Kharkiv

Al Panteliat

When the first explosions begin in the morning, people in Kharkiv do not yet know how to “properly” act. I observe from the window how some residents of my neighborhood hastily pack their belongings into their cars and drive away, while others calmly walk to work.

But over the course of several hours, when the explosions do not cease and we regain access to news (we lost internet as the explosions continued)—people outside start running instead of walking.

In the next few days, practically no cars remain in parking lots, and there are very few people on the streets. It all turns into a postapocalyptic movie.

When, on one of the first days, explosions stop for a moment, we decide to go to the ATM to withdraw cash: there’s an amazing contrast between the empty streets, closed shops, and still-working traffic lights and the windless February day.

A complete silence on the streets leaves an even bigger impression. It feels almost as bad as the bombings, having turned into a “suspense” that time cannot measure. When we reach the ATM, we at last see people standing in a queue. While we wait in a queue, the “suspense” breaks—a long series of explosions, each reverberating under our feet. It is very strange: to stand and wait for your turn to withdraw money while calmly discussing with neighbors where these shells might have come from and where they will land—ordinary life and the new wartime reality have merged into one.

When we hear the air-raid sirens, my family and I grab the backpacks, and our dog, and walk to the nearest basement that serves as a bomb shelter. We stay down there for hours with other residents and their dogs.

Several times a week, this strange journey. Sometimes it is a “voyage to the edge of the night,” because as twilight descends, city authorities do not switch on the streetlights, and the residents keep their own lights off—so that the enemy wouldn’t know where to aim.

I had never seen such pure pitch-black darkness in the city: just like with the silence, any speck of light, whether it’s a car passing by or a man with a torch, breathes a sense of danger.

At last we decide that instead of endless trips to a bomb shelter we should rather do one large escape. On the day we leave Kharkiv, we learn that they started bombing the city center.

As we escape, I surprise myself being able to write poetry “on the go.” I can write while sitting in a bomb shelter, or while driving through a checkpoint, or while watching a building ablaze in front of my page. It is not just my experience, I observe. A great many Ukrainian poets are writing pieces that are in some way connected to the war right here and now. When it comes to my own pieces, I used to be able to theoretically categorize them as “metaphysical” and “cinematographic,” but now only the latter category remains. I observe the same tendency among other poets. This is not surprising. Metaphors are a semitone, and in the current reality there is little place for them.

“I can write while sitting in a bomb shelter, or while driving through a checkpoint, or while watching a building ablaze in front of my page.”

—Al Panteliat

I am still writing in Russian because I think in this language. On the other hand, I intend to translate my future pieces into Ukrainian and never again publish them in Russia. I used to not fully understand stories about why poets like Paul Celan struggled so much to write in a language of a nation that was destroying his people. A language cannot belong to any one nation; a language exists on its own, I thought.

Now, I began doubting that.

Here, I remember the words of one poet—a Russian one, paradoxically—who spoke in English to his American students: “You Americans, you are so naïve. You think evil is going to come into your houses wearing big black boots. It doesn’t come like that. Look at the language. It begins with the language.”

Beginning with February 24, it was as if time restarted. Like in Hollywood blockbusters, it was . . . “Day One,” “Day Two,” etc. Now, everything is perceived as one endless day. When your past is canceled, and you don’t know what will happen in the next few seconds, time stops working as an applied measure. A “mindfulness” of sorts.

Now, the events that happened before the war and, in many respects, the entire past, are perceived in a more clear and structured way.

Somehow it became easier to conduct a certain introspection into one’s life, recall certain details from one or another period of time, understand when, where, and what happened and what you felt in that moment.

It is as if you are a character in some movie and someone “broke the fourth wall” on February 24. Everything looks like your entire life before the morning of February 24 was a prologue to what happened next: I cannot say that the past became cheapened, but it certainly became plainer for me. In films, they often show war in black-and-white and peace in bright colors. For me, it is the exact opposite.

Oleksandr Khodakivsky

Let me tell you how my city changed this month: according to the State Emergency Services, by March 16 more than five hundreds peaceful Kharkivites had died.

From the third day of the war, Kharkiv is constantly bombarded: many people live in the basements of their buildings, in the subway and bomb shelters. Neighbors come home from shelters only to cook some food and to wash. There are also those who wait out the bombs in their corridors and bathrooms.

A strange thing about time in a war zone: everything is experienced much more acutely and brightly, but as more of a given, a fluid fact that cannot be fully understood. That is, during the war it is difficult to objectively assess anything. Because the mind works in a different—nonexistent—dimension.

When war begins, my wife, daughter, and my mother-in-law escape to Poland. I remain in Kharkiv. But soon I cannot endure it any longer and head west with my cat. My first desire after the move to a safe city, after escape, after the journey, is the most basic: to get enough sleep.

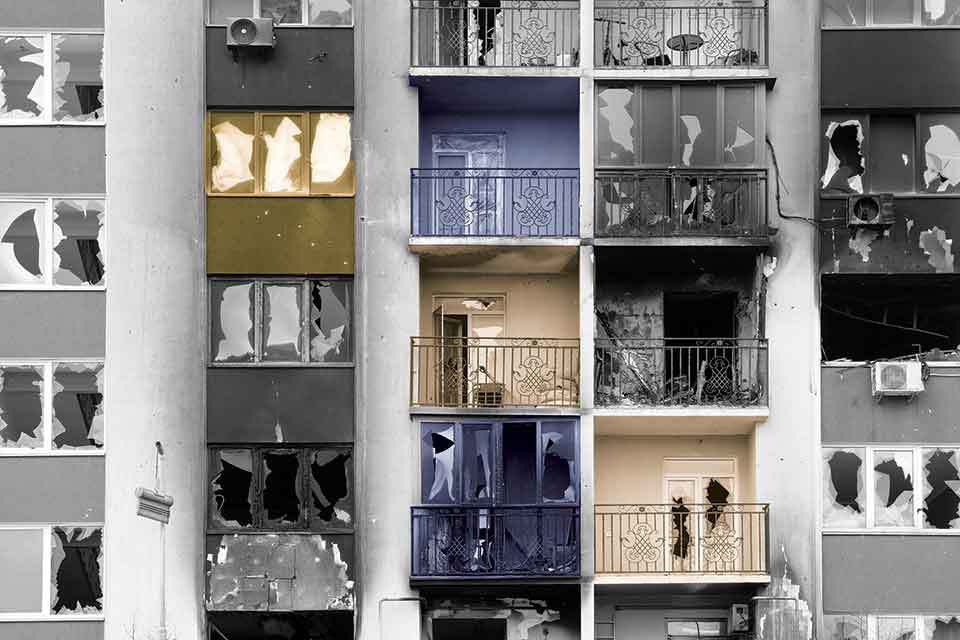

The State Emergency Report says: “The Russian troops destroyed more than 1,500 buildings, including 70 schools, 54 kindergartens, 15 hospitals, 239 administrative buildings, and 1,292 blocks of flats. The city council estimates that 15 percent of the city’s residential housing has been rendered entirely unusable.”

And here is my own report: I am a Russian-speaking citizen of Kharkiv. I now hate everything Russian. The “liberators” robbed me of my language. . . . Now, in the kitchen, in the bedroom, everywhere in my home only Ukrainian is spoken, my poetry is now written in Ukrainian—and all my poems are about this war.

“The city I escaped from, one that I am not seeing right now, suffocates in smoke and ash, stoops to the ground, tired of staring at the sky, but there is no fear.”—Oksana Yefimenko

Oksana Yefimenko

The city of refugees that I am seeing now around me breathes relatively steadily. It sometimes gets seized by another piece of news, or another air-raid siren, but not for long.

The city I escaped from, one that I am not seeing right now—but would want to see with all my being—suffocates in smoke and ash, stoops to the ground, tired of staring at the sky, but there is no fear. That city is suffocating but breathing.

In the city that I am seeing right now, children are playing war and building checkpoints from spruce branches and old furniture that they procured from a barn. These children are growing up very quickly, but they do not understand how difficult it is for them. Perhaps they will understand this difficulty later than children who were, and some of whom remained, in Kharkiv. I have left it behind, but not in the past.

In this month, I understood for myself that war is devoid of semitones when you are squarely in the middle of events. “The gray” stops existing; only the black and the white remain.

Before February 24, I did not know what hatred was, but, as it turns out, this is a normal thing. As is exhaustion, of which I am afraid because in wartime it equals indifference.

Before the war I had an extended break in poetry and creative activity in general—I felt that I had nothing to say. Now, the war exposes a lot I did not know, and I regain poetry: I will keep talking for a long time. Probably, I will continue talking about this for the rest of my life.

It is difficult to speak about the war because it constantly seems that words are trivial. Every single one of us becomes one of the reverberations of the war’s echo. War takes our voices for itself.

Now, it seems to me that everything that happened to me before was an introduction. Or, rather, my attitude to the past is now somewhat similar to the games I used to play when I was a child. My little naïve memories make me smile, and I feel like I am looking at my childhood pictures. But I have seen war, and I am all grown up now.

Victor Shepelev

I see a city that stubbornly tries to live. Old men are playing dominoes in their yard. Children are running in the street (till the air-raid alert). Shops are opening, even a hair salon and hipster coffee place. City workers and neighbors clean up streets and yards from postbombing debris.

I see the scarred city. My district wasn’t bombed too much, so the picture of destruction is rare, and I am still not used to it: you turn the corner, and suddenly the whole building has no windows, and several burned cars are in front of its entrances. People live here; they covered the windows with blankets or construction panels or plastic. Or you walk through the area of old private homes, and suddenly there is a five-meter chunk from the top of an elderly pine tree lying on the street; you look around and see another burnt car, a half-collapsed home, the skeleton of a summer pavilion.

I see a focused city. There is not much argument, not much doubt, not much fear: those who are in uniform go where they should. Those who are without proceed to live, to wait. To help those in need. To calm those who are scared. To be in contact with those who went away. (I am idealizing, but only barely.) It is part of my personal resilience. I repeat this word a lot—resilience—I repeat it in English. I don’t know a perfect translation of it in Ukrainian. I keep repeating the word.

But I want to add that this war began in 2014, and since then everything in my life has changed. Yet this process was slow: in 2014 through 2016 I worked on a large cycle of poems named A Ferry to New Kharkiv and Demolition of Koktebel. It wasn’t mentioning the war directly (rather fantastic/postapocalyptic/metaphorical) but was obviously affected by it in multiple ways. It was written in Russian, which I mostly wrote before that.

Since then, I have never written in Russian and never will.

Another change—immediate—is to my sense of time during the war: there are flashes of the feelings many others talk about: either “it is still February” or “it feels like years have passed.” But most of the time, I am just keeping my routine (the particular items have changed, the approach has not), smoking my pipe in the evening, and planning for the future. My feeling of time still belongs to me. I still plan.

These days, my work as a volunteer consists of bringing food to those in need in my district. It so happened that the part of the district I visit most is where I spent the first twenty years of my life (I now live two kilometers from there and only visit my parents from time to time—or so it was before the escalation). So, almost every day I walk through the yard where I know every corner, every tree, every asphalt route. It hasn’t changed much. Once in a while, I need to go exactly the same way I went from school to my home every day for ten years, twenty years ago. I sit to rest where I sat with my first and only childhood friend when we were both six (we are almost forty now, still in contact, retweeting each other’s angry war tweets).

Memory is weird this way. Just when everybody expects all the past to be lost, it brings you back to it. But it is distant explosions now and an air-raid siren on my phone. I don’t know what else to say.

“I repeat this word a lot—resilience—I repeat it in English. I don’t know a perfect translation of it in Ukrainian.” —Victor Shepelev

Andrii Krasniashchykh

Kharkiv was destroyed during the Second World War—a well-known fact.

Now, compare the well-known pictures on the internet of Kharkiv’s ruins from the Second World War and from today. It is the same picture, only worse.

As of March 30, Russian air raids and artillery bombardments destroyed 1,531 buildings—a seventh of Kharkiv. 1,292 blocks of flats, 70 schools, 54 kindergartens, 16 hospitals.

The city’s historic center is destroyed: Sumskaya, Rymarskaya, Mironositskaya, Yaroslav the Wise Streets, Freedom and Constitution Squares. What will be left of the old Kharkiv with its Ukrainian modernism, Jugendstil, and constructivism after the war?

Only the photographs.

The most horrifying images are not even the ruined buildings. The most horrifying: bodies on the streets after artillery bombardments. Someone was getting water, a bottle is lying near them; an old woman near the bench on the children’s playground; a queue at the store or an aid distribution point. Every day. According to the official statistics only, by April 2, 394 had died in Kharkiv, 21 children.

People changed dramatically. Everyone is very polite, very attentive in the wartime city.

In the first day of the war, our family became separated—we moved in with our parents. My wife with a child and a cat, to the house owned by her mom, where there is a cellar that can be used to hide from air raids. I moved with my parents, to their apartment on the seventh floor of the block of flats. They are seventy-five and eighty-one years old; my father is a survivor of a heart attack and uses a pacemaker, and my mother’s eyesight is poor. They did not go down to the basement because the elevators in their building, just like in all buildings in the city, are switched off, and to go back up to their apartment on foot is impossible for them.

When there was an air-raid alarm, my parents and I sat in the corridor, where there were no windows.

We taped up the window with an adhesive plaster in crisscross patterns, so that shards of glass would not come flying into the apartment.

In the bathtub and other vessels, we kept a reserve of drinking water.

After almost a month of constant shelling, air-raid alarms, and sitting in a cellar, our daughter became closed off and did not speak to anyone.

Now, I can’t read Russian literature. I can’t even look at books by Russian authors. All of it appears to me as lies and falsities. Especially after Bucha. What Russian culture, Russian spirituality can we talk about on such a day?

When it comes to my own writing style, it changed completely. It used to be intricate, baroque. Now, it is short, clipped phrases. Exactly as in info bulletins. Nonfiction interested me little before; now, fiction is dead for me. I write notes about what is happening: about the life of Kharkiv under siege, about the migrants. I record the events, my feelings, what I saw, what I heard. I include the fragments of letters from my friends and acquaintances in these texts. Adorno is right: after Auschwitz, Kharkiv, Bucha, to write like I used to, as if nothing had happened, would be barbarism—akin to what the Russian soldiers are doing.

Of all these months of war, I remember February 24 precisely. The rest are one long day.

My daughter got a school assignment (remotely) to write a narrative on “How [Her] Life Changed Since the War Started.”

She wrote: “On the evening of February 23, as usual, I did my homework and went to bed. When I woke up the next morning, I realized that I was too well rested and the alarm clock did not wake me up. Usually, I get up at 6:30 to catch the school bus. When I woke up, it already was 8:00. I looked at the clock and got very scared.” And then: “At first, when the air-raid siren sounded, we went down into the cellar: me, my mom, grandma, my aunt, great-aunt, and second cousin. The cat was sometimes there too. Days passed like that. Soon, we no longer descended into the cellar and simply switched off the light when the siren sounded.”

“Days passed like that”—that’s who I am now.

“Adorno is right—after Auschwitz, Kharkiv, Bucha, to write like I used to, as if nothing had happened, would be barbarism.” —Andrii Krasniashchykh

Anastasia Afanasieva

We woke up at 5:00 a.m. on the first day of the war because of explosions. We ran from one room to another, we did not know what to do, we packed our documents into bags and then just sat in our kitchen, absolutely confused.

It was still dark out as we were reading on the news: “Putin announces special operation in Ukraine . . .” Many cities were shelled at once. I woke my mom up, who is eighty-one and is hard of hearing, so she was still asleep and I said: “The war began.”

In Kharkiv before the war, neighbors hardly knew each other, except saying “hi” occasionally in the yard. . . . Well, we lived in peace. Many of the silly past conflicts seem foolish now. Like, if someone’s dog pisses on someone’s flowers and someone gets angry. . . . Ha! How funny it is.

After the war started, we all became one. We sheltered in the basement of our building—eleven people, five dogs, later two cats joined. The neighbor I hardly knew before was preparing dinner for everyone. We were bringing chairs, tea, coffee, sugar—everything we had.

Everyone brought to the basement what they had—it could be one bulb, canned food, a carrot, a piece of chicken—well, that is what they had left in their refrigerators. All gathered together made a perfect hot soup, which was cooked by our neighbor for all of us.

If someone became upset or desperate, everyone tried to make them laugh, give them faith. The nine days we spent in the basement were incredible because of this. Then, one by one, after the shelling became stronger and after the warplanes appeared, the planes started to drop bombs on civilians—people began to flee our basement. We stayed for nine days and then left: my mother, my partner, my dog, and my cat. It was an early snowy morning, and the road was sleepy, covered with ice.

We somehow understood that the enemy will attack peaceful people, they will shoot, we did not use any white stickers on our cars, because we thought it would make it more probable for us to be shot by Russians if we met them. We left all our past behind.

We had a bag with us with personal things, two sleeping bags, some canned food, dog and cat food, and my camera. That is all my life for now. It is like you lived your life, and then you find yourself in a purgatory: no past left—and no clear future still.

Every day they continue bombing and shelling our home city of Kharkiv, parks, markets, hospitals, schools, houses, every day peaceful people die just because Russian soldiers decided to strike today. They did not enter the city, they stood at the borders—and used different kinds of artillery. At the beginning, warplanes arrived, and here I get to what was the most terrifying.

The planes: Kharkiv is located very near to Russia’s border, so authorities are not able to warn us in time about a plane coming. It takes three minutes or less for that plane to take off in Russia and to circle over Kharkiv. So, we had a friend in a border village who messaged us a warning: “Plane.” That meant that we had one minute to fall on the floor, close our ears, and open our mouths.

A few moments after his message, we would hear the sound of a plane approaching. It sounds very much like normal planes sound. But then there’s that terrible whoosh of a flying bomb. That sound lasts about one or two seconds—and those seconds were my terror. During those seconds, I prayed. And then came an explosion, mega-explosion, very loud sometimes, as the bombs fell near us. The sound of broken glass: the windows in our house, shattered by a blast wave. As I write this, there is a pain in my chest as I think of those who aren’t with us any longer.

What surprises me: drunks gathering empty bottles in the garbage to make Molotov cocktails. Mothers and kids playing in the yard during shellings—they leave it all to God. Old women with bad hearing who did not hear anything except very loud explosions and kept walking to the stores, because due to hearing loss they didn’t know the warplanes were approaching.

What also surprises me: the speed of losing old habits and life. It’s 5:00 a.m. when one’s old life is totally ruined in one moment—all the habits, work, goals, dreams disappear at once, as if we are teleported to another reality. Former life is a memory in the mist.

What’s terrifying: a building collapsing after a bomb strike. A building where we used to play as kids near where I walked home every day. Blood and bodies near the water source—people died as they were just walking for water. I’m walking my dog in the yard, which is absolutely empty, no people, no city sounds—full silence, interrupted with the sound of far explosions. I am reaching for a knife in my pocket if I see someone suspicious walking toward me. . . . That is what my eyes have seen. Much else is terrifying: videos and photos from cities like Mariupol, Bucha. As for personal experience, such is mine.

We left . . . but there were still people who did not want, or were not able, to leave. They are still there: they help one another, they are united. This is what I will carry from my experience of war: how united, open, fair, generous, and compassionate we are able to be when disaster comes.

As for poetry: I was a poet, writing in the Russian language, born and raised in Ukraine. Many people in the East spoke Russian: it was their native language, it was mine. I was never offended or abused because Russian was my native language. But my attitude is different now: I won’t be able to write in Russian anymore. It is not about hatred of Russian culture or something. It is a very simple human feeling. I am listening to all those phone calls of Russian soldiers, which were made public. And I feel disgusted to speak and write in the same language as they do.

War, I have found, doesn’t have borders, it doesn’t divide time into hours: it is pure time. When the war started, and since then, I feel all of time like one long, whole day. I still do not know what day of the week it is, or what date it is.

The past was cancelled in one minute. Imagine a magic eraser that erases all the text in one moment—and paper becomes white as new snow. No former goals, no former job, no former habits, no former stores we used to visit for food every day, no former walking routes, no former landscapes, no home, no former dreams—pure nothing, clear sheet. You’re born again at the age of forty—only a book of memories with you, a book that you read till the end and there are no new chapters. And you, like a newborn, try to learn to walk again, open your mouth again, speak.

“Everyone brought to the basement what they had—it could be one bulb, canned food, a carrot, a piece of chicken. All gathered together made a perfect hot soup.” —Anastasia Afanasieva

Translated by Dennis Kovtun, Katie Farris, and Ilya Kaminsky