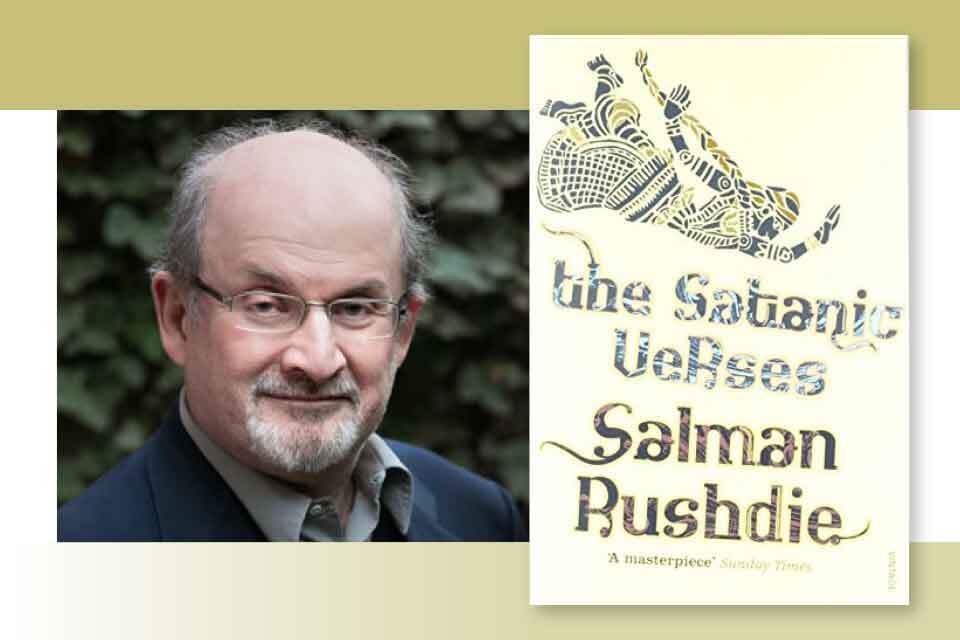

Salman Rushdie and the Freedom to Offend

Reflecting on the recent attack on Salman Rushdie, Andrew Martino asks, “What does the attack on Rushdie tell us about ourselves, about our relationship to literature and writers?”

Like most of the world, I was shocked and saddened to hear about the savage attack against Salman Rushdie on a stage in upstate New York on August 12, 2022. I suspect that most had either forgotten about the fatwa on Rushdie or considered it an empty threat by now. Others would not have known about it at all. Cultural memory is short, but the memory of hate and intolerance, to say nothing of the price still on Rushdie’s head, is long, and it seemed to finally catch up to him.

One of the most disturbing facts is that Rushdie was brutally attacked in twenty-first-century America twenty-three years after Iran “lifted” the fatwa in a show of good faith toward Great Britain. The young man who attempted to assassinate Rushdie traveled from New Jersey. It is unclear at the time of this writing what his motive might have been, but he has pled not guilty. Perhaps this young man was offended by The Satanic Verses, or perhaps he was fulfilling what he believed to be a call for all Muslims to assassinate Rushdie. I am willing to bet that he has not read any of Rushdie’s work. And does the motive really matter?

Long before the events of August 12, 2022, Iran’s spiritual and political leader, Ayatollah Khomeini, issued a fatwa, or legal decree, calling for the assassination of Salman Rushdie on account of his “blasphemous” novel The Satanic Verses. Immediately, word got out (February 14, 1989, to be exact), and soon Rushdie was forced to go into hiding under the protective custody of the SIS of the United Kingdom and a branch of the Metropolitan Police. For a decade Rushdie was forced to hide, to go into the shadows, sometimes changing beds and safehouses each night. It must be stated that Khomeini admitted to never having read the novel but was informed of its blasphemous content (this narrative sounds familiar). In an essay collected in his 2002 collection of nonfiction, Step Across This Line, Rushdie writes, “Sometimes I stayed in comfortable houses. Sometimes I had no more than a small room in which I could not approach the window lest I be seen from below. Sometimes I was able to get out a bit. At other times I had trouble doing so.” We are not talking about a political prisoner but a writer, a public intellectual who wrote a work of fiction in the late twentieth century. And yet the loudest voices in Tehran not only condemned his right to free speech but condemned him to death because of what he wrote. Rushdie examines his life under the fatwa in his 2012 memoir, Joseph Anton, but in the third person, as if detached from the events.

To uncover the possible blasphemy of The Satanic Verses at a surface level, one need only examine the chapter entitled “Mahound,” which details the reworking of certain Suras of the Qur’an and the inclusion of parts as recited to Mahound (Mohammad) by the Devil, and not Allah. “This is what he heard in his listening, that he has been tricked, that the Devil came to him in the guise of the archangel, so that the verses he memorized, the ones he recited in the poetry tent, were not the real thing but its diabolic opposite, not godly, but satanic.” Thus the novel’s title.

The most important tenet of Islam is the following: “There is no god but God, and Mohammed is his prophet.” Equally important is the belief that the Qur’an is the literal word of God, conveyed by him through Mohammed and recited by the prophet to be taken down by scribes. The belief that there is no other god but Allah, and Mohammad is his prophet, combined with the absolute belief that the Qur’an is the word of Allah, may seem like more than one tenet, but like the Holy Trinity in Christianity, we cannot separate the three from the whole (Allah, Mohammad, the Qur’an). Whether we are speaking about the Qur’an or the Judeo-Christian Bible, the suspension of disbelief that we agree to in fiction does not figure into the equation here. In fact, by its very definition, faith demands that the believer believe in the unbelievable without any semblance of proof. The role of the prophet, then, be he Mohammad or Jesus, is to serve as a mouthpiece for God and as a path toward everlasting life. Rushdie’s offense, if we can call it that, was to throw suspicion on the legitimacy of religion (Islam, to be specific) as the grand narrative. “The opposite of faith,” writes Rushdie in The Satanic Verses, is “not disbelief, but doubt.” A fundamentalist interpretation of religion presents us with a closed form of society, promoting an “authoritative” meaning of life. There is no room for doubt or doubters.

A fundamentalist interpretation of religion presents us with a closed form of society, promoting an “authoritative” meaning of life.

I suggest that the real transgression in The Satanic Verses is Rushdie’s portrayal of a new, multicultural, and secular world as inevitably replacing the old religious one. The Devil in the novel is multiculturalism imagined and personified: the exile, the migrant, the unhomed, the stranger. The stranger presents a direct threat to the solid, fixed world of tradition and identity as constructed by the grand narratives of religion and progress. The Devil also takes the shape, at least for this reader, of Mohammed and Jesus, prophets of an absent and angry God. If the novel offends you, then don’t read it! The nature of the offense isn’t personal. Those who take offense do so through the willingness, the need, to make the offending document about them, not about the work itself. Transferring one’s offended sensibility into the universal, one begins to dictate the nature of the offense. It may be helpful to recall Kwame Anthony Appiah’s wise words in his 2006 study, Cosmopolitanism: “Universalism without toleration, it’s clear, turns easily to murder.” And it was attempted murder we witnessed on August 12.

Rushdie is a writer who has always written about movement, margins, about the power of story determined by its migration across cultures.

I do not wish to dwell solely over the novel that caused Rushdie to go into hiding, because Rushdie the writer, the public intellectual, is much more than that one novel. Rushdie is a writer who has always written about movement, margins, about the power of story determined by its migration across cultures.

The bigger question, at least for me, is, What does the attack on Salman Rushdie tell us about ourselves, about our relationship to literature and writers? It is hard to comprehend the polarizing atmosphere of our time despite being confronted with it daily. Many Americans have embraced an illogical and faulty relationship with the truth. The United States teeters on the verge of becoming a theocracy no different from the Iran of the ayatollahs. Censorship is alive and well in twenty-first-century America, and it’s not only coming from the right and its strain of intolerance but also from the left under the self-righteous guise of the super woke and cancel culture. Writers, even those long dead, are being taken from the shelves and reevaluated through the standards by which we live today. We have become, and have been for some time, a society of wimps, unable to rise above hurt feelings and perceived injustices. As Stefan Collini has remarked, “Although feelings are central to the experience of being offended, there is usually also some element of conviction that such a reaction is legitimate or justified.”

What does the attack on Salman Rushdie tell us about ourselves, about our relationship to literature and writers?

Writers are first and foremost storytellers, dreamers who dream whole worlds for us to slip into. Rushdie is one of the most imaginative writers writing today. We must look past the “man who wrote The Satanic Verses” and the narratives surrounding its reception and look deeper into his work, as Randy Boyagoda argued recently in the Atlantic. Boyagoda invites us to start with 1999’s The Ground Beneath Her Feet. I would like to suggest readers unfamiliar with Rushdie start with The Moor’s Last Sigh, published in 1995. Of course, there is always Midnight’s Children.

Make no mistake: the attack on Salman Rushdie is an attack on the freedom of artistic expression. Writers, comedians, musicians, actors, and the like are increasingly being asked to self-censor at the risk of offending people. No, not asking, demanding. This new strain of the culture wars threatens every form of free speech, and the right and the left are each aggressively fighting to outdo one another. Literature, to speak only of my subject here, cannot be beholden to self-censorship and identity politics because too much is at stake. When we begin to engage in censorship, we begin to build boundaries around thinking itself. Literature should be boundless, wondrous, engaging, and, yes, at times controversial. Salman Rushdie has spent his entire writing career examining the boundaries, and he has brought his readers to some of the most magical places beyond this world. Rushdie’s often quoted phrase, “What is the freedom of expression? Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist,” has become more relevant than ever.

If we celebrate Salman Rushdie today, let it not be for surviving a fatwa and an assassination attempt more than thirty years later, as heroic as those are. Instead, let’s celebrate him for the worlds he has opened for us, for the beguiling spells adrift on his sea of stories, for his wondrous tales, for his precision in language and his vision for a better future. But perhaps most of all, we should celebrate Salman Rushdie for daring, after all this time, to speak the truth to power by standing up for free speech, despite the threats made against him. Rushdie’s work with PEN America has been extraordinarily fruitful, to the point of breathing new life into the organization. And despite Rushdie’s guilty pleasure at being a celebrity, he is the epitome of the serious and playful cosmopolitan writer in contemporary literature.

In his essay on India, the first country to ban The Satanic Verses, titled “A Dream of Glorious Return,” Rushdie writes: “You can measure love by the size of the hole it leaves behind.” News has now reached us that Salman Rushdie will survive this attack. But will we?

Salisbury University