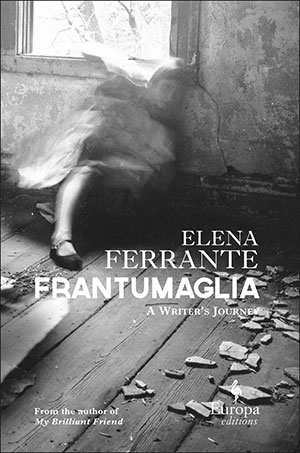

Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey by Elena Ferrante

New York. Europa Editions. 2016. 384 pages.

New York. Europa Editions. 2016. 384 pages.

In 1992 Edizioni e/o published a first novel, L’amore molesto, by an Italian writer who called herself “Elena Ferrante.” Its provocative cover featured a stylish female figure in a red suit—without her head. Eleven years later, the elegant “headless woman” surfaced again on the cover of a collection of Ferrante’s letters called La frantumaglia (2003). Ferrante’s book covers all feature figures with their faces hidden, just as the novelist has hidden her identity for twenty-four years. Explaining her reasons for anonymity to a relentlessly hungry Italian press in 2003, she wrote, “The true reader, I think, searches not for the brittle face of the author in flesh and blood, who makes herself beautiful for the occasion, but for the naked physiognomy that remains in every effective word.”

Reading this collection of Ferrante’s interviews over twenty years (1995–2015), one is struck by her naïveté. Her seven translated novels found a rapt market in the US (1.6 million copies sold of the Neapolitan tetralogy alone), but she has never ceased to be a target for “unmasking.” Whether the secret scribbler is Edizione e/o’s German translator Anita Raja, her husband, Domenico Starnone, or Topo Gigio, her comments on her female narrators and her writing process is revelatory. She describes Neapolitan mothers she has known, for example, as “silent victims, desperately in love with males and male children, ready to defend and serve them even though the men crush and torture them. . . . To be female children of these mothers wasn’t and isn’t easy.” Those children are the ones she writes about, and their friendships are fragile, “without rules.” The “brilliant friends” Lila and Lenù fight and make up—for sixty years—but they are devoted to each other in a way neither is with her men.

Ferrante has much to say here about her birth city, Naples; her childhood; the origin of her plots; and her need as a fiction writer to be “sincere to the point where it’s unbearable.” I was disappointed at inconsistent or odd translations, such as “difference feminism” for il pensiero della differenza, not to mention rendering frantumaglia (her mother’s word for depression) as “a jumble of fragments.” On the whole, however, Ann Goldstein’s translation does justice to the 2003 original, a volume that serves as a “companion” to Ferrante’s fiction.

Lisa Mullenneaux

University of Maryland University College