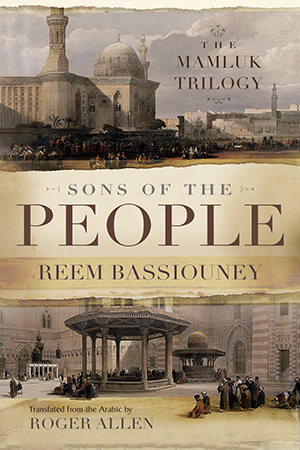

Sons of the People: The Mamluk Trilogy by Reem Bassiouney

Syracuse, New York. Syracuse University Press. 2022. 623 pages.

Syracuse, New York. Syracuse University Press. 2022. 623 pages.

Alexandrian-born novelist Reem Bassiouney has steadily been establishing herself as one of the freshest voices in Arabic literature with a parallel career as an academic in the field of Arabic linguists. In the world of English translation and prior to Sons of the People, readers were introduced to her work through three very readable novels that explore the world of family dynamics and gender politics in late twentieth-century and early twenty-first-century Egypt. The wonderful The Pistachio Seller (2009) became popular with many readers as young upper-middle-class Wafaa negotiated her life in Cairo when she becomes besotted with her cousin Ashraf, who had embraced the values of 1980s Thatcherism. What won readers over was Bassiouney’s ability to maintain readability and accessibility without avoiding discussing complex and difficult issues.

In her equally entertaining Mortal Designs (2016), Bassiouney tackles romance and class in an ironically humorous and dark vein, but this tone has not always found favor with some in Egyptian literary circles, who feel that Egyptian novels need to be far more complex and challenging if they are to be taken seriously. Professor Hanaa (2011), also available in English, was awarded the 2009 Sawaris Foundation Literary Prize along with The Pistachio Seller’s 2010 King Fahd Centre for Middle East and Islamic Studies Translation of Arabic Literature Award, so Bassiouney was not short of accolades, but she was still most definitely seen as a writer of popular literary novels, something that some Egyptian literati don’t see as a compliment.

Against this background Bassiouney was awarded the prestigious Naguib Mahfouz Award by Egypt’s Supreme Council for Culture in 2020 for her historical novel Sons of the People: The Mamluk Trilogy. In Arabic, it had been a bestseller since its publication in 2018 despite being very different from her previous novels—at least on the surface. A trilogy that spans generations from the fourteenth to the sixteenth centuries CE, the novel tackles the turbulent politics of Mamluk Egypt through the prism of individuals and families that are impacted by the historical events. Some Western critics have compared the Mamluk Trilogy to Mahfouz’s Cairo Trilogy, and in terms of characterization this is fair, but in many other ways Bassiouney’s work can be seen to be part of the more recent historical novels exemplified by Egyptian writers like Salwa Bakr and Radwa Ashour, major figures of the late twentieth-century / early twenty-first-century literary scene who had written many accomplished contemporary-based novels before moving into historical works such as Ashour’s Granada Trilogy and Bakr’s The Man from Bashmour. Both of these forays into historical fiction were successful for both novelists and opened up other ways of exploring their philosophical and political interests. Their success, not to mention the phenomenal commercial success of Youssef Ziedan’s Azazeel and Ahdaf Soueif’s Booker-nominated The Map of Love, showed that this was a well-traveled and viable route for an Egyptian novelist to follow. The question, then, is whether Bassiouney is able to do something new with the genre. Picking an era about which contemporary Egypt was already curious, Bassiouney more than sates most readers’ thirst for knowledge about the period. There are occasions in the storytelling when the sharing of historical information interrupts the flow of the narrative, but it is only rarely, and the history of a period dominated by the leadership of foreign-born military elites is so interesting that the jolt is quickly forgotten.

Alongside the historical, Bassiouney explores human relationships just as she did in her contemporary novels, but it is now done by examining the impact of the different styles of leadership on the individual. The most complex of these is the relationship between the Egyptian Zaynab and her Mamluk husband, Amir Mohammad. Forced violently into the marriage, Zaynab’s responses are sometimes difficult to read because, just like with Wafaa in The Pistachio Seller, Bassiouney never takes the easy route out. She acknowledges the realities of relationships—how they are often harsh and don’t make sense, even to those making the decision. Some readers may find the sexual politics of the novel challenging, but Bassiouney revels in those challenges.

Bassiouney also explores the theme of obsession. While in Mortal Designs it was all about building a tomb as a memorial, this time it is the construction of the Sultan Hassan Mosque, which still stands magnificently in Islamic Cairo. Zaynab and Muhammad’s son, Muhammad ibn Biylik al-Muhsini, the historical architect of the mosque, fights to get his vision completed, which is complicated as he is a Son of the People, a son of a Mamluk and an Egyptian woman, who therefore cannot be a Mamluk himself. This passion is wonderfully described in all its personally destructive ways, bringing to life a man we know almost nothing about.

The translation flows well, but this is hardly surprising from the well-regarded Roger Allen, who has many Naguib Mahfouz and Jabra Ibrahim Jabra translations under his belt. The language of the translation has a very US feel to it, and Allen clearly made the decision to give it a contemporary register. Overall, this works really well, giving the novel a real sense of immediacy, though occasionally it does contrast (perhaps unavoidably) with the historical setting.

The biggest concern with The Sons of the People is the book itself. This is a novel that could easily reach a readership beyond those with a specific interest in contemporary Egyptian fiction but at over forty dollars for the ebook, it is very expensive and prices itself out of the book club bracket, despite being a prime candidate for this lucrative market. University presses face huge challenges, but this does seem a big mistake, particularly when Syracuse University Press also published the far cheaper The Pistachio Seller. It can be hoped that this trilogy will find a second life in a new edition that will bring it to the wide readership it deserves.

Richard Woffenden

Leeds, UK