The Struggle of Palestinian Women: Colonization and Feminist Perspectives

In the age of globalization, Western social theories, particularly those articulating the concept of feminism, seem to have taken over the world. Today the women’s movement everywhere is being explained and theorized in terms of gender conflict targeting the patriarchy, irrespective of differences of time and place. Women in advanced industrial societies are said to be facing the same obstacles as women in areas struggling against imperialism, economic disparity, wartime conditions, and alien cultural invasions. Even the UN Decade for Women conferences were premised on the commonality of forces impeding women’s liberation and progress.

In other words, the woman question was to be divorced from the national question in favor of a liberation paradigm that ignored the consequences of international inequality, military occupation, racism, and war. Some experts on the condition of Third World feminine struggles reject the “feminist” label altogether. Viewing this label as the product of overemphasis on an individualistic Western, liberal approach to the female question, several African American writers, like Alice Walker, coined the term “womanist” as an alternative description for a movement dedicated to the survival of an entire people in its female and male sectors. Indeed, the Quran refers to women as the “sisters of men.”

In the view of Cheryl Johnson-Odim, Third World women see a relationship between racism, imperialism, and gender discrimination. These women, therefore, reject Western feminism as being too narrowly defined as a war against gender-based discrimination, when it should address issues of concern to their own national experience. Within their own societies, women, men, and children are victimized by racist regimes and world forces of economic exploitation and control. Johnson-Odim concludes that Third World women achieve their own liberation through political struggles in a manner not dissimilar to the battles fought by Western women during the early part of the twentieth century.

Bell Hooks (aka Gloria Jean Watkins) asserts that Western feminism is undisputedly a white, middle-class ideology focusing primarily on male oppression of women. This ideology views the institution of the family as the instrument of women’s oppression. But to Third World women, the family unit is an indigenous institution that is essential to the survival of men and women. This dichotomy of views led to an open confrontation between Palestinian and US delegates at the UN Nairobi Conference on Women in 1985, when the former group insisted on placing the subject of Palestinian women on the program’s agenda. The subject was finally listed in response to a General Assembly recommendation calling on the planners to note the condition of Palestinian women living under “racist, or colonial rule” in the Occupied Territories. Subsequently, much of the debate at Nairobi turned into a heated argument between the Palestinians and their South African allies on one side, and Western women on the other, over the relevance of pursuing a feminist agenda focused primarily on individual liberation.

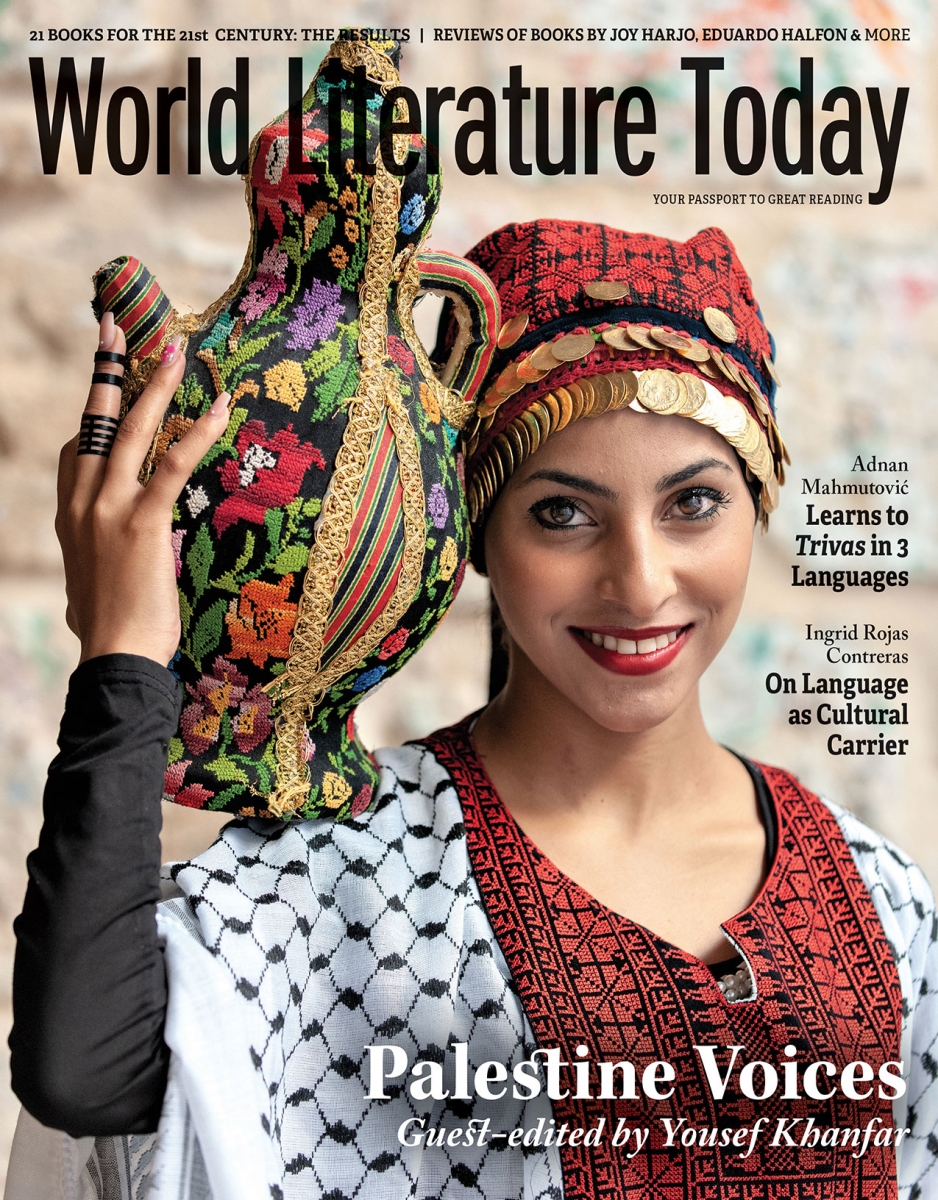

Courtesy the Matson Photograph Collection / Library of Congress

Forging an Identity

Few would question the fact that the identity of Palestinian women was forged in the crucible of war and revolution. Volatile political conditions in post–World War I Palestine led to the inevitable involvement of women in the nation’s political struggle. The first to be mobilized were upper-class and elite women whose male relatives were often heavily involved in the resistance. But as conditions deteriorated and the loss of life and land mounted, political mobilization expanded, eventually reaching peasant women. Massive women’s demonstrations appeared during every national crisis, such as the Wailing Wall Riots of 1929.

The earliest organized national resistance group, the Arab Executive, soon emerged to do battle against the British Mandate Government. There was soon the Arab Women’s Executive Committee, whose participation in demonstrations and acts of resistance were seen as a reflection of the modernist worldview of the male leadership. And the early Women’s Executive, not surprisingly, was made up of Muslim and Christian Palestinian women. Their major duty was to communicate the nationalist version of the Palestinian narrative to other female-affiliated groups. What is even more surprising was the spontaneous participation of peasant women in the demonstrations of the 1936 Arab Revolt.

After the Nakba, the loss of Arab Palestine in 1948, women dedicated their new lives in neighboring Arab countries to publicizing their cause and winning converts. Salwa Abu-Khadra, a Jaffa-based leader, fled to Damascus where she founded the Women’s Union, becoming one of the earliest cadres of Fateh. Similar organizations emerged in Cairo and other Arab capitals. The thrust of these organizations was charitable work benefiting the new Palestinian refugees who were driven out of Palestine in 1948.

When the first PLO under Ahmad Shuqeiry and Egyptian President Nasser’s sponsorship held its first meeting in Jerusalem in 1964, it attracted a female delegation of 45 out of a total male attendance of 422. But in 1965, a new call from the more popular second PLO, later headed by Arafat, led to the emergence of the General Union of Palestinian Women (GUPW) in Gaza as the oldest PLO cadre, preceded only by the General Union of Palestinian students (GUPS), also at Gaza. One of the first members of GUPW was Intissar al-Wazir, or Um Jihad, wife of Khalil al-Wazir, the second powerful leader of Fateh. Now, there was no more emphasis on charitable work, as the second PLO encouraged the latest metamorphosis of organized Palestinian women to visit and establish relations with women’s groups in Cuba, East Germany, the Soviet Union, and Iraq.

But women also sought to play nationalist roles outside the structures of the PLO. The most notable of this group was Samiha Khalil, whose social-welfare institution, In’ash al-Usra (Sustenance of the Family), sought to provide Palestinian women with an alternative to becoming the latest underclass serving the Israeli economy. She also ran in 1966 for president of the Palestinian Territory in opposition to Arafat. This former teacher became a legend in her own lifetime as she grew her organization into an orphanage, a bakery, a nursery school, a library, a folklore museum, and a textile shop as well as a university scholarship program for three hundred female students.

Thus, the case of Palestinian women remains an inseparable part of the Palestinian national narrative.

Lake Forest College

References

Soraya Antonious, “Fighting on Two Fronts: Conversations with Palestinian Women,” in Third World, Second Sex, edited by Miranda Davies (London: Zed Books, 1983).

Alex Fishman, “The Palestinian Woman and the Intifada,” New Outlook (June–July 1989): 9–10.

Ellen Fleishmann, “The Emergence of the Palestinian Women’s Movement, 1929–1939,” Journal of Palestine Studies 29, no. 3 (Spring 2000): 17–31.

Amal Kawar, Daughters of Palestine: Leading Women of the Palestine National Movement (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996), 6.

Gideon Levy, “Samiha Khalil: First Lady,” New Outlook (June–July 1989): 38.

Simona Sharoni, Gender and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995), 59.

Ghada Talhami, “Women under Occupation: The Great Transformation,” in Palestinian Women under Occupation and in the Diaspora, edited by Suha Sabbagh & Ghada Talhami (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Arab Women’s Studies, 1990), 16–18.