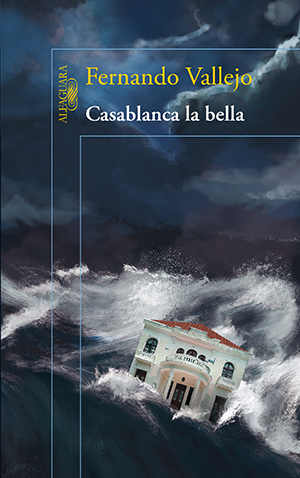

Casablanca la bella by Fernando Vallejo

Madrid / Bogotá. Alfaguara. 2013. ISBN 9788420415574 / 9789587586008

Colombian author Fernando Vallejo (b. 1942, Medellín) is currently in a privileged position within the world of literature written in Spanish. If we were to rank the best Spanish-language writers from the last twenty years, Vallejo would occupy a favored seat next to Ricardo Piglia, Roberto Bolaño, and Enrique Vila-Matas. Few contemporary Latin American and Spanish authors have been able to show their irreverence and political incorrectness, as well as their sense of humor and wit, as Vallejo does. In the novel Casablanca la bella, Vallejo is more wicked than ever before; he writes in the same way as a sniper shoots—knowing he has nothing to lose. What is his target? As always, God, death, and Colombia.

Colombian author Fernando Vallejo (b. 1942, Medellín) is currently in a privileged position within the world of literature written in Spanish. If we were to rank the best Spanish-language writers from the last twenty years, Vallejo would occupy a favored seat next to Ricardo Piglia, Roberto Bolaño, and Enrique Vila-Matas. Few contemporary Latin American and Spanish authors have been able to show their irreverence and political incorrectness, as well as their sense of humor and wit, as Vallejo does. In the novel Casablanca la bella, Vallejo is more wicked than ever before; he writes in the same way as a sniper shoots—knowing he has nothing to lose. What is his target? As always, God, death, and Colombia.

The premise of Casablanca la bella is simple: the protagonist—who is the same in all of Vallejo’s novels—buys (without seeing it first) a house in Medellín, Colombia, the city where he was born. The house is located in an old neighborhood in which traditional homes have been replaced by new construction. Because the house needs repairs, the protagonist hires electricians, plumbers, and painters who turn out to be useless and who damage and ultimately destroy the house.

After arriving in Medellín, he realizes his inability to deal with this city in which he has not lived since his childhood. In this new Medellín, it is impossible to find a fountain for the garden, toilets are not what they used to be, and the people who should help him rob him. In sum, the house’s repairs seem to exacerbate the disaster that already exists. Time has passed, but the narrator is the same, and he is not ready to accept the new country. His nostalgia is quite bitter and hysterical; Colombia is a problem, in the same way everything that one truly loves is a problem. In this way, the house, at times, transforms into a metaphor of Colombia, a country that has changed and that is now impossible to recognize. All these complications can only translate, as usual, into the one problem that appears in different forms, again and again, in this author’s entire oeuvre: Vallejo (or whoever narrates this story) against the world.

Vallejo’s diatribes inevitably arrive at referencing the creator of the universe: God, who has the ultimate responsibility. Casablanca la bella is almost a religious work but, of course, characterized by a negative religiousness that reveals a profound and furious nostalgia for the one who appears to be the cause of all the author’s misfortunes: God, the Father and Creator, and his son, Cristoloco (Crazy Christ); God, who created man, woman, and, of course, Colombia. Casablanca la bella shifts from being a story that narrates the problems of an old house to being a tale that describes the ills of the world, according to the narrator. However, this discourse, loaded with diatribes (so typical in Vallejo’s world), always ends up demonstrating that his writings are impregnated with an unusual and stunning spiritual freedom, a kind of freedom that also makes us laugh and dance, a kind of freedom that not many authors could exhibit with pride.

Marcelo Rioseco

University of Oklahoma