Mimesis and Metamorphosis at the Burggarten in Vienna

AS I ENTERED the Burggarten on a snowy evening, I noticed a life-size statue of a monk when a large midnight-blue butterfly flew into the spotlight and landed at its base. Abraham a Sancta Clara, I read, wondering at this exotic vision at subzero temperatures. My mind moved upward and across the garden to its other end, to the Palmenhaus, an art nouveau glass and metal conservatory and its left wing, the Butterfly House. I briefly considered taking the butterfly back to its tropical paradise behind glass—as if I, too, were the hothouse creature, perhaps frozen or unwilling to be seen in mutual discovery.

The Palmenhaus was hidden behind scaffolding for decades before I discovered a rack of formal dresses and shoes for rent, music for dancing floating out into the summer night while couples glided on its open floors. This time, it is April, and the weather seems unsure of how it would be received. To quote Abraham a Sancta Clara, German preacher of the Baroque era: “The human being is like the April weather, which is soon beautiful, soon wild, . . . soon trickling, soon snowy, soon flowery, soon clovery.”

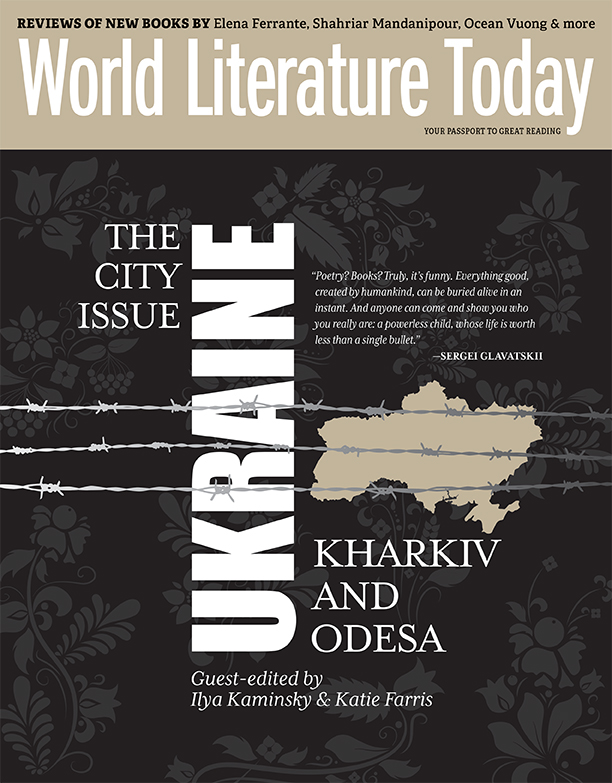

In the projection room of the Butterfly House, I congratulate Sylvia Petter, Austrian-born Australian writer and owner of independent publishing effort Flo Do Books, on the reading and launch of the German edition of Ed’s Wife and Other Creatures. Vanessa Gebbie, the Welsh author, and the book’s translator, dan*ela beuren, stand at one end of the quickly filling room.

Flash-fiction pieces and delightful illustrations by Lynn Roberts portray Ed’s wife, Suze, as various exotic creatures in the fascination of the other, unknown though familiar and loved—to be described again and again. Sometimes Ed sees his bride as a butterfly, “something brushed from his wife to his fingers: the finest dust.” I think of Friederike Mayröcker’s poem “what I call you when I think of you and you are not there”: “my forest strawberry / my sugar lizard / my consolation prize / my silk spinner . . .” (my translation).

My eyes glide over the room. A large poster of a caterpillar, spiky fuchsia hair, and a flower with the same color, titled Mimesis; the flower imitates the poisonous caterpillar’s hair.

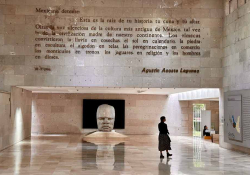

Later, I walk out of the Palmenhaus and across the Burggarten, its variety of rare old trees, a small pond with a statue of Hercules fighting the Nemean lion for its skin in another act of protective mimesis. Travelers, students, and families dot the green lawn where graceful white Lipizzaner mares and foals from the Spanish Riding School are sometimes corralled in summer.

In the 1970s, a people’s movement to liberate the Burggarten from its imperial isolation opened it for all to lounge in the grass under rare trees planted by Maria Theresia’s emperor-consort. Some read, others write, play music, or take photographs with their mobile phones.

The Burggarten is a palimpsest of passages, of personal and communal history. At its outward end, a statue of arguably the most famous Austrian, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, stands, bent gracefully, fingers resting on a musical manuscript as he smiles down at chairs and benches arranged in a small circle.

Beyond the wrought-iron and gold-tipped bars of the gate, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is seated on a massive monument. He gazes at ease over traffic. A horse carriage, a Fiaker, trots past, the driver pointing out sights of interest. Across the Ringstrasse, Friedrich Schiller stands calmly looking over to his contemporary. From their historic height, both of these great German writers seem to watch over cultural and literary movements in Vienna’s inner district around the Burggarten.