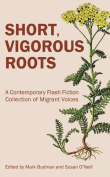

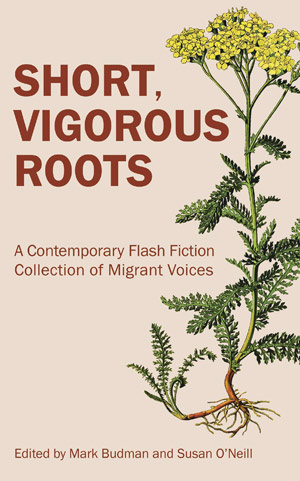

Short, Vigorous Roots: A Contemporary Flash Fiction Collection of Migrant Voices

Portland, Oregon. Ooligan Press. 2022. 160 pages.

Portland, Oregon. Ooligan Press. 2022. 160 pages.

WHAT CAN BREVITY OFFER readers that length cannot? A specific style of intimacy; an intimacy borne out of a glance, or an impending departure. The intimacy of flash fiction, of brevity, is the intimacy of mystery. It is the intimacy of potential. The form is not synonymous with poetry; a contained and glancing short story isn’t the same thing as a lyric instant in a narrative poem, because flash fiction also contains a propulsive narrative arc. The story must hold more, while paradoxically, the story will contain less. Character specificity and interiority drive such works. Works that recall the wisdom of Flannery O’Connor in her Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, essays on the craft of writing. Fiction that is brief relies on an inner coherence in the characters and a quality of the spectacular and specific all at once—why this story, why this day? Such characters have an “inner coherence, if not always a coherence to their social framework. Their fictional qualities lean away from typical social patterns, toward mystery and the unexpected. It is this kind of realism that I want to consider.”

Short, Vigorous Roots is a new anthology of multivoiced, contemporary works of flash fiction. The book is about various and diverse experiences of migration. The flash fiction anthology, as the editors note, “looks critically at what it means to forsake tongues, traditions, and comforts in the hope of starting a new life in another world.” The collection of forty flash works is written by multigenerational authors from countries around the world, including Bosnia-Herzegovina, Brazil, China, Cuba, Lebanon, Mexico, the Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, Ukraine, Vietnam, and beyond.

Many of the most affecting stories in the anthology take place in a specific place and time. In “My First Day in Monterey,” Nina Kossman describes an encounter inside a Safeway, “the nearest supermarket” to where the narrator now lives. “I get something called Havarti. I choose it because it is sliced, and I can eat it in my room without a knife. Cheese in my right hand, strawberries in my left, I stand in line at a cash register when I hear Russian speech behind me. I turn around and see a man unloading groceries from a cart back onto a Safeway shelf, saying to a small blond woman next to him, We don’t need this. And we don’t need that. And that. And that. I can’t see his companion’s face, but from her tense neck I can tell that she isn’t happy with the way he is emptying the cart of all the things she was looking forward to tasting.” In Kossman’s gorgeous story, the scene-work draws the reader closer inside a specific moment, tied to a particular place and time, but also to a particular point of view and, ultimately, the ways that the two women are seeing and relating to each other. This quality of both intimacy and distance moves across the various flash fictions that compose the book, each of which is one thousand words or fewer. The anthology is a space of brevity and closeness; this quality unites the deeply character-driven works.

Some works veer speculative, as in Amit Majmudar’s “Throwing Down Roots.” In Majmudar’s story, a six-year-old child swallows an apple seed in the backyard. “My mom screamed for my dad, and together they marched me by my elbows, like a dissident in the old country, into the backyard. Did I feel it? Was it coming?” The child soon grows roots that lengthen and dig into the “hard Ohio soil where our ancestors had never sunk a spade.” The child sprouts branches and grows plump apples. “The trunk swelled, too, cracking my ribcage. I had lost sensation in my legs by then, and in my chest, and in my arms.”

The chasm between generations presented in a speculative mode in “Throwing Down Roots” is echoed in Ellison Alcovendaz’s “The Last Stand.” The narrator reflects: “I just married a white girl, and nobody cares but my father, the same man who calls himself The Filipino Casanova, which is hard to imagine with his fake teeth and half-burnt face (a chemical attack in a war, he insists).” “She got money?” he asks.” Alcovendaz’s scene-work and dialogue are propulsive, driving and escalating the dramatic tension between father and son. “But I’m already outside,” the narrator thinks, later, leaving his father’s house. “I’m already in my car, I’m already driving to the suburbs in my Jeep Cherokee. . . . I’m already done, I’m already gone, I’m already here.”

In “The Last Stand” and elsewhere, the pain of unease and misconnection between people and generations is amplified by the spareness of the flash form. A strength of brief works, recalling O’Connor, is the narrative power of mystery: the quality, as one reads, of almost but not completely knowing a character, or a world, or a set of meaningful lived experiences. Works of flash are formal rebels that lean away from typical social patterns, toward mystery and the unexpected. “It is this kind of realism that I want to consider,” O’Connor writes. Short, Vigorous Roots is an intimate, liminal work of realism.

The book’s cover image is of the yarrow plant. “When the days get warmer, it returns to lush green foliage and blooms . . . this miraculous little plant is remarkably resilient—as are the characters featured in this collection—making yarrow symbolic of the themes presented in this flash fiction anthology,” the editors write. Short, Vigorous Roots is a work of resilience, and complex beauty.

Kathryn Savage

Minneapolis College of Art and Design