Not One Less

An Italian-born Somali writer confronts Italy’s colonial past, beginning with an Italian journalist’s purchase and rape of a twelve-year-old girl, whom he later “gave” to “an old colonist used to having his own harem,” and extending through the Italian feminists who’ve recently become the protagonists of one of the most interesting postcolonial, transfeminist, largely urban responses to Montanelli’s legacy.

For many Italians, myself excluded, Indro Montanelli epitomized a kind of no-frills journalism that no longer exists. He was a man who never concealed his right-leaning politics, nor his sympathies for fascism and Benito Mussolini, whom he affectionately referred to as “Papa.” In the last years of his life, he was the avowed enemy of Italy’s other scourge, Silvio Berlusconi. It was his clash with Berlusconi that caught the attention of the social democrats and liberals. Italians know just about everything there is to know about Montanelli, but for so long, though he certainly made no effort to deny it, no one knew of his colonial past, one that he boasted of often in books and on television programs. Only a handful of us were aware of what he referred to as his “outdoors adventure.” He was twenty-four years old when he was charged with commanding a company of ascari, African soldiers on the Italians’ payroll.

As the Italian-born daughter of Somalis, my country’s colonial endeavor—which wrought destruction in Libya, Somalia, Eritrea, and Ethiopia—is a burden I’ve always shouldered. Not only did I know this history well, but my family had lived through it. One relative fought on the battlefield. Most others either provided support or were employed by the occupiers. In the worst instance, my grandfather served as the interpreter for one of the most loathsome fascist officials, Rodolfo Graziani, who had hundreds of innocent Ethiopian civilians gassed and slaughtered. Doubtlessly I’d been born in Italy thanks in part to colonialism’s influence. When my parents were forced to flee Somalia after Siad Barre’s coup d’état, they chose Italy. They were already fluent in the language and their Somali passports were written in Italian. In fact, Italy’s influence in Somalia lasted for many years, almost until the outbreak of the civil war in the 1990s.

As the Italian-born daughter of Somalis, my country’s colonial endeavor—which wrought destruction in Libya, Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia—is a burden I’ve always shouldered.

There was no way I could ignore this history. I bore its scars on my skin, including that species of Italian racism born of colonialist thinking. It is why I knew of Indro Montanelli, as did countless other children of the African diaspora. The most painful thing about it was knowing that when this man, so idolized in the mainstream Italian media, went on his “adventure” in eastern Africa, he and others like him wasted no time in finding a wife. Many Italians in Africa found women to use as sex objects and cleaning ladies. They were treated like beasts. Naturally, Montanelli followed suit. Yet instead of keeping silent or showing compunction for his actions, he went around trumpeting his misdeeds in the decades following the Second World War.

“She was a beautiful girl, twelve years old,” he said in 1969, on a TV show hosted by Gianni Bisiach. “You must understand that things were different in Africa.”

Many Italians in Africa found women to use as sex objects and cleaning ladies. They were treated like beasts.

Montanelli returned to the topic in 1982 in an interview with the great Enzo Biagi.

“Don’t mistake me for a pedophile. Twelve-year-old girls there are considered women. As a young man I needed a woman, you know. I bought one together with a horse and a gun for five hundred lire. She was a docile little creature. When I left I gave her to General Pirzio Biroli, an old colonist used to having his own harem. I wasn’t like that. I was monogamous because I couldn’t allow myself to be given to that kind of excess.”

He continued writing about it in the new millennium. In Corriere della Sera, he authored a piece about his sexual slave. “It was hard for me to get past the odor of goat fat permeating her hair, and even more difficult establishing a sexual relationship with her because she’d been infibulated since birth. Besides erecting an almost insurmountable barrier to my desires (it required the brutal intervention of her mother to break past), it made her totally incapable of feeling.”

Indro Montanelli used various occasions to describe the sexual violence he’d committed against a minor. It was a crime. But saying “things were different in Africa” underplayed the matter as simply another exotic anecdote among soldiers. That is how the alpha-male Montanelli made it seem, as if it were just a grand game in the end and not a crisis of beleaguered humanity.

At the time, only one woman called him out. She was an Italian feminist of Ethiopian descent named Elvira Bannotti, and she was the one who told Indro Montanelli that what he’d done to that twelve-year-old girl was rape, plain and simple. His statement that “things were different in Africa” lingered over the studio like a dark cloud, as did Bannotti’s increasingly dogged line of questioning. “When we’re talking about what we know about human beings,” Bannotti said, “a relationship with a twelve-year-old girl is a relationship with a twelve-year-old girl. If this were done in Europe, would that be considered the rape of a real girl?”

Montanelli stuttered in response. “Yes, in Europe, yes.”

“Exactly,” Bannotti replied. She continued: “In your mind what difference is there from a biological standpoint? Or psychological?” Montanelli offered a colonizer’s pitiful defense. He considered a girl’s body a war spoil to which he was entitled. This video still circulates online. It has been a talking point for academics, writers (I mention it in my own book Roma negata), and especially female activists.

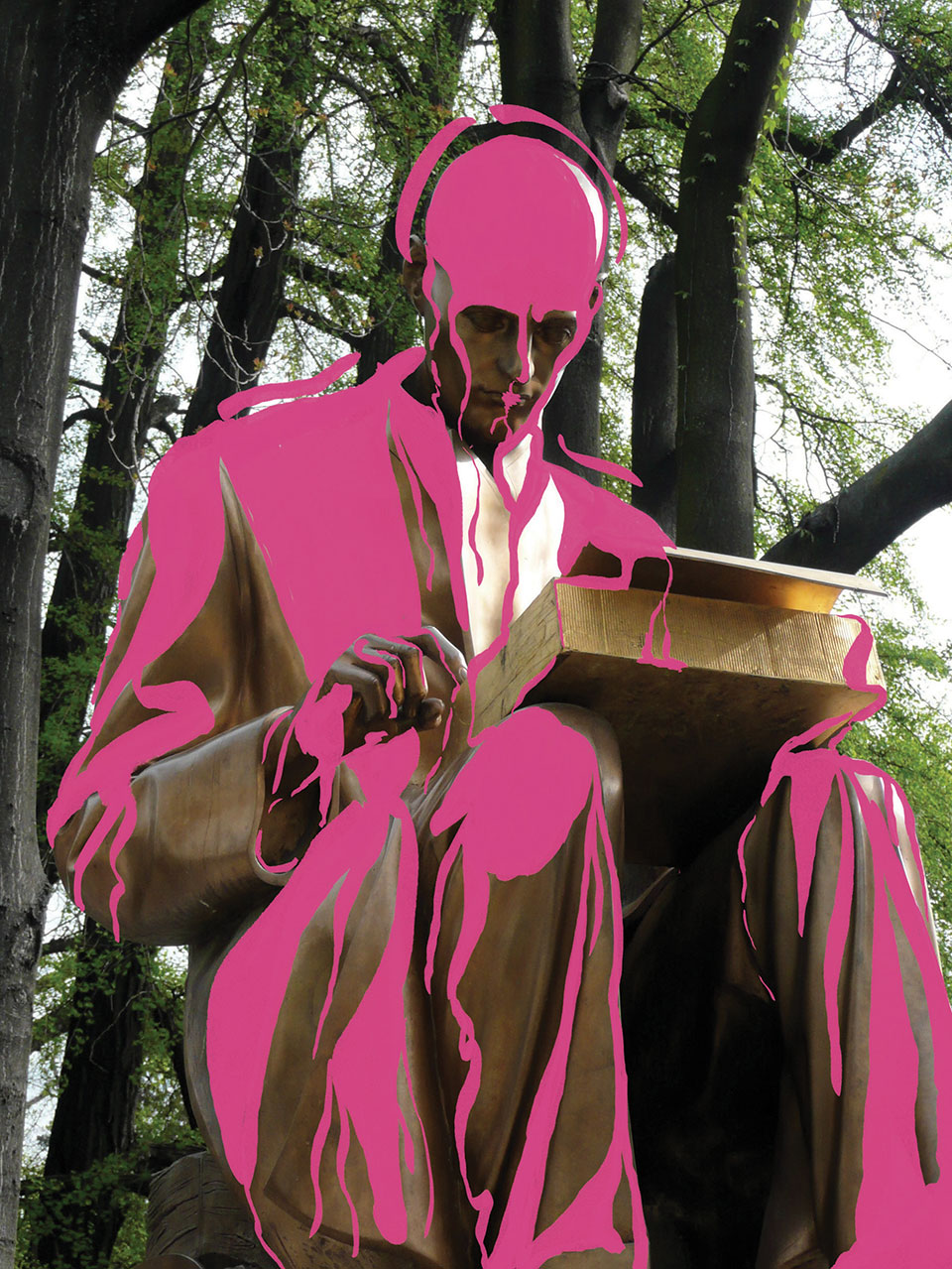

I make special mention of women because it has been Italian feminists who’ve recently become the protagonists of one of the most interesting postcolonial, transfeminist, largely urban responses to Montanelli’s legacy. I learned of it almost in real time from someone who was following the action. “It’s great!” my friend wrote me on WhatsApp. “They poured pink paint on Montanelli’s statue.” I then had to wait for the photos in newspapers to see the monument, doused in pink. It had the appearance of something momentous, something greater than vengeance alone: an expression of desire from one sector of Italian society (it was no accident that this was done by the young women of the transfeminist movement) who wished to renounce the tangle of sexism, racism, cruelty, and unhinged masculinity that Montanelli represented.

Giulia Frova, an activist from that movement, Non una di meno (Not one less), explained to me how the protest began:

They were getting ready for March 8. Usually when there’s a demonstration, there’s a smaller, more hands-on group that choreographs specific movements and things that can be staged along the way. Non una di meno had written a national program. . . a plan to combat masculine violence against women. After we finished that work—and it was something really mature for such a young, grassroots movement with so many different regional hubs—one of the ideas to give it more life, flesh, reality, was to go out into Milan and start chanting the city’s name: città femminista, Milano città transfemminista (Milan, the feminist city, the transfeminist city). We were also trying to get a sense of how our demands could be represented in an urban space.

Giulia told me that while they were brainstorming, the statue of Indro Montanelli came to everyone’s mind, not least because the statue itself was imposed on the city.

“It was embarrassing that the Montanelli statue was in a garden that had always been meant for the public, and it didn’t help that the gardens bordered Porta Venezia, the neighborhood where the city’s Eritrean community lives. In 2004 the gardens were renamed the Indro Montanelli Gardens.”

The pink paint had, in fact, uncovered the venom of Italian sexism and racism.

The movement wasn’t expecting the outpouring of impassioned responses that followed. From one side came the applause of Italian women and antiracists; the other side, mostly media elites, decried the scandal. The pink paint had, in fact, uncovered the venom of Italian sexism and racism. The widespread debates also compelled the intersectional movement to confront the fact of its own predominant whiteness. Conversations touched not only on colonialism and racism but also on how to make black, Chinese, Muslim, and other sisters feel at home in the movement. They asked how they could decolonize Italy and how that change could come directly from their ranks.

For the occasion, I recorded a video for Non una di meno. As I was filming, I felt a welt of emotion. At last, I did not feel alone. There were women at my side who, coming from various social classes, regions, and professions, were finally negotiating the construction of a truly intercultural society in Italy. They had touched on a crucial point. In order to rediscover, on my own, the wounds of my family’s history and the horrid, wicked story of colonialism, I’d been reimagining urban spaces for years.

I was decolonizing cities by telling their stories. Rome, in truth, is still littered with colonial and fascist residues that no one quite knows what to do with: from the fasces of the Mussolini era depicted on manhole covers to the glaring eagles perched atop high columns. There are piazzas, streets, and boulevards with names from Italian East Africa. There’s the African Quarter in Rome and the Cyrenaica neighborhood in Bologna. Wherever one goes on the peninsula, it isn’t all that hard coming across a Viale Somalia, Via Eritrea, Viale Libia.

There are also monuments no one makes a fuss about anymore, which remain as odes to tyranny, bloodshed, and warfare. One has only to think of the statue in Parma of explorer Vittorio Bottego, a man stained by ignoble deeds. It stands tall on the crest of a small hill. At his feet are two figures, Africans rendered as uncivilized, decorative set pieces by the sculptor. And how can we forget the piazza outside of Termini station, in Rome, dedicated to the five hundred soldiers (there were actually fewer) killed in the Battle of Dogali, in Eritrea? There the Italians went to bring the violence of arms and the highhandedness of the colonizer more than the good of civilization.

There would be a multitude of monuments to remember: the Palazzo FAO in Rome (formerly the headquarters for the Ministry of Italian Africa), the Dogali Obelisk, the Duca d’Aosta Bridge. I found another of these forgotten traces in Syracuse. The complex called the Monument to Syracuse Fallen in Africa, dedicated to the Italians who died during the Ethiopian conquest, was initially meant to be in Addis Ababa, but the outbreak of World War II stalled the project. It was instead built in Syracuse in the 1950s, where you can find it today.

I understand the monument as evidence of Italy’s failed attempt at decolonization. It is a fascist symbol, but rather than destroying it years ago, the country took it out (for most of the war it had been in the hold of a ship waiting to set out along the Suez Canal) and reassembled it in Syracuse. The operation ignored the fact that, in the midst of war, Italy (at this point tarnished by laws prohibiting intermarriage) was still peddling the same insidious racialized propaganda that made it an ally of Hitler in a terribly inauspicious war.

One of the figures that catches the eye in the monument is an ascaro, an indigenous soldier who earned a pittance fighting for the Italians. They were the butcher’s meat of colonial carnage. Before sending its own men to die, Italy dispatched these troops. Even now, in Syracuse, the ascaro is bound to the country that enslaved him and which, once the war ended, wasn’t even capable of guaranteeing him a pension. What a pitiful story!

How I wish I could pour pink paint over the injustices unfolding at borders between the world’s numerous Norths and innumerable Souths.

I was always struck by the monument’s location. With everyone’s eyes on Sicily today, it’s no longer a neutral site. It is where migrants disembark, the people from whom Europe has stripped the right to a safe, legal journey. The Europe that emerged after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 built another wall in the heart of the Mediterranean. This wall gave people with strong passports freedom of passage, while those who don’t own any passport were forced to pay smugglers and face unspeakable violence. We often speak of migrants generically, imagining them as statistics. Some mention them as though they were trash. I think they are people deserving of reparations both for the past, when their bodies and lands were exploited and defiled, and the present, when they are denied the ability to move freely.

How I wish I could pour pink paint over the injustices unfolding at borders between the world’s numerous Norths and innumerable Souths. Every now and then I look back at the photograph of Indro Montanelli colored pink. The paint the feminists used is a start. Most likely the preface to a great resurgence.

Translation from the Italian

The Puterbaugh series is a special feature sponsored by the WLT Puterbaugh Endowment. Learn more about the biennial Puterbaugh Literary Festival at puterbaughfestival.org.

Read Aaron Robertson's Translator's Note from this same issue.