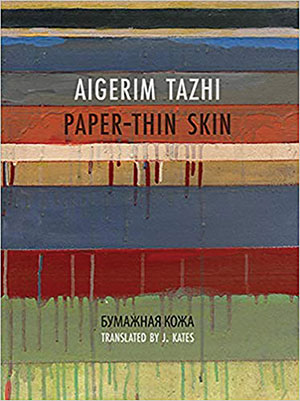

Paper-Thin Skin by Aigerim Tazhi

Brookline, Massachusetts. Zephyr Press. 2019. 147 pages.

Brookline, Massachusetts. Zephyr Press. 2019. 147 pages.

Since she was still a child when the Soviet Union broke up, perhaps it is no wonder that in this volume of poetry Kazakhstani poet Aigerim Tazhi closely observes the edges of things. She writes, “I am sleeping at your doors, under your windows.” The collection’s apt title, Paper-Thin Skin, is taken from the first poem in the collection (“Paper-thin skin translucent, / letters shine through the forehead”). Skin, walls, fences, rims, shores—Tazhi writes of the productive movements and energies such interfaces can inspire: “When the narrator nods off on a mountain of books / They’ll all make their way to the exit. / Three steps at a time. Quickening steps. / A turn to the fence, up and over.”

Here, the contemporary—electronic cigarettes, smog, “news from the bright box,” objects “Made in China”—maps onto an older world of people fishing and knitting, of “reservoirs turned into swamps,” played-out mines, and a “whole city falling apart.” The imagery is inventive: “Leaves are soldered in the caramel depth / and inside all is glass, only a nerve twitches / and cracks a layer of ice” and sometimes delightfully sharp and playful: “trying other people’s heads / on the stake of my neck / in front of the mirror.”

The sonics and wordplay in Russian, though mostly untranslatable, are skillfully brought into an English also sensitive to language by translator J. Kates. Occasional strangeness supports the poem’s effects. In the lines “A runner with a flashlight on his head / grabs frames from the darkness,” Kates’s choice not to use the English word “headlamp” keeps the Russian end-line emphasis on “head,” and the “flash” in “flashlight” reinforces the sense of photographic sight.

Often multilayered and dark—“Earth, dying on the eve of winter / responds to the touch like a cold corpse”—in these poems there is also a sense of possibility: “We will die and wake up as someone else, / . . .surviving our ending without trauma. / . . .we will choose for ourselves.” This is a beautifully translated volume that neither exoticizes nor renders out the joy of reading poetry grounded in another place and language. Against the “obstruct[ing]” sounds of “desiccated tendons . . . on a stringed instrument,” Tazhi’s poetry is a music that explores our shared borders as spaces of opportunity, for the possibility of creating “an imagined world: one that absorbs music from the outside, / and will not preserve the borders / of an internal country.”

Alison Mandaville

California State University, Fresno