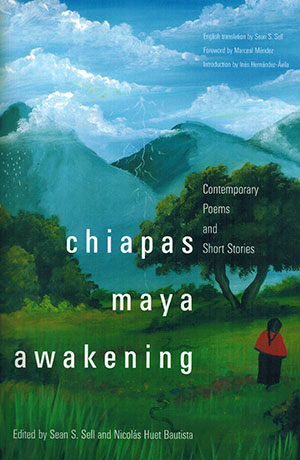

Chiapas Maya Awakening: Contemporary Poems and Short Stories

University of Oklahoma Press. 2017. 185 pages.

University of Oklahoma Press. 2017. 185 pages.

In 1904 Frédéric Mistral was awarded the Nobel Prize for his efforts to revitalize the langue d’oc through his epic poem Mirèio. Now that the langue d’oc has been displaced by French, the work of Mistral withers in the stacks. Until recently, one predicted such doom for the indigenous languages of Mexico as well as their nascent poetry and fiction. Chiapas Maya Awakening, edited by Sean S. Sell and Nicolás Huet Bautista, with translations from Tsotsil and Tseltal, curate the best of poets like Manuel Bolom Pale and fiction writers like Alberto Gómez Pérez. The versions rendered by Sell are sensitive, as is his statement explaining choices he made when working with a language and beliefs alien to anglophone readers. These Maya writers prove that their work is of lasting quality and that their speakers will not forget their mother tongues.

The book opens with an introduction by Inés Hernández-Avila. Since the First Indigenous Congress of Chiapas took place in 1974, the region’s literature has employed narrative techniques of Faulkner, Cortázar, and others, weaving interior monologues, flashbacks, and colloquial language. One of the anthology’s strongest stories is “I Never Knew Anything,” by Alberto Gómez Pérez. Fragmentation and multiple narrators haunt the reader as he, or she, pieces together some peasants’ encounter with Thanatos in the jungle. The story showcases how the contemporary Mayan writer explores tradition while utilizing contemporary narrative techniques.

Images from nature populate the poetry, along with a pensive longing for traditions. Some of the poems by María Concepción Bautista Vázquez are weaker, as their melopoeia can’t be re-created; however, when she uses anaphora, as in the poem “I Am,” the reader can glimpse into the crackling hearth of her imagination, as she finds herself reflected in the “hummingbird” or in the “cricket at night.” The stunning phanopoeia in Bolom Pale’s poetry reveals a great talent. His imagination rivals the deep imagist work of some American poets while remaining rooted in Chiapas: “My vein is a viper under my skin.” In “I Sing in the Tomb” he observes the snail that “traces its shadow with the smoke of silence,” but that memento of oblivion does not darken the vivid voices in this noteworthy book.

Anthony Seidman

Mexicali, Mexico

Get the book on Amazon or add it to your Goodreads reading list.