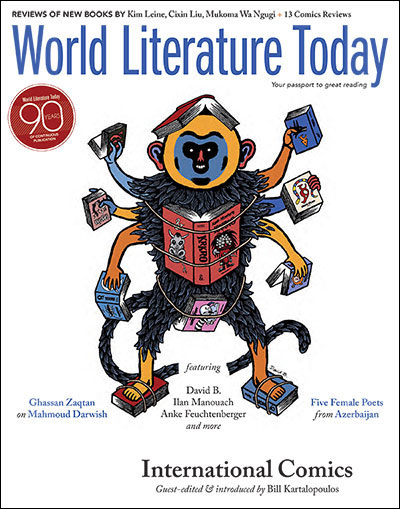

Drawn and Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels

Montreal, Canada. Drawn & Quarterly. 2015. 776 pages.

Montreal, Canada. Drawn & Quarterly. 2015. 776 pages.

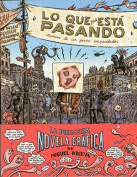

When the first issue of Drawn and Quarterly appeared in April 1990, the cultural landscape for graphic novels and serious comics was almost bare. Yes, Pantheon had published Art Speigelman’s first six chapters of Maus to acclaim in 1986, but superheroes dominated the genre at the time and Maus was considered an anomaly. But Chris Oliveros, the founding father of D&Q, was indeed visionary. The quarterly itself ceased publication in 1992, but Oliveros and his talented staff moved onto even grander endeavors. In the twenty-five years since 1990, D&Q, based in Montreal, has become a driving force in the publishing of graphic novels. This new and hefty 776-page volume attests to that fact.

Not only does this anthology serve as a compendium of comics, essays, and excerpts from graphic novels, it is also a quirky and complete history of the evolution of Drawn & Quarterly and of the comics genre. In a complex introductory layout, the history of D&Q by Sean Rogers is bordered by the chronology of D&Q running along the bottom of the pages. Interspersed are a variety of statements from artists, observers, and D&Q staff, often in bright orange boxes. The collection then finds its pace with essays about artists and a compendium of comics. In an odd and rather engaging way, the awkward layout of the opening pages sets the reader up for the idiosyncratic artistry of the drawings that follow.

D&Q contributors such as Chris Ware, Lynda Barry, Daniel Clowes, Adrian Tomine, Kate Beaton, Chester Brown, Seth, and Joe Matt are writer/artist stars in the graphic novel universe. But one of the delights here is in discovering others, perhaps not so well known or maybe just less publicized. Julie Doucet, James Sturm, and Miriam Katin are not necessarily familiar names to many, but may, I believe, become new favorites (see WLT, Nov. 2007, 14–18). Additionally, the short essays gathered here are quite incisive and often surprising—who knew that Margaret Atwood loved the work of Kate Beaton or that Hillary Chute, an academic who studies comics, is a great fan and drinking buddy of Lynda Barry, or that Adrian Tomine could be so eloquent in his appraisal of Yoshihiro Tatsumi? And it is an added pleasure to reencounter Tove Jansson’s Moomin strips in these pages.

As James Sturm says in a small essay about Art Spiegelman’s Maus, “I began to understand cartooning as choreographed doodles that have to dance with all the other formal elements of the page (word balloons, text, panel borders, etc.) with the intention of being read as a singular performance.” This collection will not, and should not, be read as a singular performance, but as a compendium and resource for anyone interested in or inspired by comics, cartoons, or graphic novels. It is an education in itself and an outstanding primer for artists or students of the form.

Rita D. Jacobs

Montclair State University