Poetry as Field

There is a field. We don’t question its meaning or try to find narrative or accessibility. There is simply a field.

I

It began in the dark. Waters swell and out bursts life from the mist and fog. From the bodies came language that created fire and direction. Language then created worlds, first a second, then a third, and a fourth. Each time, finding a hole in the sky to crawl through into the next. Crawling from the bottom to the top of each world. Time grew from this; not from Point A to Point B, but from the feet to the head. Time doesn’t pass, time builds. Time builds and leads to an open field. We can see the field. We see the plants and maybe a few flowers. Depending on our experience, we may see a stream or river. We may see mountains. The field is both ours and not. There is a field, we know that for sure.

These worlds built with time and language are an act against conquest. Their existence contradicts the existence of conquest. The more they are told, the more they are moving against what is told against us.

II

When I teach poetry to students on my reservation, I often try to find ways to talk about time and image. For example, I ask my students to go to a grocery store and listen to other folks’ conversations. I ask them to listen. A student returned once with a story about a grocery store in Gallup, New Mexico, and she said she heard a woman say, “Tell me what you need because I don’t want to go all the way back to come all the way back.” We talked about the implications of the woman’s language. What did she mean when she said, “I don’t want to go all the way back to come all the way back?” We decided it meant that she didn’t live in Gallup and she didn’t want to return home just to return back to Gallup for additional items for her family. I asked, how could that become a poem? Time, perhaps. The woman was both existing now, in the present, and in the future. Image, perhaps. The woman driving from Gallup back to the reservation would pass through some open fields, rolling hills, glimpses of long sky. Each one, a poem of its own waiting to be written. Just because the woman doesn’t say, “I don’t want go back through the slanted hills of sunset light to come all the way back to streetlamps and cash registers,” doesn’t mean they are not there. Perhaps she doesn’t see them. The function of the poet then is to write a poem that acts like a field on the way home. To remind us that there is a field there, even if we don’t give it language. Poetry becomes the field, bringing function back to art.

III

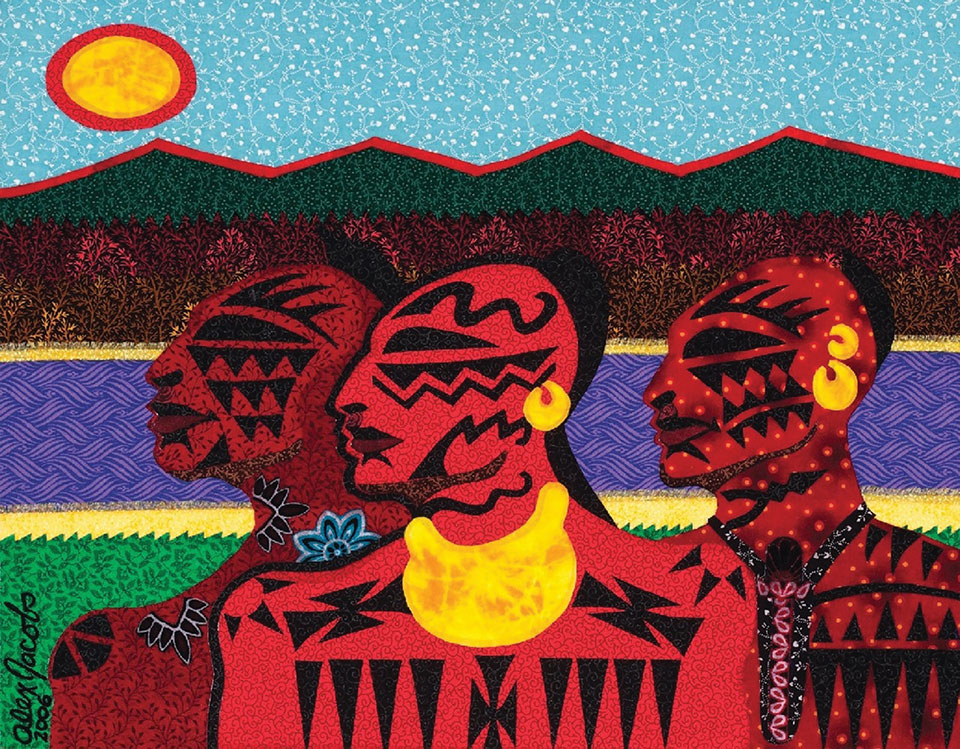

A friend of mine pointed out that he had trouble with the term “Native Art.” He proposed that perhaps there is no such thing as Native Art because art to Diné was not an aesthetic art but a functional one. A beyond art. What we consider Diné art now (rugs, pottery, jewelry, moccasins, etc.) had specific functions in daily life; some still do. I would assume that art from other tribes has a similar purpose. Therefore, what, then, is “Native Art”? Is it something beyond art or does it exist in an entirely different lexicon than aesthetic versus function? What does that mean for poetry?

In the June 2018 issue of Poetry magazine, an issue edited by Heid Erdrich, Tanaya Winder writes, “My art is meant to help heal youth. Teaching writing and poetry comes down to impact—if art is a weapon, we can use it as a shield. Poetry helps us wade through ancestral traumas carried in our blood memory. Poetry reminds us to breathe, that we are magic, and that we are love(d).” Poetry has a function. Winder’s function is stated here. Native literature today is doing so much with function. Tommy Orange brings light to an urban Native experience, Terese Mailhot talks about using language to heal, Tommy Pico opens up poetry to all language, and the list goes on and on. The question remains, is it art? What is art?

There is a field. We don’t question its meaning or try to find narrative or accessibility. There is simply a field.

IV

I use the loom as an exercise for writing poetry. I ask students to think of a place. I then have them look through magazines or a list of assigned words to find words or phrases that speak to the place they envision. I ask them to write a poem using the found words or phrases. Next, I ask them to tear the poem up line by line. I ask them to shuffle the lines around and build the poem from the last line upward to the first. I ask them to read the poem aloud. I ask them to avoid logic and linear time. I ask if the language and poem still speak to and for the place they envisioned. I have yet to hear a poem that hasn’t. Finally, I ask them to choose their best line and, as a class, we write a poem together using their favorite line. One student puts down the last line of the class poem and one-by-one they put down their favorite lines until we have a poem woven with places of the students. We can see and feel them all. The fields of spaces and its energies.

The loom for a Diné rug is a construct of the land and the person’s energy. I helped my partner set up his loom, and I remember pulling and holding things in place while he moved quickly around the loom. Each part of the loom represents an aspect of the physical world, like lightning or the rainbow. Each one holds the rug into place. The loom is, as Barbara Guest discusses, an Invisible Architecture. It is one one can feel. One can feel the energy in the rug. One can feel where the weaver began the rug or where the weaver grew tired. The poem is similar. It is informed by physical landscapes the poet encounters. A reader can read its energies, where the poet began and where the poem begins. Like a rug, a poem tells a story. It has a function with its connection to deep time and ancestral time. It reminds us of things we forgot to see.

There is simply a field. A field beyond meaning. We know there is a field because we see the field. We must continue to see the fields for those of us who drive past them or burn them down. There is a field.

Tsaile, Arizona

by Jake Skeets

I

Horned toad fire-adapts on downed juniper

hymning prayer for dead bushes, yucca plants,

and everything else.

II

My mom sings along to Waylon Jennings

while making tortillas in the kitchen.

She says she doesn’t know how to dance

and asks if she’s pronouncing oppressed correctly.

III

Water is never stolen—it is only given new tongue

one of border, one of lead, one of electricity, one of death.

IV

Auntie, I see the scar on your arm from boarding school.

Skin grafts, vaccination shots, bathroom soap.

Tell us another story, the dough hanging from your hands

crusted with flour and starlight. Tell us why we stay quiet

when the lightning and thunder come.

V

An ephemeral lake returns—placid silver, ankle-deep.

Frogs sing at night, drowning the rains.

Author note: Samuel Black, Diné, asked me about the function of art and brought up the existence of art. I think it was an excellent question and one I will continue to ponder. The quote from Tanaya Winder is borrowed from her essay “Words as Seeds” in the June 2018 issue of Poetry. I want to acknowledge my partner Quanah Yazzie and colleague and friend Orlando White for their insights into the loom and poetics. I want to acknowledge Sherwin Bitsui’s lecture on the Field / Poem and Charles Olson’s “Projective Verse” because they added to my understanding of Field.