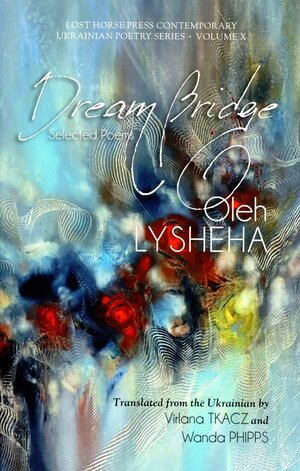

Dream Bridge: Selected Poems by Oleh Lysheha

Sandpoint, Idaho. Lost Horse Press. 2022. 160 pages.

Sandpoint, Idaho. Lost Horse Press. 2022. 160 pages.

In November 2013 I met Oleh Lysheha for the first and last time. During that meeting, we chatted about the United States (where Lysheha spent a whole year on a Fulbright scholarship), the underground Lviv scene of the 1970s and ’80s, the Ukrainian modernist poets of the early twentieth century, and American writers of the nineteenth century. At some point, Lysheha shared this legend (or myth) that captivates my attention still. In 1939, when the Soviets entered Lviv, they authorized the establishment of a union of writers so that Ukrainian- and Polish- and Yiddish-language writers populating the city could coexist on some kind of official level. Thus, newspapers and journals were established, and the publishing industry also began to function in Lviv, printing all kinds of books. Legend has it that one day Bruno Schulz, a Polish-Jewish writer from Drohobych, appeared in the office of Petro Kozlaniuk, a writer affiliated with the newly created union of writers. Schulz gave him a manuscript of a short story he allegedly wrote in Ukrainian. After spending some time on the work, Kozlaniuk’s verdict was adverse: this story won’t be published. A myth, a legend, an exaggeration, this lore of Schulz’s unknown short story in Ukrainian is still captivating. (Upon reflection, this might have been a reworked story of Schulz trying to pitch his original Polish-language work to a newly established venue, interested in works embodying social realism as its true virtue.)

Oleh Lyshesha, born in 1949, had succeeded, without carrying too much or giving it much of a try, in securing a special place in the literary canon of twentieth- and twenty-first-century Ukrainian literature. In addition to being a genuine poet, he was also an outstanding prose writer and essayist, and hopefully, one day, his prose, too, will see the light of day in English translation. His poems are arresting; his technique is demanding, changeable, and progressing; his story as a writer is captivating; and his behavior is extravagant as befits a poet—all in all, features that a great poet might possess.

Lysheha’s formative and decisive years took place in the city of Lviv, once a multicultural and multilingual crossroads, and overlapped with the Soviet Union’s stagnation period, with little perspective and a dull atmosphere of total hopelessness. But there was a cohort of people eager to form a clandestine circle that intellectually and culturally opposed the boredom of daily routine and led nonconformist lives.

When Lysheha was a senior at a local university, studying the English language and literature, shortly before graduation he was expelled for participating in an unofficial literary journal, Skrynia (The Chest). Lysheha had to start a life from scratch. The fact of being expelled from the university closed the doors to any official establishments, which the poet didn’t quite seek anyway. Nevertheless, that expulsion offered him priceless intellectual freedom to create and share the work he cultivated until the end of his life. For most of the Soviet era, his work was thoroughly appreciated, although clandestinely, by a highly appreciative and selective circle of readers and colleagues. It wasn’t until before the collapse of the Soviet Union that his first collection, Zyma v Tysmenytsi (Winter in Tysmenytsia), came out when he was forty. It is represented in this collection by just a few poems, including the blockbuster poem “Song 212”: “There are so many superstars, overgrown with weeds.. / Somewhere Tom Jones // Is still singing about that green-green grass.. // On such a night under the moon among the trees // cinnamon mushrooms // practice choreography.”

The constellation of writers that formed Lysheha as an author and illuminated his path is quite unusual for a poet who lived in those geographical coordinates at that time. His poetry has something of a modernist feel, like that of Ezra Pound (whom he rendered into Ukrainian); then, on a different level, there is a mixed team of heavyweights from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including Henry David Thoreau, Robert Penn Warren, and Sylvia Plath—just to name a few. The Western canon is not, however, the only source of inspiration. Ukrainian literature also influenced Lysheha with its thriving modernist tradition and, specifically, its modernist champion, Pavlo Tychyna. It’s from Tychyna, I maintain, that Lysheha borrowed this idea of playing with punctuation. His landmark double period is succinctly explained by Bob Holman in his thorough introduction: “Two periods is smack between the sentence and the ellipsis,” and two periods “instead of one (1) both emphasize the finality of the sentence while at the same time approaching the eternal on-goingness of the ellipsis’s three (3) dots.”

In the poems collected in The Dream Bridge, we deal with the poetry of a metaphysical poet, at ease with nature (it could have been called eco-poetry if these terms existed back in the day); approaching the daily routine of life slowly; pondering questions at a pace you won’t expect now, deliberating on the eternal that is daily at the same time. Thanks to or because of the heavy anglophone influence those poets made on Lysheha throughout his career, the translators Virlana Tkacz and Wanda Phipps have found a voice that makes these verses sound natural in their translation. The exchange rate the translators found does give a chance to adequately capture the smooth and smothering tone of the poems in English. The reader can delve into this entirely private polyphonic world (being, at the same time, not exclusive but accessible), created by one of the most significant yet not fully recognized poetic voices of eastern Europe of this and past centuries.

Ostap Kin

The Graduate Center, CUNY