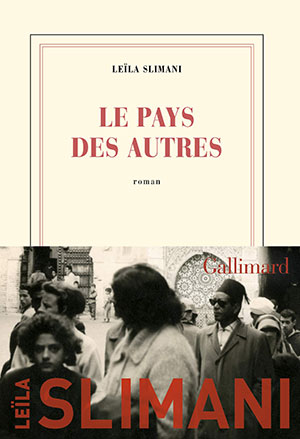

Le pays des autres: La guerre, la guerre, la guerre by Leïla Slimani

Paris. Gallimard. 2020. 365 pages.

Paris. Gallimard. 2020. 365 pages.

IN 2016 LEÏLA SLIMANI won the Prix Goncourt, France’s most prestigious annual literary prize, for her novel Chanson douce (see WLT, May 2017, 104). Slimani’s new novel is mostly set in her native Morocco and spans the period between the end of the Second World War and the country’s independence in 1956. The two main characters are Amine, a Moroccan soldier from Meknes who is serving in the French army during the war, and Mathilde, a young Frenchwoman who endured the rigors of living in occupied Alsace during her adolescence. The two fall in love, marry, and settle near Meknes, where Amine owns a plot of land that he plans to develop into a prosperous farm using modern methods. Mathilde is thus transplanted to a country that has been a French protectorate since 1912, and where the struggle to obtain independence will quickly intensify and lead to a wave of violence.

For the young couple, difficulties arise almost immediately. Amine’s relatively isolated farm is rocky and arid, requiring ceaseless, grueling work. Mathilde is rejected by the French colonizers for having married a Moroccan, and by many Moroccans because she is French. Nevertheless, Amine and Mathilde start a life together and have two children, the eldest of whom turns out to be a very promising student when she starts attending a French school. Much of the narrative is devoted to Mathilde’s attempts to fit in with her husband’s family, while maintaining some level of autonomy.

Announced as the first part of a trilogy, partly based on Slimani’s own family history, the “country of others” is thus the beginning of a multigenerational saga that will follow various characters from the first novel, within the evolving sociocultural context of Moroccan society, up to the present day. For the author, while there are few innovations in terms of literary technique, Le pays des autres is a much more expansive novelistic project than the short, focused novel that made her famous. Slimani excels at detailing the contrasting emotions of each major character. On the other hand, in some instances she simply describes the characters’ actions and leaves their motivations for the reader to decide. Similarly, while most of the narrative is recounted in chronological order, there are a few temporal gaps, followed by unexplained plot twists, which would no doubt be well suited to a film adaptation.

Overall, this novel does what the first part of a trilogy should: make readers look forward to the following volumes.

Edward Ousselin

Western Washington University