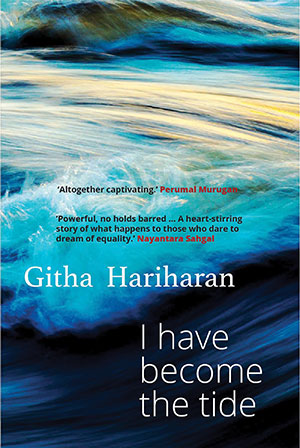

I Have Become the Tide by Githa Hariharan

Noida, U.P. Simon & Schuster India. 2019. 322 pages.

Noida, U.P. Simon & Schuster India. 2019. 322 pages.

In her latest novel, I Have Become the Tide, Indian author Githa Hariharan reminds the world that caste exists, despite many of her compatriots’ arguments to the contrary. Contrasting violence with poetry, she uncovers the subcontinent in a way that helps non–Indians understand it more.

Hariharan’s novel braids together three perspectives. The first considers Dr. Krishna, a poetry professor, who turns Hindu high-caste privilege and history on its ear by theorizing that Kannadeva/Kannapada, a rarely discussed bhakti (or devotional) poet-saint, may have come from the lower castes. Not one of the biographies the professor has read of Kannadeva hints that his grandfather was a cattle skinner or his father was a washerman. Instead, his history “has been whitewashed so Kannadeva can be a ‘saint,’ a ‘Hindu saint.’”

News of the professor’s theory spreads through the country via social and traditional media. Fundamentalist Hindus—whom Hariharan mocks throughout the book by calling them fundoos, as anyone would actually hear on any street in Delhi today—feel scorned by such heresy. One guru goes to unspeakable lengths to wring out his fury, instructing a young disciple to silence Dr. Krishna.

In the story’s second strand, Satya, Asha, and Ravi are Dalits benefiting from the university education reserved for them. They represent the realities of today’s affirmative action. For instance, medical student Satya is tormented by Dr. Sharma, “the anatomy professor who likes to pretend there is a bland space where Satya sits.” Sharma attempts to intimidate the medical student into quitting, blatantly lying about his performance and attendance to get him kicked out. Though they are all bullied in one or more ways, the Dalit university students Asha and Ravi add little value except beyond attempting to show social media’s role in leveling the playing ground between castes. Satya, however, does bring a surprise twist to the plot.

The story’s third strand takes place during an indeterminate time in Indian history. Chittakiah and Mahadevi have escaped villages where people are forced to do labor higher castes find despicable. They raise their son, Kannadeva, in Anandagrama, an intentional community beyond the confines of castes. (Anandagrama, which loosely translates as peaceful plains, is an actual city in India, the supposed birthplace of Krishna.) To give him a better life, the devout Hindu parents send him away for an education and religious training at a temple, where he remains safe when war strikes. One element about this storyline that stuck out was its relevance to today’s global refugee crisis and political division.

I Have Become the Tide shines a light from three thousand feet above the human condition. It is about people giving and taking grave offense through seemingly deliberately misinterpreted intentions and comments. It is about humanity’s perpetuation of a chasm of “us versus them.” Hariharan’s book, she writes in the acknowledgments section, was “born out of the conviction that no writer can engage with life in India today without taking a stand, in some modest way, on the terrible inequalities that continue to ravage the lives of so many of our fellow citizens.”

This book also evokes tears—of frustration and of beauty. This is especially true in the Kannadeva strand. Here the pages sing with the poetry sung, then written, by Chittakiah and Mahadevi: “It’s our work that makes us know the land like it is our child. The work makes us know the river like it is our brother. And the carcass and leather and broom and graves and fields are all our mothers. The mothers who teach us to love ourselves. The mothers who know that this love and this work make us equal to anybody.”

The author isn’t merely paying lip service to Dalits through this book. She brings their literature out from the dark margins. The title, I Have Become the Tide, comes from a line in J. V. Pawar’s poem by the same name, and she’s excerpted that poem in the book’s epigraph: “I’m the sea; I soar, I surge. / I move out to build your tombs. / The winds, storms, sky, earth. / Now all are mine. / In every inch of the rising struggle / I stand erect.”

I Have Become the Tide contains poetic joy and political frustration, all told with storytelling prowess. It encapsulates not only India but the world we live in today.

Nichole L. Reber

Chicago