Lilliam Rivera’s Orpheus and Eurydice Remix: Talking about Never Look(ing) Back

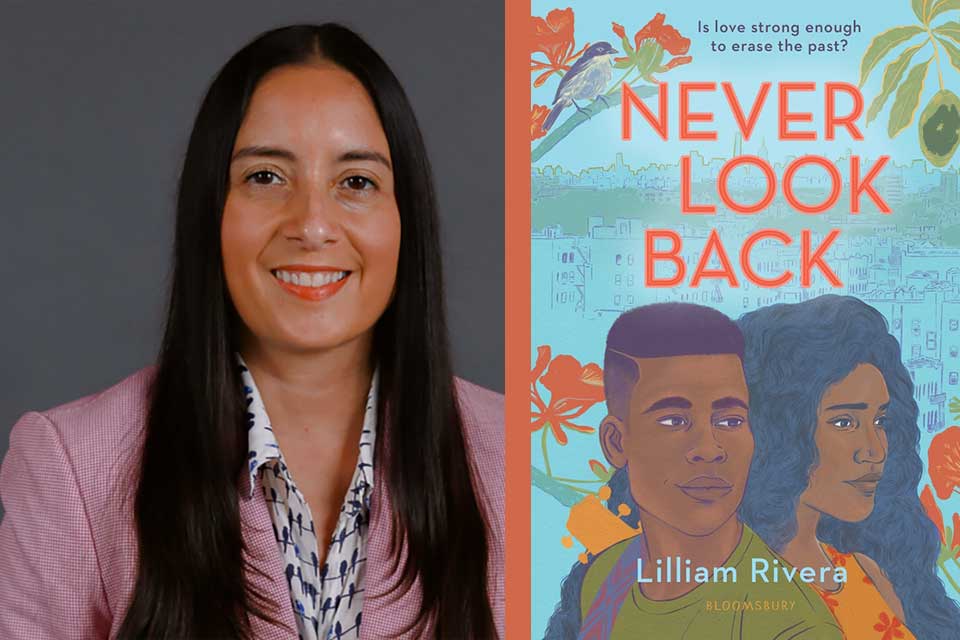

Lilliam Rivera is an award-winning author of children’s books who currently resides in Los Angeles, California. Rivera’s work has appeared in the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, and elsewhere. Rivera’s latest novel, Never Look Back (Bloomsbury, 2020), retells the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, set in New York and influenced by various elements of Latin culture. I sat down with Rivera to discuss this novel, its influences, and Lilliam’s personal efforts and experiences as she wrote.

Bayleigh Acosta: So, this story retells the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice from a Latinx perspective. How did this connection come to life? Have you previously used Greek or other myths/cultures as inspiration for writing?

Lilliam Rivera: I’ve written short stories maybe that incorporate mythology from Caribbean mythology or folktales, and such like that, but I’ve never written a whole book that’s a retelling, so this was my first vehicle into doing it, and the Orpheus and Eurydice story was a myth that I really loved when I was young. I kind of fell in love with it. I watched this movie called Black Orpheus, which is a classic 1950s film, that’s a retelling of the myth set in Brazil during Carnival. I just love that movie so much, and I was just trying to figure out what I wanted to write, and I was like, “How can I rewrite this story and be able to incorporate Caribbean mythology, and maybe Taino mythology a little bit, and tell a story that’s still about love and about tragedy?” And all of the other things that you find in mythology, but make it my own. You know, make the story the type of story that I would want to read. It was fun, it was hard, but it was good.

I was feeling hopeless because Hurricane Maria happened. It was literally because I needed to write toward hope; I needed to write toward love.

Acosta: Yeah, I mean, the love connection is obviously a big part of the retelling. But there are also other messages about trauma, and culture, and mental health. Why do you think the “love” in particular is so significant to this retelling?

Rivera: Well, that was just simply a selfish reason, because I was actually going through a depression. I was feeling hopeless because Hurricane Maria happened, and it affected my family in Puerto Rico and in New York, which is where I’m from, and then I was really feeling hopeless. I didn’t know how to write—or I couldn’t figure out what to write next, because everything I wrote was really dark. So, that’s when I came up with the idea: if I use this structure, then I know the story itself, and maybe if I use the structure it’ll help me write a novel. It was literally because I needed to write toward hope; I needed to write toward love. I used that structure and the Orpheus myth to help me keep it in one stop, so I wouldn’t veer into anything else. I used love because I needed love, and I’m sure everybody needs love.

Acosta: Yeah, and I love how it came out around this time, with the pandemic and everything. I’m sure that only added to everything else that was going on.

Rivera: Yeah! Who knew that we would be longing to hug and kiss people? Who knew that that would be the thing we crave the most? When I was writing it, at the time, I wasn’t thinking about any of that. I was just thinking about how these two young people will survive, you know?

Acosta: Definitely. And then, the religion throughout the story—that recurring theme. Do you think that comes from the Latinx cultural values on religion, or more so as an alternative to mental health therapy; where do you think the religious aspects fit in, mostly?

Rivera: I mean, I had written an article specifically about Latinas suffering from mental health, and suicidal rates are really high for Latinas, specifically young Latinas. I had written that a while ago—I think in 2015. I was always so surprised, not surprised in a sense because it made sense, but surprised how high the rates were. Because the community comes from this mentality of “you’re not supposed to air out your problems,” and maybe “leaning into faith” is what you should be doing. I grew up as a Catholic, and that was totally the case. Like, no one talks about seeking any kind of mental health professional help at all. It’s more like, you know, “maybe you need to work harder,” “maybe you need to stop drinking as much,” “maybe you need to pray.”

And I wanted to talk about that, and be able to bring that up in conversation in my book because there shouldn’t be any stigma when it comes to asking for help. So, you could pray, and be religious, and seek professional mental help and therapy. You just carve yourself your own way of dealing, which is what I do. I want to be able to talk about that because I don’t think it’s something that our community talks enough about.

Acosta: I definitely agree, even just from my own personal experiences. Because this story is primarily centered around Eury and her personal battles and those mental health struggles, do you think the message would change a lot if it were instead centered around Pheus—perhaps in a different context? What comes to mind for me, also, is the “machismo” in Latin culture and maybe how that affects young men like Pheus.

Rivera: Yeah, I mean, Pheus is interesting because his father is unique. He’s not very machismo, in a way. He’s lost, we know that he’s pining for his ex-wife, and maybe he doesn’t have a steady job. But what I love about his relationship with Pheus is that he’s like: “Don’t accept anything.” And he has tools that he can use like books, and articles, and thinking outside of what they’re told. I really believe that if it was Pheus-focused, his father would have given him a lot more insight as to how to take care of himself.

And the great thing about Pheus is that you see his arc, and his journey as to how he goes from a person who is a nonbeliever and becomes a believer. I always feel like he was the type of person who would say, “Oh, I don’t believe in any of those things,” or “I don’t believe in ghosts.” Maybe he believed in mental health, but like he didn’t believe in anything that was outside of what he could see. And that’s what I love, that maybe he developed more religion or leans more into faith—which I think is great. It should be a balance of both, I feel.

But I really did want to make sure that the focus was always on Eury, because if you read the original retellings of the story, it’s always been on Orpheus. It’s always about him saving the day, or him trying to save the day and failing, but I really wanted to put the focus on her. Because, you know, they don’t save each other—they have to save themselves first, and find each other.

I really did want to make sure that the focus was always on Eury, because if you read the original retellings of the story, it’s always been on Orpheus.

Acosta: Exactly! I love that. And, looking back at part 2 of the book, when the demons and spirits come into play a little more, where did that inspiration come from? I mean, they have a very distinct characterization and detail.

Rivera: I was just really digging into the Caribbean history and Carnival, and the way the Caribbean—Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic—celebrate festivals. I really wanted that to be significant. I wanted this building, the King’s Bridge Armory, which exists in the Bronx and is empty—they keep saying they’re going to make something out of it, like a sports arena and all of this different stuff—it’s a huge building. I read about the history of that building. That building used to be owned by the army, it used to be for military practice. And then, it used to be a boxing ring. All of these weird uses, but everything tied to violence.

So I thought, even if a building is empty, all these spirits and all the fingerprints of what it used to be like still live in the building. That’s how I imagined what El Inframundo would look like; it would be something that looks similar, but a little bit skewed. The demons, and the piglets, and all of those things that I used to create the Inframundo world really just feed off of whoever enters. With Pheus, because he’s Dominican, that’s what his fear is. His fear revolves around bachata music and not wanting to be a singer, or wanting to be a singer and being seduced by it, but not wanting to be seduced. That’s his fear, and it rises up when he ends up having to entertain the people who rule that area. It was fun for me to write it; I could’ve written way more in that world.

Acosta: Yeah, and going off of that—the music being so present throughout the novel. I know that it is also present in the original myth too, but how did you go about changing it or selecting the specific songs? Did that have influences from your own life, or was it something you had researched?

Rivera: No, it was all research, for the most part. I mean, I had a little bit of knowledge of bachata music. But, because it’s Pheus and he’s Dominican, I really dug into the history of bachata music, and it felt like a “rooted” music, kind of like country music to me. Then I really was like, “Oh, Santos is a really big name right now.” And, he’s from the Bronx and he’s Dominican, which is fascinating. He’s like the big-time name of bachata music.

But then you start looking into the history of the people who created it, and so that was fun to be able to inject all those songs in there. Like, honestly, when I first wrote it I wrote in all of these verses from the songs and I had to take them out because you have to pay royalties for that. I just fell into the music way more—it’s super fun and I love it so much. It’s so sexy, and the dancing is great.

Acosta: Definitely, I thought that was one of the best parts of it; seeing all the specific songs and knowing that I could search up that song and listen to it. I really enjoyed the story and how it was able to connect this myth, which seems like it’s from a totally different culture, with this culture. Do you hope to continue with similar retellings in the future?

Rivera: I mean, I don’t have any other retellings. But I feel like in a lot of my stories, when they combine speculative stuff like demons, or ghosts, or what-have-you, they’re really a remake of things that I’ve seen or read from when I was young. My next novel will be a remake in a sense that I’m looking at science-fiction books that I’ve read before, like Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov. You know, things I used to do when I was a nerd. I really loved reading those kinds of books.

I’m reading those and just trying to find my Brown and Black characters, and how they would relate to these things that happen to characters they write about who are white. I’m like, “We would relate to it differently.” Whatever that would look like, it would be different to a person of color. Those are my kind of remakes, but I don’t have a retelling in the mix. If I did, it would probably be Frankenstein.

Acosta: Oh, really?

Rivera: Yeah, it’s one of my favorite books, but I don’t know what that would look like—that’s why I haven’t written it. But if I were to do another retelling, it would probably be a Frankenstein retelling.

Acosta: That’s super cool! Obviously, the commentary on mental health, especially among young Latinas, was significant. Do you think you’ll revisit that theme in the future?

Rivera: I’m not sure. Sometimes, for me personally, when I write I don’t think of it as tackling a certain theme. I just write a story and then realize, months after I’ve written several drafts or revisions of it, that I’m writing about my depression, or I’m writing about an abusive relationship. These are things that I don’t realize I’m going to write about, so strangely I never come in with an agenda. I just decide to tell a story and then later on, when I’m digging into the rewrite, I’m like, “Oh, that’s why this is taking a lot—physically and emotionally.” Because I’m writing about an abusive relationship or I’m writing about addiction. All these things that are personal, and I never know how it’s going to come out in my stories, so it just pops up. I don’t know what my next book is about—it’ll probably pop up later.

Acosta: Yeah, and I feel like that only adds to the authenticity—you know, taking the hurricanes and people from your surroundings. Do you draw a lot of inspiration from current events, most of the time?

Rivera: Yeah, I wonder, “How do I write about feeling hopeless or angry?” I have to find a way of writing about it through fiction, because that’s really the way I tackle things. My go-to is to write a story and hopefully write toward hope, because if not it’s just going to be really dark. They would just stay in El Inframundo forever. (Laughs) But sometimes you just have to write dark stuff.

Acosta: I thought it was so interesting, again, how the book connected with familiar experiences for me, as a Latina, just right off the bat.

Rivera: I’m so grateful that you were made aware of it, that too is a blessing. And, I wanted to tell you that there’s a playlist—you can listen to the music! It’s on Spotify, through Bloomsbury, but if you look up “Never Look Back,” you’ll find it, and it has all the songs on there.

Acosta: Wow! That’s awesome, I’m definitely about to search that up.

Rivera: Yeah, it’s a good playlist, I was definitely listening to it all the time as I was writing . . .

November 2020

A Review of Never Look Back, by Lilliam Rivera

by Bayleigh Acosta

Lilliam Rivera’s Never Look Back (Bloomsbury YA, 2020) explores the significance of love and friendship through a retelling of the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Rivera fuses elements of the original myth with Latinx cultural values to create a story of trauma, love, and eventual peace. Set in modern times, the main characters, Pheus and Eury, experience relevant issues—from the hurricanes in Puerto Rico to watching President Trump speak on television. This novel invites fantasy into the familiar world, with the presence of spirits, demons, and El Inframundo (the Underworld). The book is divided into two parts; the first following Pheus and Eury’s journey toward love and trust, and the second illustrating the spiritual trials the two encounter while strengthening and sustaining their relationship. Rivera articulates issues relating to mental health and well-being through a story of romance, magic, and adventure.

Lilliam Rivera’s Never Look Back (Bloomsbury YA, 2020) explores the significance of love and friendship through a retelling of the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice. Rivera fuses elements of the original myth with Latinx cultural values to create a story of trauma, love, and eventual peace. Set in modern times, the main characters, Pheus and Eury, experience relevant issues—from the hurricanes in Puerto Rico to watching President Trump speak on television. This novel invites fantasy into the familiar world, with the presence of spirits, demons, and El Inframundo (the Underworld). The book is divided into two parts; the first following Pheus and Eury’s journey toward love and trust, and the second illustrating the spiritual trials the two encounter while strengthening and sustaining their relationship. Rivera articulates issues relating to mental health and well-being through a story of romance, magic, and adventure.

Rivera carefully manipulates the original Greek myth to reflect a multitude of shared experiences in life as a young adult, especially as a Latinx young adult. Pheus and his struggles, whether it be in his romantic relationships or his budding career as a musician, are relevant and relatable. Young men and women alike can recognize themselves in his character; the same individuals can even see themselves in Eury as well. Eury battles trauma and resulting mental health issues, all the while experiencing young love and familial strife. Latinx culture and religion follow alongside Eury and Pheus’s journey, until each of these elements begins to intertwine with the other—creating a cohesive and healing tale.

While there is no included background information on the original Orpheus and Eurydice myth, the retelling is not difficult to follow. The fantasy elements of this story happen rather suddenly but are an inciting factor within a journey of love. The chemistry between Pheus and Eury is evident almost immediately, but the tension created by an added third party creates a sense of momentum—especially considering that this third party is a spiritual entity. Eury faces the challenge of accepting love in her reality while confronting the demons in her mind. It is easy to appreciate the basics of the love story between Pheus and Eury throughout, but the addition of fantasy, mythology, and spirituality elevate the narrative, allowing for an even larger audience to enjoy the novel.

As a Latina woman, I found this story to be both inviting and encouraging. Almost immediately, the familiar aspects of Latinx culture curated a comfortable environment. Throughout my read, I was able to recognize myself in each character and their actions; the alternating perspectives, changing from Eury’s to Pheus’s point of view with each chapter, allow for any young adult to visualize themselves in the novel. Rivera successfully communicates elements of the human experience, such as love and adventure, that will resonate with many.