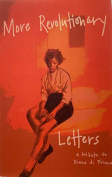

My Hollywood and Other Poems by Boris Dralyuk

Philadelphia. Paul Dry Books. 2022. 69 pages.

Philadelphia. Paul Dry Books. 2022. 69 pages.

A little over halfway through Boris Dralyuk’s new collection of poems, in one of its many sonnets, the reader meets a beguiling but familiar image: a man sealed in the dark belly of a giant fish, encountering the moldering traces of those ingested before him, and gradually losing grip of his senses. This is Jonah—so the poem’s title tells us before we begin—and in the halting iambs and clever slant rhymes of the first eight lines, his mythic plight is introduced with a wry realism that sits us right down in the “scales and slime” of the piscine prison. But as the poem moves into its concluding sestet, a delicate and meaningful shift in tone occurs—the lines smooth themselves out, the rhymes sharpen and clarify, and the implications of Jonah’s predicament alter. The trick with Dralyuk’s Jonah is that he becomes a potent if darkling figure for the émigré: a hero for whom the whale belly is no three-day stopping place but, just possibly, an everlasting home. Inside the beast, the trial, it turns out, is not one of penitence or obedience but of endurance, of loneliness, of the stranger in a truly strange land.

This Jonah-as-exile is less a surprise than an early apotheosis, coming where it does in My Hollywood, since the volume’s thoroughgoing motif is one of displacement and the displaced: phantom geographies, absent presences, existential superimpositions, all manner of flickering mediations abound. As with the iterations of this theme in many of the book’s other poems, the beauty of “Jonah” is that Dralyuk is straightforward in his wish to make exilic grief and nostalgia sing: in the stillness of the foreign innards, lulled by “the rhythm of the tide,” Jonah finally heeds the call to give voice to his ordeal (we’ve been told “he hadn’t written anything in years”), and in the sonnet’s final, truncated line, he composes a psalm. The best rejoinder, it seems, to the inexorable injustices of space and time is the poetic utterance.

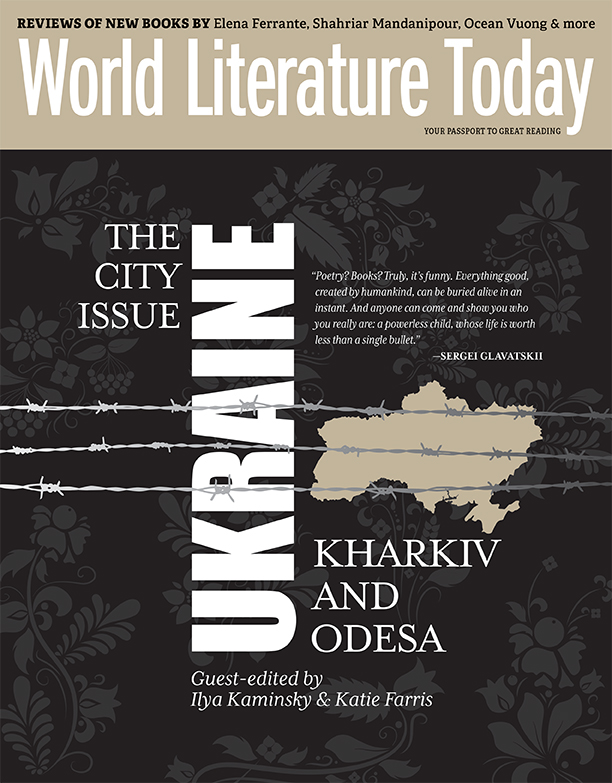

Dralyuk was born in Odesa and came to California with his family as an adolescent in the 1990s, growing into adulthood in the vast, multifarious Russian-speaking community of Los Angeles. The essence of this origin story touches all levels of the volume’s compositions. Duality is the fundamental mechanism of tension: the past haunts the present (although its former existence often feels profoundly impossible) and the forsaken homeland is uncannily close at hand in the new one. For this sort of cultural and geographic projection, Los Angeles—and specifically Hollywood—turns out to be the perfect screen, capacious and expressive enough to host a variety of characters, sets, unexpected encounters, both real and imaginary, a land already rife with infinite doubles and stand-ins.

An example: the book opens with an eponymous triptych, “My Hollywood,” made up of three intricately connected Onegin sonnets, each excavating in the evanescent Hollywood landscape figures of transient prominence and inevitable disappearance. The first poem of the triptych, “Aspiration,” ironizes the title (another irreconcilable duality: ambition into thin air) of the unremembered monument to Rudolph Valentino, an Italian émigré, that stands in De Longpre Park—prior to a 2020 retooling by the city, one of Hollywood’s less savory green spaces. In the poem’s conclusive rhymed couplet, the “clacking” of a crow above the statue invokes a film projector “slowly going dead.” The second, “The Flower Painter,” is an elegy to Paul de Longpré, a French oil painter who found renown after moving to Hollywood in 1899 and became the namesake of the previous poem’s park and the avenue on which it is located. Here it is De Longpré’s Mission Revival mansion and legendary flower garden, both destroyed by developers in the 1920s, that are lamented, their former glory recurring cruelly in the name of a cheap apartment building and the “scruffy rose bush” that preens in front of it. The triptych’s third member, “The Garden of Allah,” focuses these memento mori: its first ten lines mourn the slow passing of coherent daily commerce in Hollywood’s Russian neighborhood, its shops unfrequented and closing, rents rising. Dralyuk then reaches far back into the neighborhood’s past, conjuring the Yalta-born silent screen actress Alla Nazimova, one of the best known early twentieth-century Russian-Hollywood émigrés and, in a sense, also a former resident priced out of a once comfortable life. From 1919 Nazimova was the mistress of the opulent Garden of Alla (a profane play on names; she added the final “h” only later), a private estate on Sunset Boulevard that she eventually converted to an inn with rental villas. When her film stardom faded, she sold the property and eventually spent her last days as one of its paying tenants; the poem’s last four lines follow her from her poolside “private Black Sea beach” to the lonely, rented bungalow. These specifics of urban topography and occupancy, as in much of My Hollywood, operate as a tangible evidence of the unseen, spiritual dislocations of the less eminent subjects who sometimes appear in the poems, living, as Dralyuk writes in one of the book’s shorter lyrics, “like momentary noise.”

My Hollywood is Dralyuk’s first collection of original poems and is particularly pleasurable as an opportunity to meet a poet whose skill with form and voice has been emphatically established in a wide-ranging output of translations of Russian and Ukrainian writers. He may now be the most prominent young translator of Russian literature, and is certainly the most prolific, having published in the last several years high-profile prose translations of Babel, Zoshchenko, Tolstoy, and others, as well as a host of poetic translations that range from Zhukovsky to Fet to Mandelstam to Vysotsky, and many besides. My Hollywood benefits from this intimate relation to literary legacy; there is a richness and confidence that can be felt in the author’s deft movements between forms, his expertise with meter, and his shrewd employment of the epigraph.

This is also evident in his inclusion of a series of new translations of five little-known Ukrainian and Russian émigré poets. These poems precede, like a ghostly fore-echo, Dralyuk’s own overlaying of a spectral Slavic home onto the Californian landscape. Vladimir Korvin-Piotrovsky’s 1961 poem “We’re Going Fishing” presents this most poignantly: after describing a sublime early-morning drive through the Mojave Desert, toward the Colorado, he summons and mourns, “O Russia—you’re so far away now / that I can never part with you.”

The appeal of Dralyuk’s poems is broad: admirers of classical poetic form will find much to study, students and readers of russophone literature too. Should it perhaps be required reading for all adoptive Angelenos? Readers sensitive to any form of migration will certainly appreciate its figures. I imagine too that many will be drawn to the thin volume simply by the prettiness of its refractive cover. But it is Dralyuk’s ability to subtly connect the experience of the émigré to the inevitably more universal theme of death—the ultimate answer to the question of residency, the ultimate emigration—that gives the book its most permeating and consolatory value.

Dustin Condren

University of Oklahoma