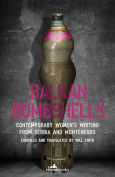

Balkan Bombshells: Contemporary Women’s Writing from Serbia and Montenegro

London. Istros Books. 2023. 143 pages.

London. Istros Books. 2023. 143 pages.

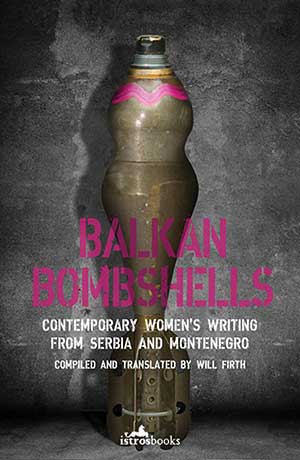

Curvaceous and wearing pink, the old bomb on the cover of Balkan Bombshells has sparked a debate more explosive than the mostly quiet stories it contains. As explained in his introduction, Firth asked Serbian and Montenegrin women authors to submit offerings for a volume from Istros, a UK press that publishes Balkan voices in translation. Though uncompensated, these writers, largely unknown to the West, would thus be heard inside it. But even prepublication, some authors attacked the proposed cover for sexualizing a prime Balkan symbol of patriarchy and violence. Some withdrew; others took their places. Many likewise faulted the West for miming support of its margins while profiting from their labor and wondered how this random collection of writers from only two small nations could represent “the Balkans.”

Predictably, given its genesis, this slim volume is no aesthetic gem. Yet it sharply captures a Serbia and Montenegro still bound by received scripts, patriarchy, and negative fallout from Western postmodern economic and cultural capitalism. In Bojana Babić’s “A Man Worth Waiting For,” a young woman hopes said man will carry her to a brighter place but must marry an older peasant who dwells deep in the forest. In “A Small Death,” by Katarina Mitrović, a woman who fears living draws close to a “real, capable man,” but he prefers Muslim women who “treat men better” and kills the cat she had been playing with. In the story by Olja Knežević, a husband declares himself trapped—by job, commute, and family—yet fails to see how he has imprisoned his wife, who is free only to rebel in tiny ways, like not sending back an undercooked cod in the restaurant where all call her husband Mr. B—the Boss. Marijana Čanak’s surreal “Awakened” shows direct retaliation against male violence: the voodoo doll made by a girl suspicious of men appropriately maims the male teacher who sexually harassed her.

The war as memory appears in many stories, especially two about diaspora. In “I’m Writing to You from Belgrade,” by Svetlana Slapšak, Slobo’s letter to a lover now in Toronto recounts his stay in Belgrade just after Milošević’s death, describing “rivers of people” who need not face “the ruined houses of the neighbors they killed” and still teach women to “become the same—pitiable dolls with frozen brains.” Slobo asks at last, “How can these people listen to Serbian turbo-folk after all that’s happened?” In Milica Rašić’s poignant “Smell,” meanwhile, pregnant Almina’s mother, Alma, dies as soldiers expel them from Bosnia. Abandoning Alma’s body to save herself and her unborn child Ina, Almina grabs Alma’s dress collar; its lavender smell evokes her. Years later, when Ina writes a prizewinning story about the war, Almina will let her visit Bosnia, though warning that she will never know the “smell of war.” Before departing, seeking something to remind her of Almina, Ina finds Alma’s collar in Almina’s wardrobe and begs to take it along. “What is it, Mum? It smells of lavender.” The smell not of war, but of lavender, thus links three generations.

The seventeen stories in Balkan Bombshells, representing multiple genres—e.g., realism, fantasy, ironic humor, meta—imagine a society where isolated, alienated men and women haunted by history face limited choices in their drab postwar reality. Divorced Tomi of “Do You Remember Me?”, by Jelena Lengold, has “forgotten” himself and longs “to touch another human being.” The narrator of Lena Ruth Stefanović’s “Zhenya” notes, “Reality . . . had to be accepted robotically, as the majority did,” while the narrator of “Notes from the Attic,” by Marijana Dolić, states that “the curse of our ancestors’ genes catches up with us. . . . What remains is family.” And in “The Title,” by Svetlana Kalezić-Radonjić, a “liberated” mother rejects the name for her daughter’s “excellent” novel (completed after years of laboring, as wife, student, and mother, in the “bacchanalia of banality”) because “here your life belongs above all to your ancestors and descendants.” But once her mother dies, the author defies tradition: “Gospel of Clitoris” becomes “Gospel of Uterus.”

Finally, then, these generally somber tales, whose frequent irony underscores their bleakness, quietly critique a still poorly understood and often disparaged culture—a small but promising act of resistance that complicates the reading of the cover.

Michele Levy

North Carolina A&T State University