The Odyssey of the Tehran Children: Mikhal Dekel’s Story of Holocaust Survival

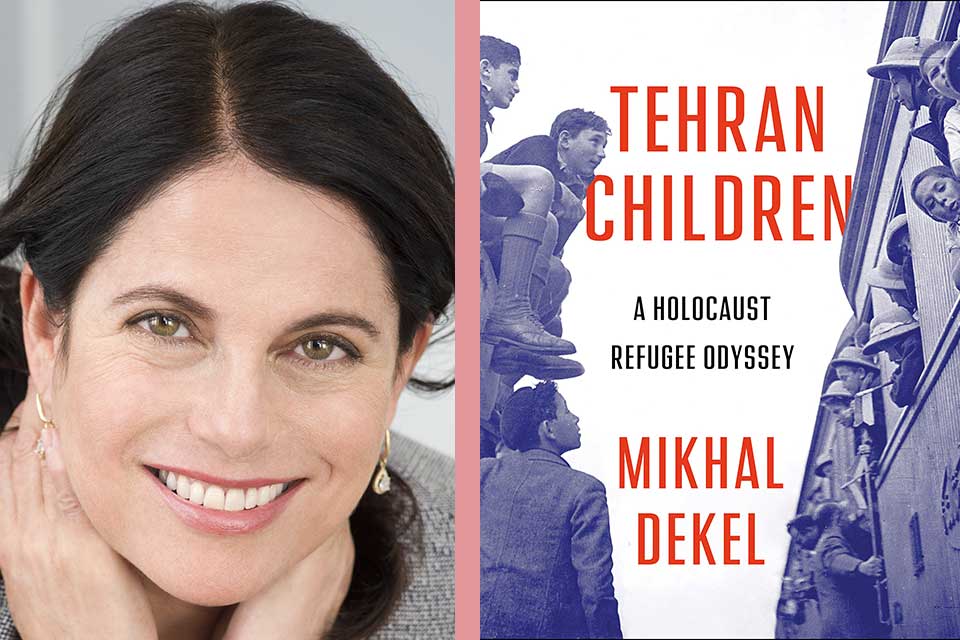

Tehran Children: A Holocaust Refugee Odyssey (Norton, 2019), Mikhal Dekel’s outstanding book, is many things: a memoir, a family genealogy, a history of nationalisms, and an exploration of identity. We accompany the author as she researches and tracks her father’s experience as one of the Tehran Children. This group of over eight hundred Jewish children had been evacuated to Uzbekistan in the interior Soviet Union with thousands of other Polish citizens as part of a Polish-Soviet agreement in 1941. From there a smaller group, including the Jewish children, eventually went from Uzbekistan to Tehran, where they lived for an extended period of time before Zionist activists brought them to live as part of the Jewish community in British Mandatory Palestine in 1943. The author’s father, Hannan Dekel, was born Hannania Tejtel in Ostrów, Poland, to a prominent and respected Jewish family. In September 1939, just before the Nazis arrived in Ostrów, the Teitl family “packed what they could into two Chevrolet trucks and left behind what had been built over eight generations.” From that point on, the author explains, “they became migrants, tiny particles in the huge tide of refugees that swelled Poland’s roads by foot, cart, wagon, car, and truck.” Dekel’s book painstakingly brings to life the Teitl family’s yearslong, horrific struggle as refugees, as the war’s circumstances force them further and further from their prewar home.

The fact that Hannan was a Tehran Child was something that Dekel had always known. But growing up in Israel, this part of her father’s biography had been presented to the author as an uncomplicated Zionist heroic saga, and she had little reason or inclination to challenge that depiction. It was only at a much later stage in the author’s life, after she had herself migrated—under very different circumstances from her father—living away from Israel and happily settled in New York, that she came to understand that her father’s experience as a one of the Tehran Children was far more painful than what she been taught. It is significant that the person who piques the adult Dekel’s interest in the Tehran Children is an Iranian colleague in New York, Salar Addoh. When, in an early encounter, she casually mentions that her father had passed through Tehran on his way to Israel, Salar makes Mikhal aware for the first time that this story is an important one. Her book grew out of this encounter, and from there it unfolds.

Tehran Children is a notable example of the stories that it is possible to find in places where we may have thought there were none. Dekel makes it clear that this is no small endeavor. We see in her book evidence of years of painstaking research that is up against the barriers of language, culture, and distance. Under the author’s care, Hannan and his family do not remain “tiny particles in the huge tide.” They are human beings whose full, extraordinary lives we are able to see. No less important, Tehran Children is a testament to the herculean efforts of people across the globe to save human beings and the incalculable value of their work. Dekel carefully documents the work of countless individuals: members of international Jewish relief organizations who used every possible channel at their disposal under the impossibly difficult conditions of wartime to try to get medicine, food, and clothes to strangers in need on the other side of the world; local Jews from the community in Tehran who brought the sick, emaciated children into their own homes to give them care; young Zionist emissaries who put their own lives at risk by traveling to Tehran to accompany the children on the dangerous journey to Palestine.

Tehran Children is a testament to the herculean efforts of people across the globe to save human beings and the incalculable value of their work.

I finished this book wanting more. I wanted to know more about Hannan as an adult. I wanted to know more about his relationships in Israel, after the war, particularly with his daughter Mikhal, his wife, and his own mother. The author makes it clear that there were tensions in her family home, “that dark apartment” where she and her two siblings lived with their parents and their grandmother for many years: “There were always two teams,” Dekel explains. Her father and grandmother were on one team, while her mother “and us children” were on the other. I wanted to better understand these tensions. I wanted to see pictures of Hannan as Mikhal described him—as a hardened, aged Israeli—to add to the marvelous images she shared: of her father as a child, transformed from Poland through Tehran and then as a teenager in Israel. And I was eager to see photographs from the various stops on Mikhal’s own trip as she traced her father’s long journey, looking for signs of his experiences in the much-changed twenty-first-century landscape.

The book is a poignant and important personal and global history.

Yet despite my own greediness, I am glad that Dekel did not, in fact, give us more than she did. I wanted more because of the sensitivity and honesty that came through in Dekel’s storytelling. This drew me in and made me feel invested in her family. But this book is not a tell-all about her father to sensationalize his private life. It is a poignant and important personal and global history. It is evidence of the many ways that systems of oppression, and the people fueling those systems, can destroy innocent and precious lives. It is also evidence of the power of perseverance, dedication, and love. And what she has given us is more than enough.

University of Oklahoma