Look to the Law: On Translating the Poems of Ennio Moltedo

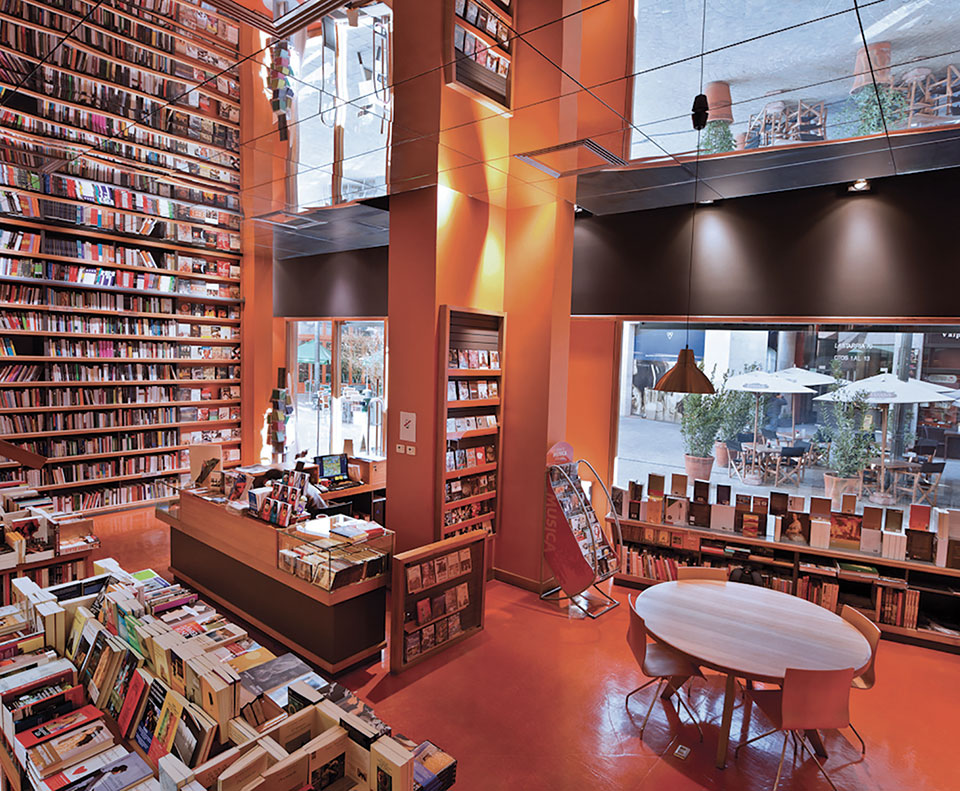

I ARRIVED IN Santiago de Chile on a blisteringly hot Sunday afternoon in early December 2016, too travel-weary to go exploring. But of course I set out anyway, with no sense that my working life was about to take a surprising detour. Wandering through Lastarria—an artsy and bustling old urban village—I turned into a lovely little square and found a terrific bookstore: Librería Ulíses. Before long, my arms were full of recently published books I intended to buy. And then, over my shoulder, came a booming voice: Basta con la narrative argentina!! Este es el país de poetas!” (Enough with the Argentine novels. This is the land of poets!) The voice came from a surprisingly delicate-looking man—Jorge Rosemary, bookseller, poet, publisher—who sat me down and for the next two hours brought me book upon book of Chilean poetry. My reaction to Ennio Moltedo was immediate and physical: as I read, the lines felt like they were passing right through me. That I am now translating Moltedo’s body of work is an ongoing gift from Jorge.

Revered in Chile among readers and critics of twentieth-century Spanish-language poetry, Moltedo (1931–2012) has been compared with Cavafy for his allegiance to a city at once mythic and mundane; with Char for the inventiveness of his political poems; with Saba for his mastery of extreme concision. The poems that appear in this issue of WLT are from La Noche, a collection of 113 prose poems written in response to the Pinochet regime but that also seem to arise from the present political moment—here and abroad—of brutal corruption and cruel politics.

A native of Valparaíso, Moltedo is a poet of the sea, and his connection to ancient Mediterranean poets is manifest in his poems. The son of Italian immigrants, he was strongly attached to the Italian community of Valparaíso and adjacent Viña del Mar. He staunchly refused to relocate to Santiago, Chile’s political capital and seat of the cultural establishment. Moltedo, who daily strolled the streets of his port cities, was part of a tight-knit circle of local writers and artists. For many years, he was director of the University of Valparaíso Press.

After his first book was published, Moltedo decided he would never again write according to externally driven meter; he delineated everything he’d written thus far and never again wrote poems in verse. He sought a deeper, more subtle music, whose sonorities would release the shape of sentences, the energy of images, and fuel a prosody of rhetorical power.

Moltedo’s lines are always plain in terms of diction and vocabulary—a trait that only heightens their surrealism, lyricism, and political force. His rage is exquisitely controlled in tight syntax and in images that appear surreal but are grounded in material fact. One example is the “blue envelope” in “12,” which suggests the paperwork associated with employee firings.

Because my Spanish is so Argentinean, Moltedo’s rhythms have been challenging. But what a pleasure to retrain my ear, to learn to hear anew a language in which I’ve lived for much of my life. Moltedo likes to employ specifically Chilean legalistic, military, and bureaucratic turns of phrase (the better to skewer Pinochet’s institutions); my guides for this vocabulary have been the Latin Americanist Jonathan Pitcher and especially Montserrat Madariaga, a journalist and scholar from Valparaíso who conducted an extensive series of interviews with the poet over the months of his final illness. This first publication of Moltedo in English is the fruit of literary generosity and friendship—a fitting tribute to a poet whose own gift for friendship was legendary.

Editorial note: Read five of Feitlowitz’s translations from this same issue.