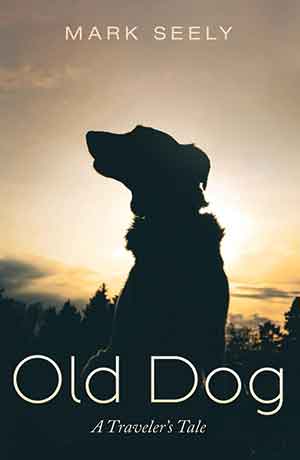

Old Dog: A Traveler’s Tale by Mark Seely

Eugene, Oregon. Resource. 2022. 221 pages.

Eugene, Oregon. Resource. 2022. 221 pages.

THIS IS A TOUCHING book, a moving gift when one is sorely needed. Old Dog is the life story of a dog and also a meditation on that cornerstone, fact-of-life institution, domestication. His history unfolds throughout the book. Among his reminiscences of often very vivid ups and downs, his connections with other dogs and with humans, the presence of domestication often lurks nearby. Its various faces, its force fields are expressed through lives that might have been led in quite different, freer ways.

Old Dog’s life has been a memorable one: his early years with a human family, almost two years tied up and deprived, near-death in an animal “shelter,” running with a pack of feral dogs, and finally his time of rest with the author of this book, among other episodes.

Seely’s work can be thought of as a companion work to Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael. The dialogue that the gorilla Ishmael conducts is instructive, in a basic way, as to the dynamics of the domesticators and the nondomesticators, the “takers” and the “leavers.” After Ishmael, Quinn soon went off the rails, veering toward obscure or liberal efforts. Seely seems in no danger of that trajectory. His powerful Civilization Heresies (2019) was a marvelous blend of the personal and the analytical, comprehensively dissecting the malady we call civilization with passion and depth. Old Dog takes that critique to a new level.

Seely deepens the analysis and extends it, doing so by means of the intimate and personal. I am so struck by how heartfelt his prose is. Old Dog is a combination of voices, exquisitely rendered. Seely’s field is psychology, which seems to give him a nuanced sense of how a dog and the people in his life think and feel.

Of course, the dog has no “actual” voice, since he doesn’t live in the ethos of symbolic language. Dogs and humans cannot speak to each other, and this reality is explored in a lovely, probing way. Communication, it seems, is no way confined to symbolic expression. Old Dog succeeds on more levels than one and can be enjoyed as such. Seely puts it this way: “As a consequence of Old Dog’s ability to navigate both the world of dogs and the symbolic world of humans, he ended up spending a lot of time in his head, lost in contemplation, reviewing memories, and reflecting on various insights he had about the human condition and the world more generally—insights that he would never be able to express outwardly.” His odyssey includes encounters with the homeless and the odd world of the technosphere. In fact, his dog’s-eye view sheds light on many aspects of modern life.

The crisis of today has almost immeasurable dimensions. Its grief-filled destination, the death spiral, threatens life itself. Domestication, spreading throughout the planet for just the past ten thousand years, is the key to where we’ve ended up. Control, ever more control, internal and external. Freud called domestication the basic cause of neurosis, of unhappiness.

Seely, in passing, points to a different direction: “Civilized humans—and civilization itself—are the result of successful self-domestication. The non-existent borders and boundaries that are seen as solid and obvious by the civilized are the walls of containers, the borders of literal corrals that keep people from escaping into the wildness that beckons them from the other side.”

Coming to grips with the mainspring of terminal civilization, domestication, is nothing less than what Old Dog gives us.

John Zerzan

Eugene, Oregon