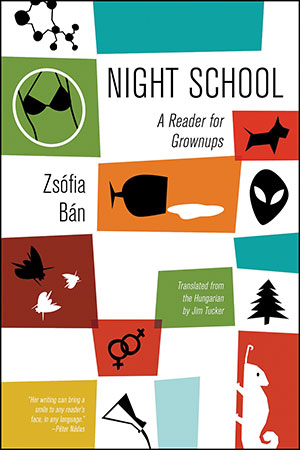

Night School: A Reader for Grownups by Zsófia Bán

Rochester, New York. Open Letter. 2019. 240 pages.

Rochester, New York. Open Letter. 2019. 240 pages.

Hungarian author Zsófia Bán (b. 1957, Rio de Janeiro) fashioned the curious frame of a “night school” to instruct her readers on a long list of random subjects, ranging from Isaac Newton and Mantegna’s Madonna all the way to Frida Kahlo and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Bán thus accepts a tall task. She offers a rather traditional curriculum (with such chapter headings as “Geography / History,” “Mathematics,” “Religion,” or “Physics / Biology”), though she knows that she cannot possibly serve traditional takes on these canonical subjects. After all, night-school students are notorious for getting tired easily, just as readers of avant-garde literature are difficult to shock.

So rather than shocking them, Bán tries to surprise them. The strongest pieces in this “textbook” are tightly narrated stories in which a few select images and elements become the object of playful permutation (as in “A Film 21/1”)—the filmic technique of redoing a “take” here is used for a cumulative, striking effect. Similarly, “What Is This Thing Called the Exchange Reaction? (ˆdestructive affinities)” offers a concisely told travesty of Goethe’s novel Elective Affinities, arranged around the recurring notion of “good chemistry” within the changing couples. Chiseling some of the great monuments of cultural history into pebbles, Bán ends up rearranging the pieces in intriguing forms, to the delight of the already learned student.

Mingled among the many lessons on illustrious subjects are, if you will, electives that present somewhat lighter fare. “On the Eve of No Return” gives voice to famed Soviet kosmo-dog Laika, telling the story of her trip into space (“I’m only whispering because I’m making this recording in secret”) in a story subtitled an “archival recording.”

Each of the short prose pieces collected in this volume is illustrated by small photos, collages, or drawings by Ágnes Eperjesi, and they all end with a few text boxes featuring questions to the reader relating back to the stories: “Discuss in your own words whether this is fair! Argue pro or con!” They accentuate the absurdity of trying to make sense of the factoids and “narratoids” shared by Bán, and they point, in the end, to the rather haughty position from which the author, always prepared to drop yet another cultural reference, tends to lecture her readers.

Thomas Nolden

Wellesley College