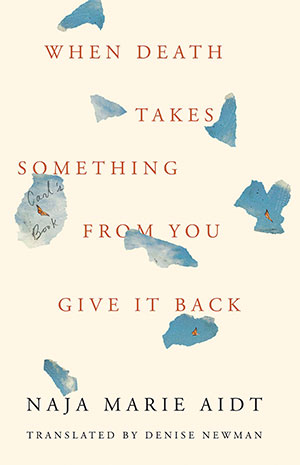

When Death Takes Something from You Give It Back: Carl’s Book by Naja Marie Aidt

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2019. 152 pages.

Minneapolis. Coffee House Press. 2019. 152 pages.

Less than a year after the birth of my son, I sat in a coffee shop with my brother—even more newly minted as a parent himself—and we both, I imagine, rubbed our eyes. My brother, at once baffled and with great clarity, blurted out, “I’m never going to stop worrying that he might die.” To which I, in my instant communion with him on this topic, replied, “And that’s the best-case scenario! That we just worry, for the rest of our lives!” That shared experience of perpetual love and anxiety was like a shimmering web held between us, one built tenuously and out of utter necessity. This was now our constant and indisputable duty, something we had sworn to unequivocally, placing our hands in those early days on the sacred texts of our sons’ warm and burgeoning bodies.

Initially, knowing only one thing about Naja Marie Aidt’s newest work in translation—that it was written after the sudden death of her twenty-five-year-old son, Carl Emil—I imagined myself taking it in slowly. A small pill each evening that my body could become accustomed to over time. In reality, I finished reading the book only hours after I had first, and finally, brought myself to open it. Between preparing dinner and scuttling a four-year-old toward the tub; in a chair, in my room, under the light of the coming on of evening and then, necessarily, by the light of a humming fluorescent lamp; even as I had to stop to tend to my daily obligations, I returned to that small and exceptional book, hungry for the opportunity to bear witness to such honest and unapologetic suffering.

There is more pain in its pages than any lifetime should hold, but somehow it didn’t feel to me as I expected it to: like I might be gathering and holding Aidt’s pain, inescapably attaching it to my own indeterminate fears for the boy in the tub. Rather, I was repeatedly reminded of the words of the poet Kaveh Akbar: “Against everything, we have to protect our permeability to wonder.” Previously, I had taken Akbar’s wonder to mean a thing most easily associated with unbidden joy. But Aidt affirms this “against everything” commitment on a level that I had yet to encounter—in its harshest form, consistently met and renewed, over and over, relentless preservation and questioning of the memory of her son and of wonder itself. And though this process is not often joyful, it looks and feels like something much broader, and though unwelcome—Aidt seems to say—it is here.

Throughout the work, the process manifests in a need to trace and retrace the map of her son’s life and death, a map that does not exist and can only seem to exist after. “I wrote in my journal: / March 30, 1996, evening, bunk beds, Carl Emil, six years old, says: / ‘The sun is a kind of star and the star, a kind of sun. But when you die, you can’t get human skin and human hair again.’” Pages seem to interrupt themselves with foreboding moments like these, as she scans memories, journal entries, and poems for missed signs. But Aidt herself recognizes the imperfect nature of such an approach: “Images and signs cannot be interpreted before they’re played out in concrete events. You only understand them in retrospect. That’s why omens can only be expressed. As language, as poetry.”

Formally, the work feels both fractured and natural; cerebral in the most literal sense, each page moving toward and away from its own patterns with the same rapid and circular cadence as human thought. One of a number of recurring patterns is Aidt’s exploration of the work of writers who have attempted to traverse incalculable loss through language, from Jacques Roubaud to Joan Didion and C. S. Lewis. The accumulation of these works functions as a sort of found artist’s statement. “Most of what I read about raw grief and lamentation is fragmentary. It’s chaotic, not artistic. Often the writer doesn’t have the strength to use capital letters after periods. Often the writer doesn’t have the strength to complete the fragment. It can’t be completed. The writing stays open and pours this inability out through everything that can’t be expressed. A hole in which death vibrates . . .the unfinished and imperfect is the nature of grief. The leaps, unpredictable.”

The fact that there is only one brief moment in which Aidt writes something like hope is balanced by the fact that this moment is the well from which the title of the whole book has been arduously pulled forward: If Death Takes Something from You Give It Back, a moment far too revelatory and perfectly placed within the work to disclose here. It’s enough to say that, in acknowledging all that her son’s presence and life brought to her and to the world, Aidt is able to begin to allow the tenderest petals of new growth, ones that do not in turn take away from the pain we must unrelentingly tend to after a loved one’s death. I hope to never glimpse the immense and terrible garden this must be after the very particular death of a child. Or, to borrow one of Aidt’s miraculous references, what Hans Christian Andersen called “Death’s great greenhouse.”

To read this book is to commune with Aidt and with suffering itself, a testament to Denise Newman’s dedicated and emotive work in translating it from the original Danish. In reading it, I have re-engaged with that fearful web I imagined my brother and I holding and begun to look at it with less fear and more wonder. As it turns out, the duty we both swore to isn’t perpetual anxiety but adequate admiration for the lives of our children—for any single and indisputably worthy life. Which is impossible; the need for which extends alongside each life, well beyond the body.

University of Oklahoma

Braden Denton

Bailey Hoffner volunteers with Poetic Justice, an organization that offers restorative writing workshops for incarcerated women, and hosts a regular poetry night in Norman, Oklahoma. She is currently working to complete her first full collection of poems, If the Honey Is Sunk.