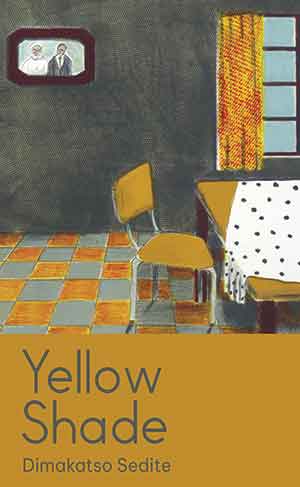

Yellow Shade by Dimakatso Sedite

Makhanda, South Africa. Deep South. 2021. 67 pages.

Makhanda, South Africa. Deep South. 2021. 67 pages.

Dimakatso Sedite’s marvelous debut, Yellow Shade, opens with the poem “Middle-town,” a meditation on the speaker’s origins in a township in Free State, the province at the center of South Africa. Throughout the book, apartheid and its aftermath are left implicit. Instead of referencing the oppressive system, Sedite invests in the lyric details, which nimbly contextualize the poem: “and many songs we sang to make us forget we had no textbooks.” Rather than allow South Africa’s monumental history of racism to dominate the book, to the exclusion of all else, Yellow Shade foregrounds instead the felt experiences of Sedite’s Black speakers. Thus, none of her poems lose velocity through the weight of exposition: Sedite trusts her lyric mode.

Throughout Yellow Shade, this trust generates striking imagery as well as sonically rich lines. The speaker of “Middle-town,” for instance, looks back through the “keyhole of childhood,” at herself and her companions gathering at the preacher’s house after school “to speak more songs, / about Bethlehem, Judea, our cartilage selves breaking locust legs / of his bench.” The consonantal echoes between “cartilage selves” and “locust legs” speaks to the children’s vulnerability—cartilage is more pliable than bone—and yet there’s a joyful dissent against all that ameliorative singing when the speaker imagines the rickety bench legs as a locust.

As Miles Davis once said, “It’s not the notes you play, it’s the notes you don't play.” In “Middle-town,” Sedite’s speaker refuses to name the place and calls it “middle-town” without a capital letter, as if to also refuse the logic of apartheid in which the name of the town where she grew up would limit or deny her future existence. How to write a love poem to a place that almost destroyed her? Calling it “middle-town” allows Sedite to reimagine where her speaker comes from—on her own terms. At the same time, in the poem “Purple dance,” the speaker does name a township, but for its sonic richness: “I grew up with a boy in the backyard of Bochabela, / where boys played chibobo, and chickens ran free.” In this case, the name “Bochabela” echoes the “boys,” “backyard,” “chickens,” and “chibobo” (a children’s game), all integral to the felt experience of that place where “houses spread like flattened cans,” as if the rhythm of the lines lets the poem sidestep the trauma of segregation and enter the creative terrain of “middle town.”

Perhaps the most impressive feat in Yellow Shade is Sedite’s ability to shift perspective. “Soldier in a black dress” speaks in the third person of a widow surviving a husband’s death from AIDS, and “Geelbooi’s homecoming” tells of a man returning home from exile. In the first-person poems, too, the speakers are not necessarily the same “I.” One speaker relates how her children almost died in a shack fire; in “I had plans,” another speaker, as if Emily Dickinson’s “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,” utters the poem from beyond death: “So they folded arms / into a stack of wood; and allowed / darkness to blanket my being.” And yet the unnamed first-person speakers feel connected: sisters, friends, neighbors, or different versions of the self. Sedite’s refusal to name—to draw a clear line between one “I” and the next—becomes an act of openness to others.

Sedite’s poems, even the elegies, speak to the joys of Black plurality. After apartheid, after the AIDS pandemic, what’s left—what her speakers sing of—is not mere survival but connection.

Henk Rossouw

University of Louisiana, Lafayette