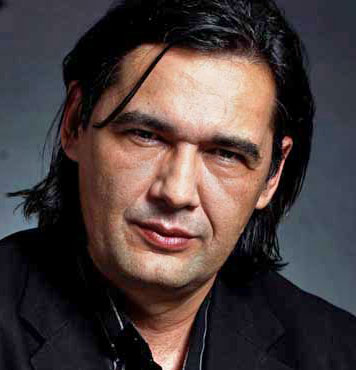

Rebel with a Cause in Serbia: A Conversation with Zvonko Karanović

Like the poets of the Beat generation from whom he takes inspiration, poet and fiction writer Zvonko Karanović (b. 1959, Niš, Serbia) has traveled widely throughout Europe, hitchhiking and often changing jobs. He has worked as a journalist, editor, radio host, DJ, and concert organizer and owned a music store for thirteen years. For many years, he has been an underground cult figure and seminal influence on a generation of younger poets. His early writing bears the influence of Beat literature, film, and pop culture, from which he developed a style described by some as “dark neo-existentialism.” The PEN Translation Fund’s advisory board called Karanović “a countercultural icon [who] writes in a vivid, sophisticated vernacular of desire and transcendence amid cultural and political change.”

Karanović has published seven collections of poems. His novel trilogy, The Diary of Deserters, is the first such project in twenty-first-century Serbian literature and is comprised of the novels More Than Zero (2004), Four Walls and the City (2006), and Three Snapshots of Victory (2009). His work has been anthologized, most significantly, in New European Poets (2008). His poems have been translated into several European languages. He now lives in Belgrade.

Biljana D. Obradović: People have said that you are “a poet of urban melancholy.” How would you define your poetics?

Zvonko Karanović: I am an impressionist—I deal with emotions.

BDO: I noticed that you are one of the few Serbian poets not to have studied philology or philosophy. Yet you decided to pursue literature. How come?

ZK: I was interested in painting, but my parents didn’t have enough money to send me to Belgrade to study. So, to delay my army service, I enrolled at the technical faculty in Niš. I didn’t know what I wanted to do in life. I spent my days away from home, hanging out with friends, watching movies, reading books, going to rock concerts. That is when I “discovered” poetry at the age of twenty-one.

BDO: Your early poems are quite urban, and in them one can clearly see that you were influenced by American music and poetry.

ZK: In the beginning I was writing short poems, not longer than three or four lines. I wanted to capture “the feeling,” “the situation.” I’ve been partial to the marginal, the underground, off-center things. I despised official institutions of culture and never tried to publish my work. I considered informal publications the place for my poems. In those formative days, I mostly read American poetry. Luckily, there were translations of Whitman and Pound, classic anthologies of American poetry, but also of Beat poetry and underground poetry, New York School and Black Mountain poets, and underground poets. I consumed everything I could find.

BDO: In your first collection of poetry, Blitzkrieg (1990), there are poems of love, rebellion, music, and popular culture. Many of these have been illustrated with your artwork. How did this collection come about?

ZK: After coming back from the army in 1986, I started writing longer, narrative poems, and I decided to start sending my work out to literary magazines. I sent out the old, shorter ones and the new, longer ones. I began publishing my poems everywhere, and within a few years I gained quite a good reputation. The time had come for a first collection. While I was putting it together, I realized I had two books: one of poems from the first half of the 1980s and one of newer poems. That’s how two books came to be: Blitzkrieg and Silver Surfer. I decided to go with the new poems. While I waited for the book to come out in print, I wondered what to do with Blitzkrieg. It contained the nucleus of my poetics, and I didn’t want to give it up. I decided to print Blitzkrieg myself, at home, in a photocopy version. I passed this edition out to friends and acquaintances. Blitzkrieg was only officially published nineteen years later, as part of the selected poems (Box Set, 2009). Half of the forty poems were illustrated by a very talented, young Belgrade artist. The illustrations included the main character, who was supposed to represent my alter ego from the eighties, a young man in tight jeans and All Star sneakers who dresses and has a haircut like the guys from the Ramones.

BDO: Your first official poetry collection, Silver Surfer (1991, 2001, 2009), with its thirty-nine poems, is a great achievement, with a clear American cultural influence.

ZK: Even though it was socialist, Yugoslavia at the beginning of the eighties was a great place to live: we had money, we could travel without the need for a visa everywhere, record shops were filled with the newest licensed musical editions, and bookstores were filled with translated literature. Because of rock music, film, and literature, my whole generation and I were turned toward the West, especially to the US. We were fascinated by American culture, primarily by the beatniks, the San Francisco music and comic books scene, pop art, the work of American underground authors from Bukowski to Hunter S. Thompson.

BDO: Rock music plays an important role in your work, as do the Beat poets and writers. The epigraph of your collection Silver Surfer is a quote from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and your favorite movie, Easy Rider, takes place in New Orleans. How did that come about?

ZK: I discovered poetry later in life. I came to love the Beats and American poetry accidentally through texts by and interviews with Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. Then a whole new world opened up for me. The Beats’ antiwar sentiments, the destruction of all taboos, the openness to new experiences, the equality between life and writing, the spontaneity, the giving of all yourself had a huge impact on me.

BDO: Here you experiment quite a bit with the form of the free-verse poems, play with white space, and avoid punctuation (but not capital letters); many of these experimental elements remain in your poetry to this day.

ZK: Kerouac said, “Say the truth of the world in an interior monologue . . . What you feel will find its own form. . . . Be susceptible to everything, be open, listen.” His encouraging words made me describe the world as I saw it. I didn’t worry about the rules. Ginsberg used to say that everything that passes through the human mind is appropriate for poetry. . . . He destroyed the walls for me between “high” and “low” literature. That is how I began to write. I didn’t think about form, I picked it intuitively—whatever I thought I could use in a poem, I did.

BDO: Also, some of your Surfer poems are written from the perspective of a female voice.

ZK: All my poems are in essence some kind of stories, fragments of situations. . . . In Surfer, two such poems are imaginary confessionals by Patti Smith (“Pissing in the River”) and Nico, the singer from Velvet Underground (“All Yesterday’s Parties”). That change in perspective was very interesting to me as a writer, so I have used it in later books.

BDO: Many people see Silver Surfer as a cult book, especially younger readers. Looked down upon as too American by the mainstream, still it inspired the alternative underground culture and a fan club begun by young people who saw you as someone to emulate. Finally, with the collected verse titled Box Set, in which the Surfer poems are included, you may have entered the Serbian mainstream.

ZK: Silver Surfer is in a way a book of rebellion, primarily in relation to the national literary canon. It uses a new language and form; it’s more urban; the themes speak about alienation, loser-dom, loss of friendship, lost loves; drugs are openly mentioned; rock iconography is very present—therefore, it contained everything that did not exist on the domestic literary scene at that moment. It was clearly “an American book” against the Balkan tedium, read mostly by young people with a cosmopolitan orientation who (I suppose) wanted to identify with someone who thinks like them, feels like them, and who speaks about the things that are happening to them. Surfer quickly became an underground hit. The edition soon sold out. Unfortunately, publication of the book coincided with the beginning of the Balkan civil wars. There were no new editions. People photocopied that collection. There were cases of unfamiliar people writing to me, even from parts of the country gripped by war, to mail them the book.

BDO: In many poems of this collection, the narrator wishes he could emigrate from his country. The socialist architecture and life seem claustrophobic.

ZK: In the Surfer poems, I captured a desire for escape that comes through several poems (later it will become a dominant theme) and is a direct consequence of the political events which preceded the military conflicts and the disintegration of the country. The end of the eighties brought an accumulation of dark clouds of nationalism, which culminated with the civil wars (1991–95). The poems that were included in Silver Surfer were created in the prewar period (1987–90), so that some of them, between the lines, capture the atmosphere of the rising claustrophobia and premonition of the forthcoming dark times.

Perhaps I owe this to Bertolt Brecht and his antifascist poems, which I read in my youth, or perhaps to the positions about truth as a leading ideal in art, which reminded me of who I was, as a poet, with a responsibility to follow the truth. The terror can only be overcome by witnessing it.

BDO: Then it’s clear why in your next book, Mama Melancholy (1996), we can see many apocalyptic images and a wish for an escape from reality.

ZK: After 1990, Serbia was measured by media spin, voices of hatred, hyperinflation, and the black market. Many emigrated from the country. The ones who stayed behind, including me, were sentenced to dealing with the new circumstances every day, which included standing in lines, getting gas from plastic bottles [the sanctions on Yugoslavia limited gas imports], hiding from the MPs. Dark images were all around me. I began to think of society, war, death, and this ultimately affected my poetry. My poems became darker and more melancholic, politically engaged. Perhaps I owe this to Bertolt Brecht and his antifascist poems, which I read in my youth, or perhaps to the positions about truth as a leading ideal in art, which reminded me of who I was, as a poet, with a responsibility to follow the truth. The terror can only be overcome by witnessing it.

BDO: So you turned to the poetry of witness?

ZK: Of course, but there were other themes. I was overcome by a crisis: having turned thirty, I felt claustrophobic; life was passing me by. I fought it by endlessly watching movies, listening to music, and self-destructive conduct. Unconsciously, I developed a technique of forgetting. The poems I was writing then were the only testimony of my life.

BDO: In the next book, Extravaganza (1997), you continue with the chaos in relation to the war and political unrest, but there are glimpses of your personal life.

ZK: Extravaganza was conceptualized as “one year in my life,” representing four annual seasons, starting in 1996–97, marked with street protests and demonstrations against the [Milošević] regime, in which I, too, was a participant. Besides the politically engaged poems that I continued to write, there is a presence of the theme of love as a fragment of life’s ever-present ruckus and everyday uncertainty.

After the end of the NATO intervention, in spring 2000, I realized that I was totally broke, without any energy, stuck at the bottom. I felt incredibly tired from everything that I had experienced during the past decade. That’s when I reached for Ginsberg’s selected poems, which I hadn’t been reading for years, and found the poem “America.”

BDO: In Dark Highway (2001), the speaker cannot handle anymore what’s happening, seems scared, tired, exhausted . . .

ZK: The end of the nineties was marked by the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia. Since the country was officially at war, total mobilization was declared, so that I, like thousands of others, was drafted (I’d be jailed if I evaded it). I was in uniform for seventy-two days, but luckily in the rearguard, far away from the front and without firing a single bullet. The last days of the war, through the method of automatic writing and mind flow, I wrote the long poem “Dark Highway” in order to find answers to all the absurdities that had been going on in the nineties.

After the end of the NATO intervention, in spring 2000, I realized that I was totally broke, without any energy, stuck at the bottom. I felt incredibly tired from everything that I had experienced during the past decade. That’s when I reached for Ginsberg’s selected poems, which I hadn’t been reading for years, and found the poem “America.” That seemed to wake me up. And then in two days I wrote a response, another long poem I was going to title “Serbia,” but which I ended up calling “Great Fatigue.” The poem is cynical and an accusatory confession. Because of these openly antiregime stances, I couldn’t publish the poem anywhere. After the regime fell, I got an opportunity in 2001 to officially publish those two poems. That’s how the collection Dark Highway came to be.

BDO: Taking Off (2004) was published in Serbia’s democratic period.

ZK: After the arrival of democracy in 2000, I didn’t write for almost two years. I was exhausted and tired of the decade of nightmares, and at the same time disgusted by looking at the “winners” who sought a place and grabbed privilege in the new system. Still, wishing to “close” my poetics, I decided to go over “my” themes, now looking from a distance, in a slightly cynical and bitter tone. I spoke for the first time about writing. The title of the book is another explicit stance about my poetry as some type of undressing, an emotional bearing of it all. Poetry has taught me that humans become the strongest precisely when they are the most hurt.

BDO: After this collection of poems, you didn’t write poetry for a while, and instead turned to prose and your trilogy of novels, Diary of a Deserter (2004–2009).

ZK: As I had closed my poetic cycle with Taking Off, the writing of novels was a special “expansion of the area of struggle.” Through my prose, I wanted to explain to myself why that terrible civilization’s defeat of the pro-Western, European-oriented society (to which I, also, belonged) occurred in the nineties in Serbia because of the nationalists. That defeat was the central period of my life.

The three novels are about three best friends from the city margins, not saints or sinners, resourceful and prone to vice, sometimes strong, sometimes weak, but tough and hungry for life. In Serbia at the end of the nineties, they exist on the black market, trying to survive the tough times. They don’t give up living “under their own rules,” ignoring reality. All three are “deserters” of everyday life and the society that surrounds them. The story about free people in an unfree country is the motto of the trilogy. This trilogy desribes the generation of Serbian youth who lost a great deal—some left the country altogether, some felt marginalized because of their pro-Western views, and others got wounded or ended up dying in the civil wars.

BDO: Your new verse collection, Sleepwalkers on a Picnic (2012), consists of prose poems. What inspired it?

ZK: I found my inspiration in surrealism, to which I returned through classic and new achievements, but also through films by Buñuel and Lynch. I wanted to experiment with form as well. That is how Sleepwalkers on a Picnic was created, a collection of poems in prose, where each poem can be treated as a story.

BDO: We have seen your work in some anthologies and some literary journals in the US. Will we be able to see a selection of your work in the US soon?

ZK: Yes. My translator, Ana Božićević, and I have assembled a collection of poems we hope will soon introduce my work to an American audience. America is my spiritual homeland; therefore publishing this collection in the US would be very emotionally meaningful to me.

BDO: Are you worried about the future of poetry?

ZK: No, poetry has existed for millennia, as it is an essential need of humans, even though they may not be aware of it. The deepest human need is to prolong life through writing.

September / October 2012 Belgrade / New Orleans

Translation from the Serbian

By Biljana D. Obradović