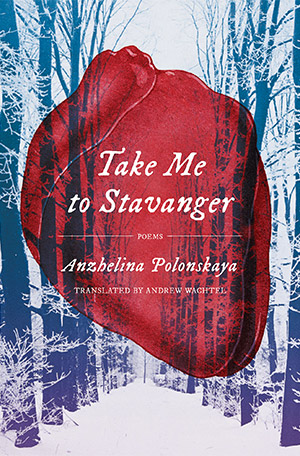

Take Me to Stavanger by Anzhelina Polonskaya

Pittsburgh.University of Pittsburgh Press. 2023. 80 pages.

Pittsburgh.University of Pittsburgh Press. 2023. 80 pages.

Take Me to Stavanger is a collection of poems by Russian poet Anzhelina Polonskaya, who hails from a small town, Malakhovka, located near Moscow. The poems appear in English translation en face with the Russian originals.

The poems are short, lyrical poems of less than a page in length, most around twenty lines long, some with symmetrical stanzas—five stanzas, four lines long. In Russian, they do not have end-rhyme or any particular rhythm. I can see that the translation is more “fluent” than literal, and it captures a sense of mystery, the way that the concrete gives rise to contemplations of the metaphysical and the individual’s attempts to make sense of the world. “I don’t remember summer. Rain” opens with the same words as the title and then moves into a contemplation of how one’s sociopolitical context is ultimately unknowable and unchangeable; the work of the poem is to render and reproduce the feelings of being trapped, helpless, and ultimately filled with self-recrimination.

In addition to exploring one’s ultimate lack of agency, the collection also incorporates themes of isolation and solitude. In “No one. Never,” Polonskaya explores how one comes to terms with the brutal realities that ultimately human connection is ephemeral and waiting for something that is unlikely will only arouse futile hope. It is better to be psychologically preemptive, suggests Polonskaya with a tone of wry resignation: “And if anyone should knock in the midnight darkness / here are twin keys that fit / any lock: / ‘No one.’ ‘Never.’ // People tend not to return.” Similar awareness is developed in the poems “Of Darkness, to Darkness” and “About No One, and About You,” where the people one knows are exhausted leaves that fall into the fire or are carried off by the wind.

Preemptively developing a philosophy of managing expectations, of steeling oneself against disappointment, may seem ultimately self-defeating or nihilistic. However, being emotionally hard or numb is not Polonskaya’s expressed intent. In many of the poems in the collection, she references life’s journey and the accompanying emotions. Language creates a space in both memories and in the heart, as well as an awareness of the fact that consciousness creates a way to simultaneously be with a person via memories and to acknowledge their loss. As she writes in “Farewell for now,” the train of existence “races into time,” and while the passage of time is linear, the mind’s journey is not: “You can’t bring anyone back, nor forget them.”

Other themes and repeated elements in the poems include temperature (cold), loss, nature, and the sense of existing in a boundary region between geographical places, chance encounters, and states of being, with the poem itself imparting the ability to experience both what has happened and what may come to pass.

Susan Smith Nash

University of Oklahoma