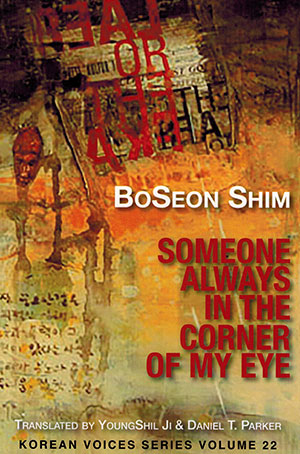

Someone Always in the Corner of My Eye by BoSeon Shim

Buffalo, New York. White Pine Press. 2016. 94 pages.

Buffalo, New York. White Pine Press. 2016. 94 pages.

American readers owe their gratitude to White Pine Press and to translators YoungShil Ji and Daniel T. Parker for making BoSeon Shim’s fascinating Korean poetry available to the anglophone audience. As translated into English, Shim is a master of the contemporary style, writing coyly evasive yet personal poems (see WLT, Jan. 2010, 47–49). Shim’s best poems find their energy in the space between what is hidden and what is revealed. The someone always in the corner of BoSeon Shim’s eye is each person he meets in the world, but it is also his lover. It is also himself.

The collection opens with a suggestion of depth when Shim writes, “There is countless evidence that we have souls.” The evidence, of course, is in the poems, in their depth-reflecting surfaces. Shim can be overtly political at times, but he is at his best when he is elusively personal, gesturing toward the evidence of his own hidden soul. Shim’s poetic strategy of indirectness results in startling and resonant imagery. “I enjoy / questions that are heavy and subtle as coffee at a funeral home,” he tells us in “Questions.” In one of the collection’s best poems, “Foreigners,” he informs us that “This road reminds me of my father’s journal.” Shim insists on his privacy—as he says in another poem, “Breaking up with you is none of the world’s business”—yet he is surprisingly vulnerable in his privacy. The best example of this emotive indirectness is the wonderful poem “Spending the Night Alone in a Motel,” which begins: “I gaze into an evening ocean branded with clouds. / Waves from my unsalvageable wreck swell toward another wreck.” Such imagery reveals more than mere confession ever could.

Shim may remind American readers of John Ashbery’s emotive impressionism. Lines like “A flower falls. / Wandering in time, whirling around / the earlobe of a brief moment,” from the poem “A Flower Falls,” could have been written by Ashbery in his more tender mode. It would be easy to mistake Shim, as it is easy to mistake Ashbery, for a purveyor of cheap surrealism, an easy enough poetic trick. A closer look, however, reveals that Shim’s relationship with the irrational is closer to symbolist than surrealist, or it is surrealist only in the purest sense of the original French movement, in that the oddness of image moves the reader toward a deeper reality, one worth exploring.

Benjamin Myers

Oklahoma Baptist University

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list.