of Buenos Aires with 59 pesos. Maybe a potato.

A price of 80 cents per ticket would take the price back to 2011 levels, the time when I took all the buses in the city. Armed with 15 pesos in coins (the securing of which was a constant endeavor), a dumb phone, a bottle of water, and a notebook and pen, I would set off from my Belgrano home at 6 a.m., walk to where the day’s first bus began its route, take that bus to the end of its route, get on another bus there, take that to the end of its route, then get on a third bus, travel to the end of its route and back to where I started, then return on the day’s second bus to where the first bus had left me, and then take that first bus back home. Twelve hours a day, twice a week, just riding buses and looking out of the window and writing down whatever occurred to me. It’s a fine way to write a book.

How did I work out this admirable system for taking all the buses by taking three interconnecting buses per day? Back in 2011, we had none of those apps to tell you how to get about Buenos Aires. We had the Guía “T” (their punctuation). On one side of each of its sixty pages was a section of the map of Buenos Aires, divided into twenty-four squares, numbered A1 to F4. On the opposite page, in boxes numbered A1 to F4, were the numbers of the buses that went through those squares. Then, at the back of the book, there was a list of the buses with their full routes, so you’d find the square you were at and the square you wanted to go to and work out which bus took you there. At this stage you might expect the narrator to say, “It was simpler than it sounds,” but it really wasn’t. You had to get a local to teach you how to use it, and even then it was a few weeks before you really got the hang of it. But once you did get the hang of it, oh man. You felt like you’d cracked the Enigma code. You felt like you were one of them.

There is something strangely satisfying about walking down any street in the city you love and, on seeing any bus, saying to yourself: “Yes. I have taken that bus.”

The book was a flop. Every conceivable news outlet in the country did a piece on me, but people were more interested in el inglés loco than his silly book. But no matter. There is something strangely satisfying about walking down any street in the city you love and, on seeing any bus, saying to yourself: “Yes. I have taken that bus.” But the satisfaction only lasts so long. In the nearly twelve years since I took all the buses in Buenos Aires, I’ve spent eight living away from Buenos Aires. I moved back a few months ago, and, to my very slight horror, I far too frequently find myself gazing at certain buses and wondering when and, indeed, if I ever took them. Not the classic buses like the 106, the 15, the loathsome 55 (Buenos Aires bus joke: you can leave Buenos Aires for eight years and when you come back, the 55 still hasn’t come), but buses like the 99. I saw the 99 the other day, not far from where I now live, and was baffled by its existence. “Plaza de Mayo–Liniers,” it said on the front. I had to look it up in my book. It was one of the last buses I took, at the stage in writing where I didn’t really care anymore about the unique identity of each line and just wanted to finish the whole thing so I could spend my Saturdays on the sofa again. In the chapter on the 99, I wrote about my intense awareness of the 99 bus, that I had seen it every time I went out in the previous seven months. No idea.

People said I was crazy when I said I was going to do this; they called me “El inglés loco de los colectivos,” although do bear in mind that the “crazy” moniker is all too readily applied to much unconventional behavior, without so much as a basic psychiatric evaluation. They said I would get mugged, kidnapped, and murdered in the far-flung suburbs on the south side of the city. Nothing of the sort happened. I took buses through shantytowns. I took buses through neighborhoods that weren’t shantytowns but certainly didn’t invite the casual bus rider to de-bus and explore. I stood waiting in the dirty terminals of Retiro and Liniers an inordinate number of times, the temperature in the nineties, drinking orange juice freshly squeezed at the roadside, eating considerably less fresh sausage sandwiches, contemplating in wonder at how much one man (me) was capable of sweating. I had a great time. A lot of it was intensely boring.

There is one avenue in the geographic center of the city, Avenida Nazca, which has singularly failed to offer literary inspiration in the eighty years of its existence, and whenever I was on a particularly boring bus, it would be sure to turn down this thoroughfare and compound my tedium. But a lot of it was fascinating, life-affirming. There were many moments when I’d go, “Wow, this exists here in this city where I live!” I enjoyed those moments. They were kind of the point of the whole adventure, really. To get to know the place better. And I found that when you get to know a city so much better than you did before, you lose a lot of your fear, your nervousness about that city. You feel even more yourself in it. You make it yours.

Buenos Aires