One Sky to the Next by Christopher Buckley

Fayetteville, North Carolina. Longleaf Press. 2023. 116 pages.

Fayetteville, North Carolina. Longleaf Press. 2023. 116 pages.

Winner of the Longleaf Press Book Prize, One Sky to the Next ends with the same five words as its title. These identical expressions bracket the entirety of the book and suggest something about the repeating nature of experience, the perseverance of the poet’s quest(ioning), and the poet’s weariness with the limited progress in his quest or change in his understanding of the world. Buckley’s themes and tones are not unfamiliar. With an admixture of nostalgia for better times, of remorse, melancholy, agnosticism, and knowing despair, he is, nevertheless, unyielding (therefore hopeful) in his search for answers to the old questions. Are we alone in the universe? Is there any evidence of God? Why are we here? What are we?

These poems are not without hope, but hope is fettered by strong skepticism. Many poems suggest or even assert our cosmic loneliness, as in “Ars Poetica”: “Every night / the shifting stars / remind me / we’re alone / on the earth, / no matter / what we say.” Other times, as in “Articles of Faith,” the speaker discovers hints of “God” through the language and findings of subatomic physics and cosmology: “I believe neutrinos / know us as angels might, / for our wobbly assemblies / of atoms—they pass / through us as easily as God / particles—confirmed / but yet unseen” and “the light / almost everlasting / in its packets and waves, / in the un-sourced source, / the unknown/ and approximate shores / far from anywhere / we live.” The “un-sourced source” comes as close as this book gets to acknowledging the possibility of God.

What else is the poet to do as he continues to interrogate the universe for answers? Partly, his project is closely similar to that of Rilke in the Duino Elegies, which (in Rilke’s case) is to witness the things of this world and transform them into poetry through an invisible process of the imagination. In Buckley’s poem “Ars Poetica,” we read that “There is an ode for each / cloud, all the heavens to fill / with the unflagging / attention of the heart.” Also, in “Elegies,” he writes: “I have to do what I can / to admire the eucalyptus, / their high white crowns / singing back the sea clouds’ / indecipherable / context of our hope.”

In Buckley’s case, however, the answer is not so settled; he has not, as has Rilke, arrived at his “answer,” at least not fully. In “Beneath a Cemetery Overlooking a Beach,” he writes: “I’m waiting // for more time to come to a conclusion, / waiting for more time to wait.” That said, like a prospector who keeps not finding the gold he seeks (apart from the occasional nugget), Buckley continually searches one day to the next, one poem to the next, one sky to the next. In the concluding stanza of the collection’s final poem, “All the While,” we read: “It’s hard to see / the purpose of the world, / or the need . . . there’s no / breadcrumb trail across / the night, no streaks / of shooting stars leading to / anything . . . We have only the trees / still making way for the wind, the dry / leaves of eucalyptus like swarms / of dead souls let go again—little change, / one year, one sky to the next.”

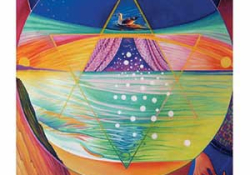

Though it may be hard to see “the purpose of the world,” the poet has not abandoned the search. His is a consciousness keeping company with itself in a state of heightened metacognition, an awareness at full burn, rescuing what it can of experience through acts of remembrance and a current “unflagging attention,” and always holding as much as it can in one (almost) fully globed condition of Being. His best poems strive to manifest this fully globed “holding” with their vertical and horizontal range of topic and image. Buckley has managed to create a unique and persuasive style of writing that serves this project of inclusion and full-range inquiry without sounding strained, bombastic, or ostentatious. On the contrary, there is a completely contemporary and authentic sound to the voice in these poems, deeply human and persuasive. This poet of twenty-seven collections of poetry deserves a much wider reading than he has to date received.

Fred Dings

University of South Carolina