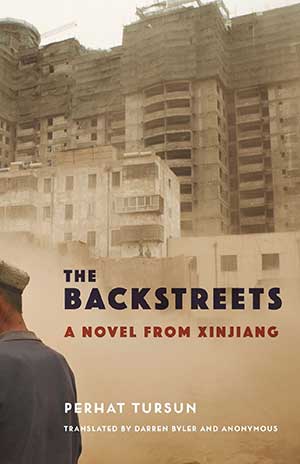

The Backstreets: A Novel from Xinjiang by Perhat Tursun

New York. Columbia University Press. 2022. 168 pages.

New York. Columbia University Press. 2022. 168 pages.

The first novel of its kind to have escaped suppression, The Backstreets is a harrowing vision of the experience of the Uyghurs, an ethnic group systematically marginalized and abused by the Chinese authorities since 2014, written by an important Uyghur novelist who was himself arrested and sent to Xinjiang’s internment camps. Its dense, disjointed narrative of a young man lost within a fog-bound city trying to find a room to stay in is both a political allegory of displacement and alienation and a physical evocation of being an outsider in a radically defamiliarized, hostile urban space in which the protagonist has no bearings and no sense of belonging to. The novel’s prose, equally, enacts the endless circuitous quest of the narrator by going nowhere, circling in on itself without any scaffold of chapters or sections and ostensibly without the road map of plot progression, character development, or dramatic suspense, reiterating one key sentence every few pages (“I don’t know anyone in this strange city, so it’s impossible for me to be friends or enemies with anyone”) like the haunting refrain of a ballad or old song.

As such, The Backstreets is an antinovel that foregrounds its contrast to the complacencies of Western middlebrow fiction, invariably built on First World assumptions of social, financial, and housing stability, the universality of which Uyghur experience refutes. Perhat Tursun—a widely read student of world literature and philosophy before his disappearance—repurposes here the existentialist prose of Camus and Sartre, the novel’s deracinated protagonist questioning his very being within the endless, polluted smog of Urumchi:

Who had I been, what was I, and who was I going to be? Suddenly I felt that no matter how hard I tried, it was impossible to remember. Not only did I not even know who I was, but I also didn’t know what role I was playing now. My consciousness was gradually fading.

The great precursor of existential dread and absurdism, Franz Kafka, also comes to mind in the protagonist’s thwarted struggles to make his way in the city, mocked and slighted by his sinister Han Chinese boss in a faceless office job, physically rejected when he attempts to enter a building to find accommodation. In his almost mystical fascination with numbers, both as irrefutable markers of meaning within the foggy uncertainty of his experiences and as possible “messages in a code he cannot read,” Tursun’s antihero also resembles the narrators of Samuel Beckett’s major novels, positing a kind of circumlocutory, repetitious, subjective logic to keep his mind from its broader predicaments. One further influence (cited in Darren Byler’s informative introduction to this edition) is Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, another powerful evocation of cultural identity dehumanized to the point of invisibility and anomie through an inherently othering ideology.

If the interior monologue and plotless drift of Tursun’s narrative make for a slow, arduous read at times (in the same way that Beckett’s trilogy can be an arduous read), what brings the novel to life is its vivid evocation of the city as a cloying sensory reality pressing in on the beleaguered protagonist. If his sense of vision and direction is obscured, his other senses seem to be heightened, especially smell and hearing. Unpleasant odors form another layer of bodily discomfort and Sartrean nausea:

The smell of rot was coming to me from every part of the street. Sometimes I sensed the smell of rotten food, sometimes I sensed the various fluids that come from the body, such as vomit, sour sweat and discharge.

The only respite for the narrator is in memories of his family life in the Uyghur village he was brought up in and the rituals of Islamic tradition he adhered to as a boy. They seem glimpses of a more stable past that existed prior to the incursion of oppressive Chinese forces and the brutal fracturing of Uyghur culture to which the novel gives voice. But Tursun is too astute a novelist to permit the oversimplifying lens of nostalgia: the novel culminates in a grotesque memory-sequence involving his alcoholic father and the whereabouts of his mother that suggests the familial breakdown attendant on cultural dissolution.

The final page of The Backstreets gives a timeline that tells of a more challenging compositional journey even than Joyce’s famous appendage to Ulysses (“Trieste – Zurich – Paris 1914–21”):

Written in Urumchi in 1990-91.

Revised in Urumchi in 2005.

Typed in Beijing and finished at 9pm on February 15, 2006.

Revised version finalised in Urumchi at 12.30 am on March 7, 2015.

By any account, then, the novel has taken at least seven years to reach anglophone readers, and over thirty since its earliest iteration. One can only suspect that the situation in Xinjiang has drastically worsened for Uyghur people in the interim, rather than improved. This is a hugely important novel both as an excellent work of narrative art and as the encapsulation of the plight of an imperiled, suppressed ethnic group and its culture. Its translator, Darren Byler, should be loudly applauded for rendering this key text into lucid, well-judged English and bringing it to a global audience, as should his anonymous Uyghur co-translator—tragically, like Perhat Tursun, also now an internee of the prison camps of Xinjiang.

Oliver Dixon

Hertfordshire, UK