The Proudest Street in the World: A Brief History of the Buenos Aires Pride March

Each November, Buenos Aires’s Pride march proceeds down a ten-block stretch that is the “spine of Argentine history,” fulfilling Eva Perón’s famous prediction: “I shall return, and I shall be multitudes.”

Madam Eva Perón, measuring almost six foot six, with extraordinary breasts and the obligatory blonde ponytail, hails the crowd. She’s sitting on the hood of a car that has just barely managed to see her through cancer, successive military governments, inflation, and mechanical neglect. The crowd waves back, dancing rather than marching in her wake. She’s not the last travesti in the universe, she’s one among hundreds. What weighs more in this atmosphere, a pound of feathers or a pound of glitter? Which is more scandalous, two women kissing or chants calling for respect for bodies that don’t fit into strict heterosexual pigeonholes? For the passing of a gay marriage law, a law of gender identity and so many more whose ultimate goal is to bring an end to the generalized idea that there are first-class citizens, second-class citizens, and others who don’t even register as existing.

There is a street that appears in all the tour guides of the city. Visitors to the Avenida de Mayo will find, the guides say, lining the street on either side, buildings that reflect the Argentine desire to “pass as European.” Everything around here suggests this is an area where one’s wildest dreams come true: restaurants that look as though they’ve recently been transplanted from Galicia, a building that depicts Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paraiso, inspired as it was by the Divine Comedy. This street has echoes of the Gran Vía and the Champs-Élysées, capped off by an almost genuine French palace.

Everything around here suggests that this is an area where one’s wildest dreams come true.

What you don’t see in the tour guides is the ten-block stretch that begins almost at the end of the city, by the river, and ends at the National Congress building—the spine of Argentine history. Since the nation was founded, forever haunted by the threat of “going under,” the Argentine people have walked and marched and bled and danced along here. It is a shared territory of protest, for the collective expression of joy and hatred. It was the chosen venue for the country’s first ever Pride march.

The crowd, enlivened by the heat, beer, and music, which switches at intervals between ear-splitting techno and earthy cumbia, is naked. They are parading naked but, unlike Andersen’s emperor, are fully aware of that fact. The crowd has chosen to be naked. The Pride march, one of the largest in the world, is held on the first Saturday of November every year in Buenos Aires. But the most impressive part is how its manic aura spreads out afterward, slipping into the homes of the most conservative families, schools, businesses, and even the cathedral that watches it pass by. In Argentina, the first ever LGBTQ Pride march was held on July 3, 1992, clearly inspired by the marches overseas paying tribute to the Stonewall movement. But five years later, in 1997, it was unanimously decided that the march would be moved to November. The reasons were more climatic than political: I’d rather be dead than simple, as the song goes. November is the Argentine spring. What kind of a party, what kind of excesses can you get up to when the thermometer is down around zero?

But the most impressive part is how its manic aura spreads out afterward, slipping into the homes of the most conservative families, schools, and businesses.

Standing with its back to the river is the Casa Rosada, in formal terms the seat of power of the executive branch and, in sentimental terms, the balcony from where General Perón gave his most celebrated speeches and where Eva Perón forged a myth that crossed seas and oceans, as far even as Madonna. This is the balcony where presidents traditionally honor cup-winning football teams. . . . The Plaza de Mayo is below. They say that the best picture to be had is under the pyramid right at the center, a modest monument built to celebrate the revolution that overthrew Spanish rule. It’s certainly an excellent place to appreciate Argentine dignity. It was around this pyramid that the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo began to walk, demanding the return of children who were disappeared during the Dirty War. The mothers were also involved in the first Pride march, offering their support to the brave group of pioneers.

It is also said that November was chosen in order to protect comrades living with HIV from the cold at a time when it was a death sentence. Also, that it was the month of the founding of the first sexual-diversity organization in Argentina and Latin America: Nuestro Mundo (Our World). What everyone agrees on is that the first slogan, as one might expect in this Gallic city, was “Liberty, Equality, Diversity,” and that the crowd numbered no more than three hundred and marched with cardboard masks out of fear of being recognized and losing their jobs.

A travesti Eva Perón waves at another travesti Eva Perón. They share a can of beer and squabble over the chongo passing by on his way to say hello to another travesti Eva Perón a long way ahead of them, almost at the corner of Congress. And so, her famous prediction, pronounced shortly before her death as she urged the Argentine people not to cry for her—“I shall return, and I shall be multitudes”—is fulfilled.

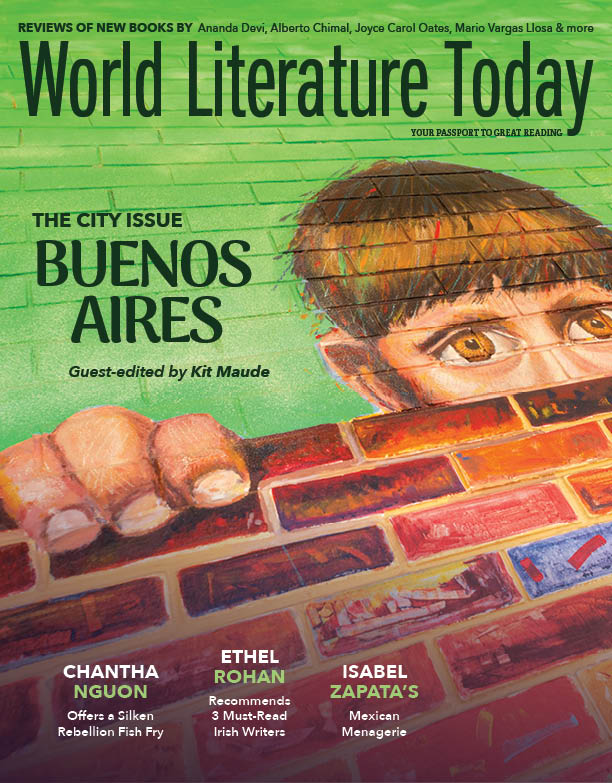

Buenos Aires

Translation from the Spanish