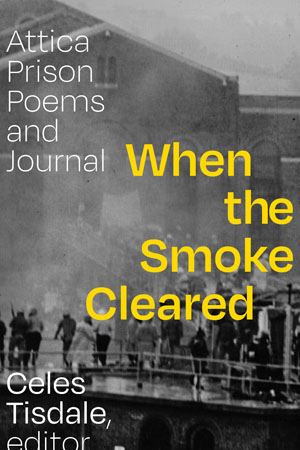

When the Smoke Cleared: Attica Prison Poems and Journal

Durham, North Carolina. Duke University Press. 2022. 142 pages.

Durham, North Carolina. Duke University Press. 2022. 142 pages.

How does one effectively respond to the injustice of state-sponsored violence, especially such violence directed at imprisoned people, numbering roughly 1.9 million in the US today, who lack agency on the inside and a voice on the outside? In September 1972 the now-famous uprising for better conditions and educational opportunities at Attica Correctional Facility was violently crushed by law enforcement, resulting in forty-three dead and ninety-one wounded.

Eight months later, poet, educator, and actor Celes Tisdale from nearby Buffalo, New York, decided that offering poetry workshops was the best way he could respond. Through his connections with the Buffalo Black Drama Workshop and with the support of the New York State Council on the Arts and other organizations, Tisdale led weekly poetry workshops at Attica for nearly three years, during which he listened to the participants’ concerns, helped them find their poetic voices, and grew to have deep respect for them as they did for him. While doing this, Tisdale discovered the power of such work to transform by providing identity and agency on the inside and a voice on the outside. When the Smoke Cleared documents this power, as well as the related process and struggle, through a blend of historical and contemporary texts.

At the workshop participants’ request, Tisdale helped to compile, edit, publish, and promote an anthology titled Betcha Ain’t: Poems from Attica, which included excerpts from Tisdale’s related journal entries; this anthology was published by Broadside Press in 1974. When the Smoke Cleared: Attica Prison Poems and Journal is a republication of Betcha Ain’t with a new preface by Tisdale, now in his eighties, a sharp, comprehensive introduction by poet and essayist Mark Nowak, and additional poems and journal entries from Tisdale’s work in the 1970s. This new collection serves as a valuable glimpse into the beginnings of prison and justice writing programs in the US, especially ones focused on the African American experience, as well as a reminder of the historical and continued importance of such workshops in transforming the US carceral system.

The power of these workshops is shown foremost through the work these incarcerated writers created. For example, “13th of Genocide,” by Isaiah Hawkins, documents the slaughter that ended the uprising in quatrains and begins, “The clouds were low / when the sun rose that day. / For the white folks were coming / to lay some black brothers away.” Much of the work in Betcha Ain’t deals with similar themes of racism and violence, especially related to the recent uprising, in a system that was said to reform. There’s also power in the imaginative space of the poem that gave the original collection its title, “Betcha Ain’t,” which begins, “Hey! / Betcha ain’t / never seen a tangerine sun / kiss / the rolling hills and / mountain valleys of Africa.” A handful of other poems in the collection take on similarly imaginative material and playful tones, and Tisdale’s journal entries as well as letters from workshop participants further attest to the workshops’ transformative power on teacher, students, and institutions.

Nonetheless, difficulties abounded. In Tisdale’s now expanded journal entries, we see the record of resistance and oppressive oversight by the prison administration, low morale and attendance by the participants, political tightrope walking, miscommunication resulting in misunderstandings between Tisdale and his students, lack of funding, road-blocking snowstorms, and, understandably, burnout on Tisdale’s part. (As a volunteer with a prison writing group in Oklahoma, I’ve experienced many of the same difficulties.) And here’s where the contemporary material, especially Nowak’s introduction, adds a lot of perspective on the original publication and related workshops. Nowak studiously outlines the historical context of the Attica uprising, Tisdale’s entry into that world via his workshop, Tisdale’s use of and connection to “the rich history of Black poetry” as well as the contemporary Black Arts Movement, the historical importance of this workshop, and again, the power, both then and now, of such work to effect change.

The relationship between the original publication and this republication and expansion could have been better highlighted in the contents, the new preface, the introduction, and the layout. Admittedly, the existing kaleidoscopic perspective provided by the combination is profound, so much so that I found myself wishing for even more: a timeline; a list of the uprising’s demands; a better sense of why Tisdale stopped going; what happened to some of the more promising writers; and a clearer connection between this workshop and contemporary efforts, such as PEN America’s Prison and Justice Writing program, which cites the Attica uprising as the inspiration for its founding.

What this publication does make clear is that Tisdale’s persistent response to state-sponsored violence, despite the difficulties, cracked the door open for a small group of incarcerated writers some fifty years ago, and their collective daring and work changed lives and perspectives then and continue to do so now. In this sense, even if teaching creative writing workshops on the inside remains fraught with difficulties, the power and agency they engender endures and makes them, as this important and timely collection shows, an important and transformative response to the continual state-sponsored violence of the US carceral system.

Timothy Bradford

University of Oklahoma