The Winter War by Philip Teir

Tiina Nunnally, tr. London. Serpent’s Tail. 2015. ISBN 9781781254882

I’m seldom sad to have finished a book. The Winter War is one of those rare novels that leave you wishing there could have been an extra hundred pages or so. Philip Teir’s characters are all endearing, bar one intended to be a snobbish, unbearable figure, and Teir’s heroine is so likeable it makes you wistful you will never be able to meet her in the flesh.

I’m seldom sad to have finished a book. The Winter War is one of those rare novels that leave you wishing there could have been an extra hundred pages or so. Philip Teir’s characters are all endearing, bar one intended to be a snobbish, unbearable figure, and Teir’s heroine is so likeable it makes you wistful you will never be able to meet her in the flesh.

The novel follows the lives of half a dozen characters, mostly from one family, through the winter months in Finland, Manila, and England. The title, which refers to the conflict between Russia and Finland at the start of World War II, keeps you waiting for a family feud that never really takes place. In that sense, it’s a bit of a Waiting-for-Godot red herring. Let’s not forget, though, that the Winter War was actually not a bloody war of attrition.

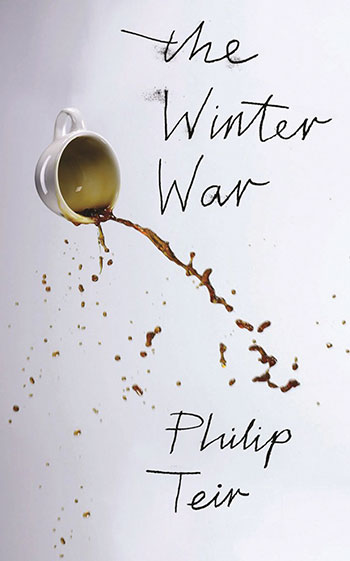

The tension that escalates between Max and his wife, Kristiina, peaks shortly after his sixtieth birthday, but it is resolved in a way one expects Scandinavian conflicts to end: with a few clenched words and a sensible outcome. That coffee cup you see flying on the dust jacket never actually gets hurled through the air. It, too, is merely a metaphor for a much more subdued desire to explode. Do not expect a Swedish-Finnish love story in Bergmanian or Strindbergian mode. This does not mean that Teir eschews overwhelming emotion. Russ, the young art student in love with Eva, the heroine, declares his love in such an incoherent manner that he speaks “almost like a witness to an accident who was still trying to sort out in his mind everything that he’d seen.”

Early northern reviewers have tended to compare Teir to anglophone writers like Alan Hollinghurst and Jeffrey Eugenides, and one can see how The Winter War could work well alongside Eugenides’s The Marriage Plot in a course on that theme, but Teir’s strengths are not the same as the American writer’s. Teir’s characterization of the overpretentious, demeaning Malik as one of the heroine’s potential husbands-to-be hardly makes it surprising that she chooses the other candidate, despite the fact that he seems more puppy than man. The use of a third suitor, as in some of Thomas Hardy’s marriage plots, would have complicated the situation in emotional and philosophical terms, but that might have undermined the heroine’s capacity to surprise us at the end. One of Teir’s fortes is ellipsis, a subtracting technique that even time-honored writers could use more often. He is adept at plunging straight into the heart of a conversation and blurring our bearings before things snap into focus. His use of off-page action makes you sit straight in your seat.

All in all, it’s a delightful read that keeps you gripped by Teir’s narrative and intellectual wherewithal. The novel contains thought-provoking ideas on modern art, sociology, sexuality, marriage in the twenty-first century, aging, the Finnish inferiority complex, and the hamster as metaphor. The sheer book-traveling pleasure of encountering Finnish names like the poetically umlauted waters of Töölö Bay is in itself enough to keep you turning the pages.

Erik Martiny

Paris Sciences et Lettres