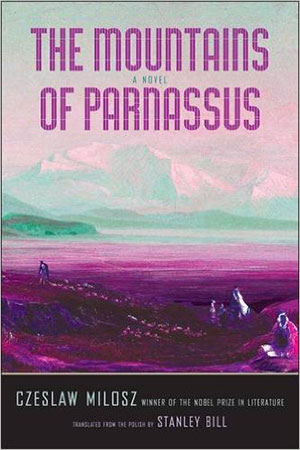

The Mountains of Parnassus by Czesław Miłosz

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2017. 184 pages.

New Haven, Connecticut. Yale University Press. 2017. 184 pages.

Czesław Miłosz, the Polish poet and Nobel laureate who died in 2004, published two novels in his lifetime. The first, The Seizure of Power, was written in 1952 and came out, in French, in 1953. It covers the years from the end of World War II until 1948, when Communism was forcefully installed in Poland. Driven by feverish shifts in plot, as befitting the dicey times it depicted, it remains of interest as a political commentary written for Western audiences keen on learning how the Other Europe came to be. Miłosz’s second novel, on the other hand, The Issa Valley (1955), is a bildungsroman of sorts, featuring the child-protagonist Tomasz. Written in what one might call “highly poeticized language,” it belongs in Miłosz’s oeuvre for its quasi-autobiographical portrayal of the Polish-Lithuanian borderlands. Compared to Miłosz’s main output in poetry and essays, these novels barely register, however, or change drastically our thinking about Miłosz’s aesthetic and intellectual preoccupations.

The recent surfacing of Miłosz’s unfinished science-fiction experiment, which preoccupied the poet between 1968 and 1971, now translated into English as The Mountains of Parnassus, won’t necessarily bring Miłosz new converts, either. Published in Poland in 2013 by a small publisher rather than one of Kraków’s heavyweights dedicated to putting out his collected works, it is a diminutive curio. One might argue that the greatest thing we find between its covers is Stanley Bill’s magisterial introduction. Not only does it illuminate the background of the novel’s inception and eventual abandonment by the poet, it also situates it in the larger context of Miłosz’s life and work. Comparing The Mountains of Parnassus to the magnificent sequence From the Rising of the Sun (1974), Bill rightly points out their mutual “multivoicedness” before zeroing in on the former’s incompleteness regarding the plot, which is, in fact, nonexistent.

Nevertheless, The Mountains of Parnassus tells us something about Miłosz caught in divergent currents of political and social change sweeping across California in the late 1960s. Forces of totalitarianism and religion wrestle for the control of the hearts and minds of four characters—Karel, a young rebel; Lino, an astronaut; Petro, a cardinal; and Ephraim, an exiled prophet—in an unrelenting vision of a dystopian future. While railing against various isms as well as the risks of unmitigated technological progress and the diminished role of the arts in society, Miłosz comes closest to his greatest achievements as a poet and essayist elsewhere. If we read The Mountains of Parnassus as an allegory, then, we begin to appreciate how truly whole and unwavering Miłosz’s beliefs and ideas remained throughout the years; writing a work of science fiction seems frivolous, even silly to us now, but as an attempt to fulfill, formally speaking, the vision of a poet who “always aspired to a more spacious form,” it works, too. That the fragment we get ends with something that more than resembles a poem is salutary in and of itself.

Piotr Florczyk

University of Southern California