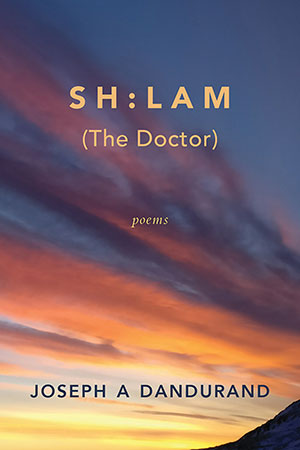

SH:LAM (The Doctor) by Joseph A. Dandurand

Toronto. Mawenzi House. 2019. 84 pages.

Toronto. Mawenzi House. 2019. 84 pages.

Seldom is someone a keeper of deep cultural knowledge and a gifted poet. Joseph A. Dandurand is both. SH:LAM (The Doctor) is “Indigenous Knowledge You Need Now,” narrative poetry imbued with wisdom.

Dandurand, a Kwantlen First Nations poet and playwright from British Columbia, is the 2019 Indigenous Storyteller in Residence at the Vancouver Public Library, having authored several plays as well as three prior volumes of poetry.

SH:LAM’s poems weave a story in the mind’s eye through a series of dramatic monologues similar to British Victorian poet Robert Browning’s but presented from the point of view of one central character throughout. Dandurand’s skill as a playwright and as a poet synergize to create a gripping overarching story describing the postapocalyptic reality of American Indian and First Nations people on this continent yesterday, today, and tomorrow in a way that fits within the larger artistic movement of Indigenous Futurisms.

Anishinaabe filmmaker Lisa Jackson says that from Indigenous viewpoints, “the apocalypse has already happened.” Catastrophic destruction of lifeways and environment accompanied by genocidal attacks and waves of deadly disease started in 1492 at the paracolonial moment. But the term “paracolonial” also asserts continued Indigenous survival as Indigenous peoples, an ongoing process. Elizabeth LaPensée says, “Indigenous Futurisms reflect past, present, and future—the hyperpresent now.” It incorporates elements of but “is not merely ‘Indigenous science fiction,’” and it utilizes Indigenous rather than “Western ideas of space and linear time.” This is very much the worldview of the text.

The central character is an Indian doctor, Sh:Lam—for Kwantlen people, a “medicine man” in the terms of mainstream America. Incorporating the kind of paradox that is part of Indigenous worldviews, he is both (1) the healer who ended the smallpox epidemic for his people historically and (2) a contemporary homeless heroin addict on the streets of Vancouver’s Eastside who lost his children to social services and his love to the needle, both eternal and human. He’s a postapocalyptic Adam eating the apple. While the character is tribally specific and grounded in his culture—as are the allusions and cultural descriptions throughout the text—he also acts as a sort of Indian everyman fighting the onslaught of colonization. In addition to smallpox and heroin, Sh:Lam takes on pedophilic priests from residential schools and those who harm the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (mmiw) for whom so many of us are standing up today.

The richest aspect of this collection, however, is the way in which Dandurand asserts Native perspectives and cosmologies within this Western form to a mainstream audience with ease. In these pages, traditional healing works on the principles it works on in our real lives. The book is populated with nonhuman entities such as Sasquatch and Little People that are very much a part of intertribal Indigenous realities still today, and those beings that non-Natives term “animals”—bears, eagles, hawks, and more—are relatives, sentient actors in our ongoing human story. Shapeshifting is not only possible, it happens.

Dandurand’s collection is a must for readers of Indigenous literature, settler colonial studies, Anthropocene literature, diverse futurisms, or just good poetry. SH:LAM is intense but immensely satisfying.

Kimberly Wieser

University of Oklahoma