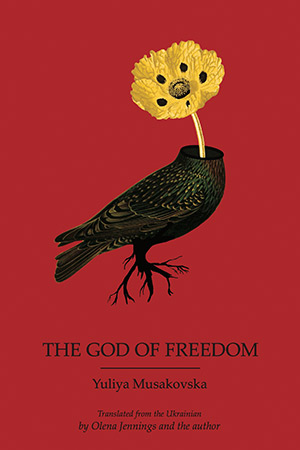

The God of Freedom by Yuliya Musakovska

Medford, Massachusetts. Arrowsmith Press. 2024. 116 pages.

Yuliya Musakovska is one of many Ukrainian poets whose work has been profoundly affected by the war that Russia launched against their country. The God of Freedom, originally published in 2021 and her sixth collection, reflects on the first seven years of the war, which began in 2014 with the invasion of parts of eastern Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea. As in much Ukrainian poetry of this period, war is in the background, tangible as an underlying anxiety, a suppressed trauma, a lurking threat to freedom. Indeed, an inattentive reader may not immediately appreciate that this is a collection of war poetry. In their oblique approach, the poems demonstrate how war seeps into all aspects of life, far beyond the front lines. As her poems addressed to a son or a lover attest, war shapes our most intimate relationships. It casts a shadow over ordinary moments of joy, and yet, paradoxically, makes emotions, experiences, and relationships more intense.

Musakovska’s poems are written in a confident voice that oscillates between gentleness and urgency, vulnerability and irony. The tonal shifts are handled nimbly by the translator team of Musakovska and Olena Jennings, as are the phonetics of the originals (“Friday evening. There’s nothing left to talk about. / A silver-headed serpent of silence slithers out”). Most striking in Musakovska’s work is her imagery, which has shades of symbolism and occasionally surrealism. An intricate system of images—particularly those related to animals and the seasons—provides an overarching coherence as the poems move from the intimate to the political and the philosophical.

Animals, for Musakovska, characterize human relationships. In “The Spartan Boy,” a soldier’s trauma becomes a fox cub in his pocket. His “heart keeps falling out” of the hole it gnaws there. In the same poem, “When the city falls asleep / the black caterpillars of scars wake up. / But only death’s head moths will emerge.” The fable of war trauma is completed thus: “The fox is peering out of your pocket, / licking its lips, recalling what my bird of peace tasted like.”

Seasonal images speak to broader problems. Summer, always on the point of ending, brings guilt over carefree moments in wartime: “Shield this summer with your body from the pain, / from the reckless words, dust, and burn. / Summer, which we once again did not earn.” Autumn, we read in “Shadows,” is a “golden fort” that gives space for reflection and remembering: “Autumn cuts our figures from leaves, rocks us with its finger. / We are mere shadows of our past selves. A taste of late berries.” It is a season of endings without resolution:

in autumn we echo,

unpunished and unforgiven.

Naked like at birth,

swaddled in pain and cold,

we observe the way that autumn

closes the circle.

And the next one unfolds.

While autumn reflects on the past, winter crystallizes pain, as in “Snow”:

A clean page—empty like a white banner,

Be silent, don’t move—let the bruises and sores speak.

In the throat a feeling of birth, sharp and bitter.

A snowflake, a metal star, shuriken,

Stuck in a ragged collar.

It does not melt away.

Spring is a time of rebirth, but it also brings the pain of growth and healing: tree branches, roots, even small birds grow through the body of the lyric subject in ways suggesting both pain and its overcoming. “Falling from the Wheel” describes the winter-to-spring movement as a time “to lock yourself in your shell to let your wounds heal. / Warm up the buds of silk wings under a blanket, / take time to decipher rainbow telegrams of the sun.” The last line gets to the kernel of Musakovska’s spring: “spring copes with its fear – and arrives.”

For Musakovska, fear is a recurring theme. It is a way of being and of thinking (or, rather, of choosing not to think). It is the obverse of the freedom of the collection’s title. “Fear” provides a string of metaphors for this state—an iron hoop around the neck, a disease brought home from war—but we also read that “Fear is safety / which devours freedom / with a pretty mouth.”

It is in warning mode that the collection ends, with a poem showing what happens when we lose faith in the god of freedom and turn to the “God of Submission”:

The god of submission loves gentle calves.

They can be spread like honey and put on a wound.

They will be watching and chewing diligently,

in the grass where a soldier is dying.

The god of freedom loves gentle

calves.

With this cautionary conclusion, the preceding poems’ exploration of the tortures, traumas, dignity, and courage of a society at war begins to make urgent sense.

Uilleam Blacker

University College London