Native in the Twenty-first Century

I’m mixed but that doesn’t mean I’m mixed up—it just means my parents fell in love across a racial and cultural divide that split my blood. When I was young I looked like my dad, my brown hair tipped red in summer—anyone could think I was white, only white, and never Yanktonai Dakota and a little Hunkpapa. But as I get older I look more like Mom, which means I’m mistaken for a variety of ethnicities (people placed bets on their guesses in front of me and never guessed right), which means in small towns or small-minded neighborhoods I experience a taste of Ye Old-School Racism—the kind that shadowed my mother from her first steps, the kind my father couldn’t believe until he saw it in action when they traveled to Rapid City after my aunt’s murder.

I’ve always been Native first and American second, but in youth people forgot that when they looked at me, so I traveled in circles beyond circles—felt like a Dakota spy perched at my listening post to gather information on what the dominant society really felt about us, whatever term it is we’re using now, “minorities,” “people of color,” the tired, inadequate labels that obliterate the rich histories of America’s other-class citizens. I heard what the good people were saying, and the angry ones, the fearful ones, the lazy-minded who think it’s fine to yuck it up at stereotypes and caricatures (“lighten up, already, my God, can’t you take a joke, what’s the harm in a few laughs at some outsider’s expense?”). I would speak up then, I would speak down, around, and sideways, near stand on my head to show there was another way of seeing the world, but damn, it made me tired and dizzy. At least I could shift perspective in a world that said, “Look through the viewfinder and see the Truth,” though that 3D ViewMaster was made of plastic, told sugar-coated stories I knew were myths laid across truth like a carpet to hide all the bones and blood, and the prophets who died in the making of that particular film.

We’re often told, “You’ve come a long way, baby,” and we have, a hundred years followed a hundred years and extermination failed. I’m a citizen of the country my ancestors inhabited before the so-called Founding Fathers moved here and learned from the Six Nations Confederacy the intricate political system that governs us now. If I’d been born a hundred years ago I wouldn’t be a citizen yet because, well, you know, that’s the way it is when you play Manifest Destiny with loaded dice. So why are we grumbling? is the new refrain. Why are we angry after all these years and acres and deaths? And I slap my head with my hand because sometimes I’d like to be lazy, too, look ahead toward the vanishing point and never behind; pretend my feet on this ground are my feet on this ground rather than my ancestor’s brave work. It’s not “magical realism” to see how time resists those easy straight lines. Can’t you see how the past shapes the present and future? How we live what our grandfathers said and our grandmothers sang?

It’s summer again in the twenty-first century as Hollywood gears up for its Blockbuster vision, all Action to keep us distracted with noise. It’s Tonto time and we’re supposed to be grateful because a good-looking actor who may be part Cherokee was inspired by a flying crow in a painting; decided to plunk it on his head, wear the face paint of a Crow man, though his character is Comanche—heck, they’re all “C” tribes, what’s the difference? An Indian is an Indian is an Indian, and we belong to the collective unconscious, we belong to the masses, we belong to everyone but our own selves. Oh, Tonto, I know you had fun imagining what Indian “mysticism” meant to you for a shoot ’em up show, but you’d better take care, our spiritual turf isn’t a playground and sometimes the spirits fight back.

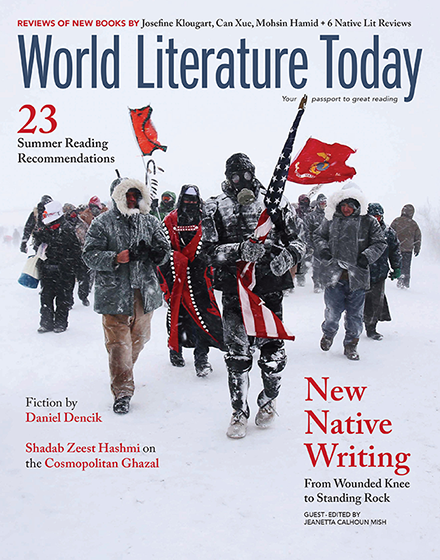

We’re standing up for Turtle Island and the waters, we’re standing up for the future we refuse to gamble away as if it doesn’t matter, as if it should be someone else’s story, someone else’s problem.

The good news is that Natives are on the move, Idle No More, in a country that’s dying from a wasting disease. We’re standing up for Turtle Island and the waters, we’re standing up for the future we refuse to gamble away as if it doesn’t matter, as if it should be someone else’s story, someone else’s problem. We may not be Skins in Space but we invented Science Fiction—the awareness that almighty science divorced from wisdom is a reckless beast. The dominant society made a fiction of our science though their breakthroughs are leading them back to what we knew all along, what we tried to tell them in the very beginning. They’ve been educating us for years, for several lost generations, but we’re up-ending that one-sided desk, that one-sided conversation that can only tell stories in a single direction. Don’t tell us we’re finding our voices in some new academic-artistic renaissance you can study at conferences or exploit in pages on Amazon.com—we’ve been speaking all along as poets and rappers, counselors and prophets, healers and politicians. The problem was, no one was listening to our parents and grandparents, and for certain not our great-grandparents who were too busy facing down guns to hand over their dissertation. You may not want to listen now, but that’s okay, we’ve learned your language and can ride our ponies through communication highways that cross reservation lines. Our ancestors never gave up and they’re singing us awake. We’re inside and outside, listening and speaking, standing up and dancing, connecting and reaching—we’ve got a world to save, yours as well as ours.

Saint Paul, Minnesota