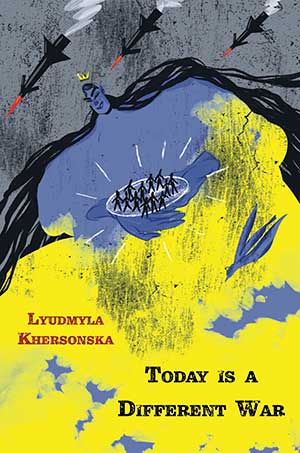

Today Is a Different War by Lyudmyla Khersonska

Medford, Massachusetts. Arrowsmith Press. 2023. 44 pages.

Medford, Massachusetts. Arrowsmith Press. 2023. 44 pages.

Globally, Ukrainian poets are establishing Ukrainian poetry as a decolonization mechanism within a global literature canon traditionally dominated by Russian literature. In turn, these poets establish poetry as means of preservation for documenting the daily challenges and brutality of life during wartime. In Lyudmyla Khersonska’s Today Is a Different War, readers encounter a speaker attuned to and in love with the living world and able to document the war’s destruction because of their connection with their surroundings.

“War. Day 1” captures the shock and awe of waking to an existence radically shattered by a “guest—uninvited and scary.” In it, a door booms, “‘Don’t open’” and “‘Don’t feed it or put on your pretty dress. / If it forces its way in, hit it with an axe—.’” These simple lines echo terrifying headlines and news articles informing the public about Russian soldiers’ intentions in Ukraine: to rape, to maim, to rob, and to kill civilians. The poem is also a testament to Ukrainian fortitude at a time in history when even the best military analysts predicted a swift Russian victory. As “the rockets sang outside the window,” the speaker depicts a woman who “tumbled out of bed in her cherry pajamas.” The woman absorbs the unfolding violence—the “demonic whistle,” the “red blob, flying outside the window.” Chaos unfolds, as does reality: “So the war is here. No one asked it for a visit.” The statements are subtle acceptance and acknowledgment of the situation, but beneath the acceptance, something else exists—a rising determination to survive.

“Where, She Asks, Are My Irises” depicts the horrible elements that have disrupted daily life. Initially, it reads like a simple poem—a woman asks where her beloved irises have gone. She receives an answer:

we denazified your irises,

they were preparing an attack,

planning to join the eu and nato,

stockpiling biological bees.

These lines center the poem. This placement is imperative in not only the context of the poem but also within the justifications Vladimir Putin has used for invading Ukraine. He and his supporters have emphasized that the invasion of Ukraine is to “denazify” the nation. Russia has proliferated—quite effectively—conspiracy theories about US-operated biolabs in Ukraine along Russian borders. However, the speaker counters the accusations, and Khersonska’s poem transforms into a moment of Ukrainian defiance and acknowledgment that what Russia seeks to reclaim, it ultimately destroys.

“The Fourth Month of Constant Shelling” addresses an issue that Ukrainian historian Olesya Khromeychuk describes as “Ukraine fatigue.” In this poem, the speaker states, “It’s okay to kill and wreck, just not in my / supermarket, my train station.” The “Ukraine fatigue” phenomenon has blossomed and contributed to an increase in anti-Ukrainian sentiment. However, the poem boldly tackles isolationism, which, in countries such as the United States, contributes to a rise in alt-right, anti-Ukrainian sentiment. The speaker asserts:

Annul every law and constitution,

erase all those empty words,

to hell with non-existent rights

if we don’t have the right to live.

These lines draw into question the moral obligation of countries like the US and the UK, two of the three signatories to the Budapest Memorandum, which guaranteed security for Ukraine if Ukraine surrendered its nuclear arsenal.

“You Are with Your Country, Wherever You Are” testifies to the war’s impact on native and diasporic Ukrainians. “Wherever you are,” the speaker states, “you hear the whistles and cracks.” Native and diasporic Ukrainians responded to the war with an outpouring of grief, advocacy, cultural education, and humanitarian and military aid. Global Ukrainian communities helped bridge cultural gaps for refugees. The diaspora established vocal platforms, protested the war, and petitioned their governments to support Ukraine. Nonetheless, this poem’s power does not merely accumulate because of its emotional weight shaped by consideration of the diaspora and refugee experiences. The speaker observes that “my country’s children are quiet and look to their parents” and “my country’s children nervously pack their things.” The speaker depicts what Ukrainian children endure:

they sort what they’ve found: shrapnel, bullets, a piece of rusty wire

everything that the “Russian world”—

which they say my country is a part

of—

sends to my country under the cover

of humanitarian aid.

The speaker returns to the “denazification” element first introduced in “Where, She Asks, Are My Irises” and addresses an unfortunate reality for Ukrainian children: some are now more familiar with weapons of war than they should be.

Today Is a Different War is shocking, and these poems are contemporary battle cries and documentaries, observations and declarations. The collection reminds readers and the publishing world why decolonizing literature and uplifting oppressed voices is imperative at this point in history.

Nicole Yurcaba

Southern New Hampshire University