Borders

BORDERS, OFTEN CONFUSED for boundaries, are first imagined by groups who insist power over geographies that surpass such insistence. So limits are invented into rivers and forests, divisions fastened to latitudes. The political borders we talk of are intervened into existence but can widen into very real pained places, can be writ into us like “an imaginary line etched / the length of her,” as Celeste Adame writes, or, as Aldo Amparán grieves, become where “another body flecks the desert’s mouth.”* But what is the power of poetry and story against racist shootings, refusals of refuge, caging, and policing—against the separations that rend us? Language, when we find it, is revelatory. It speaks clarity into an ongoing present so we do not yield to a muted history.

These writers cast capacious nets. They hunt songs for us so we might remember what we know. They pull in our horizon with imaginations larger than our cruelties of the time. When we truly reckon border spaces, we know borders not as the edges of who we are and who we are not but as spaces where we verge upon one another, caw to locate each other, eat and work and celebrate; even through terror where we can cry out in recognition, twist with joy.

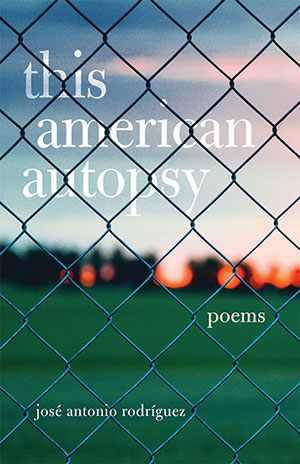

José Antonio Rodríguez

José Antonio Rodríguez

This American Autopsy

University of Oklahoma Press

Rodríguez writes with a reverence for, and a profound sensitivity to, our senses of citizenship, identity, and belonging in this poetic investigation of a country. In poems like “La Migra,” the poet can both beckon and lament: “Let us find a charcoaled corner, you and I, / Where we will lay these words. Leave children / To sleep in windowless rooms. The mother / Biting a prayer. The country weaving a tomb.”

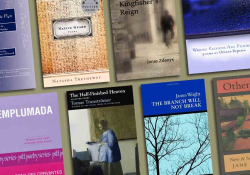

Don Mee Choi

Don Mee Choi

Hardly War

Wave Books

The United States draws its boundaries starkly yet repeatedly violates those of others. Choi braves a poetry that stuns form, that stretches language itself (“incendiary-bomb-shrunken-bodies / so the story of napalm is still being written in Korea”) as she traces the history of the United States’ assaults in Korea, Vietnam, and Cambodia through her photojournalist father’s images of war.

Elidio La Torre Lagares

Elidio La Torre Lagares

Wonderful Wasteland and Other Natural Disasters

University of Kentucky Press

In wrought and buoyant lyric (“my breath turns to ashes / in the soliloquy of the wind”), La Torres Lagares etches the deaths of his own mother and father into a personal and collective account of both suffering and resilience in Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane María. The poet draws to light how the United States scrawls ambiguous borders in its troubling relationship with the world’s oldest colony.

Collected Voices from La Frontera

Collected Voices from La Frontera

Institute of Oral History

University of Texas at El Paso

Directed by history professor Yolanda Leyva, this institute’s vast collection of oral testimonies includes narratives of former bracero workers and offers us a more complex human record of place than any one book ever could. The collection is available online at digitalcommons.utep.edu.

*Quotes are from Adame’s poem “We Follow Water” and Amparán’s poem “Obituaries for the Unnamed.”