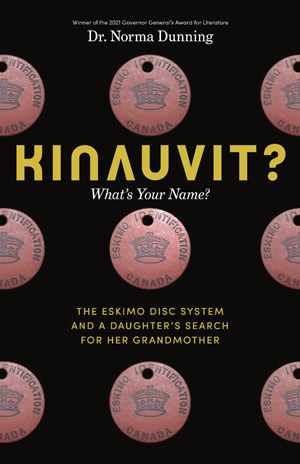

Kinauvit? What’s Your Name? The Eskimo Disc System and a Daughter’s Search for Her Grandmother by Norma Dunning

Madeira Park, British Columbia. Douglas & McIntyre. 2022. 184 pages.

Madeira Park, British Columbia. Douglas & McIntyre. 2022. 184 pages.

COMBINING PERSONAL MEMOIR with cultural history, Kinauvit? reflects Norma Dunning’s experience constructing short stories about Inuit people’s everyday lives outside their northern homeland. Her collection Tainna: The Unseen Ones—deftly constructed and interwoven—won the 2021’s Governor General’s Award for English-Language Fiction in Canada. There, she introduces an auntie “who laughed easy” and said that “residential school was in the past and what mattered was now.” When a child, Dunning’s real-life Auntie Francis “let the word ‘Inuit’ loose into the air” and referred to “the convent” attended with Norma’s mother.

Dunning’s MA thesis—reworked into Kinauvit?—filled the “hole of unease” that followed her for the first forty years of her life and awakened her “sense of kinship.” Her initial “physical rendering” of her ancestry, her application for the Nunavut beneficiary program, consisted of two lines. She didn’t know her mother had a disc/disk number/e-number—didn’t even know the classification system existed for thirty years. Inconsistent naming conventions could explain such unfamiliarity; a more nuanced understanding of how the “Eskimo Identification Canada system slid into existence” emerges with Dunning’s exploration of family history alongside Inuit/non-Inuit relations.

Distinct from First Nations and Métis communities, the Inuit were ruled a federal responsibility by Canada’s Supreme Court in 1939. Ongoing global tensions following World War II (1939–45) culminated in the Cold War with a global view of northern territory in Canada being vulnerable to Soviet expansion, and non-Inuit influence—missionaries, whalers, traders, RCMP—expanded further “under the guise of offering social benefits, commerce, and education.” The outlawing of drum dancing, the disappearance of women’s facial tattooing and the Inuktitut language, and several forced relocations (causing many deaths, acknowledged decades later via the Qikiqtani Truth Commission), all fueled colonization. Dunning’s formalizing of her Inuit kinship counters colonization: “When language, ceremony and spiritual connections are being sliced, outlawed, and categorized as sin, the invasiveness of the colonizer cutting into Inuit daily lives is like watching a slow and painful death.”

She explores the need for tukitaaqtuq (Inuktitut, meaning “they explain to one another, reach understanding, receive an explanation from the past”) and reconnects with her ancestry. Her fiction, too, emphasizes connection; in Tainna, for instance, readers meet the titular protagonist of Annie Muktuk and Other Stories (2017) again. Dunning’s readers expand their understanding of how the historical experience of the Inuit persists in their present-day lives, how history reverberates in the present.

Marcie McCauley

Toronto