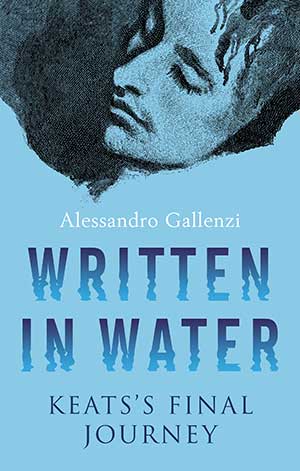

Written in Water: Keats’s Final Journey by Alessandro Gallenzi

London. Alma Books. 2022. 358 pages.

London. Alma Books. 2022. 358 pages.

Is there anything authentically new to add to the already well-known story of the Romantic poet John Keats’s heartbreaking final days? Alessandro Gallenzi thought there was and has broken Keats’s final few months down into a moment-by-moment tableau that has the feel of the “slow time” in the poet’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” What emerges are some familiar echoes but also some new information.

Keats’s journey from London to Naples took two months, yet biographers have largely passed over this interval to focus on the time afterward that Keats spent dying in his tiny room on the Spanish Steps in Rome under the attentive care of his physician, Dr. Clark, and his devoted friend, the painter Joseph Severn. What Gallenzi has done is to instead focus on the time Keats and Severn spent beforehand at sea onboard the Maria Crowther and especially on the period that followed when they were released from quarantine and disembarked in Naples. The shift is a fruitful one, for it reveals fresh facts.

One is that the consumptive Maria Cotterell, who accompanied Keats on ship, had a prosperous merchant brother with literary interests waiting for her in Naples, Charles Cotterell, who was to play a significant role in Keats’s time in Italy and on into his afterlife. Cotterell was heroically generous in helping Keats and Severn to recover from their ordeal at sea—where they had endured recurring periods of illness and perilous storms—by finding them suitable lodgings and arranging for them to attend cultural events like the opera. He also helped them find the safest, most efficient passage from Naples to Rome, which was difficult in the nineteenth century because of the primitive condition of the roads and the dangers posed by thieves and criminals along the way.

After Keats died, Cotterell more than once hosted the still-grieving Severn at his home in Naples, the scene of literary salons that included no less a guest than Charles Dickens. Gallenzi feels that the story of Cotterell’s role in Keats’s life is still evolving and tantalizingly suggests that documents shedding further light on his interactions with Keats and Severn are likely to yet appear.

The posthumous shaping of the poet’s biography also comes under Gallenzi’s scrutiny. He declares that many of the often-repeated stories about Keats’s final days never actually happened and that such distortions occurred largely because biographers tended to rely on two particular chapters in William Sharp’s The Life and Letters of Joseph Severn. Yet Sharp’s representation of Keats, Gallenzi argues, is consistently misleading, stressing, for instance, the poet’s carefree nature and witty exuberance through the time of his death, which in no way resembles Keats’s actual gloom and bitterness as he felt his life slipping away. Gallenzi demythologizes a number of other distortions, asserting that whenever Sharp encountered an area of missing information in Keats’s life story, he simply fabricated a scenario that was upbeat or picturesque, such as Keats’s joy on first catching sight of the city of Naples from his ship—when no firsthand account of this moment actually exists—or Shelley’s pressing Keats to stay with him and Mary at their home in Pisa while in Italy, when in fact Shelley did not even know Keats was in Italy.

Stories like these will make readers come away from this latest chronicle of Keats’s final journey feeling that it deserves more meaningful illumination and research.

Rita Signorelli-Pappas

Greensboro, North Carolina