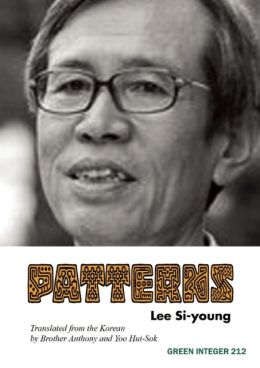

Patterns by Lee Si-young

Brother Anthony & Yoo Hui-sok, tr. Copenhagen / Los Angeles. Green Integer. 2014. ISBN 9781557134226

This hefty pocketbook, Patterns, spans and selects from Lee Si-young’s ten previous collections and maps the career of a wandering humanist actively making sense amid the flux and chaos of competing, shifting ideologies (from colonization, civil war, and military dictatorship to industrialization, then rampant neoliberalism). Born in 1949, a year before the Korean War, Lee scans an increasingly unrecognizable homeland; his poems are often ironic, humorous bucolics seeking to stabilize sites too quickly disappearing or disappeared. As his translators assert, he is “an intimate seer” and pliant-minded cosmopolitan participating “in the cosmic task” of glimpsing, naming, and perhaps purifying a particular and situated dialect.

This hefty pocketbook, Patterns, spans and selects from Lee Si-young’s ten previous collections and maps the career of a wandering humanist actively making sense amid the flux and chaos of competing, shifting ideologies (from colonization, civil war, and military dictatorship to industrialization, then rampant neoliberalism). Born in 1949, a year before the Korean War, Lee scans an increasingly unrecognizable homeland; his poems are often ironic, humorous bucolics seeking to stabilize sites too quickly disappearing or disappeared. As his translators assert, he is “an intimate seer” and pliant-minded cosmopolitan participating “in the cosmic task” of glimpsing, naming, and perhaps purifying a particular and situated dialect.

Indeed, this is a poet prepared to stand up for values “squandered in the course of modern Korean history.” Lee undertakes an encompassing flânerie, exploring places where “gun-smoke never clears”; we see curfews, underground interrogation rooms, and police approaching civilian protesters “as enemies”; comradely magpies nestle beside blue-skulled monks, and laden trucks veer dangerously along riverside highways; in downtown Seoul, a “63-story building” shines its “dazzling gold,” while villages vanish under fog and then suburbia; fifty years after liberation, the poet wonders how to live in a place where “lilac grows in lands where human flesh is food.”

In the book’s eponymous aphorism, we understand the enormity of Lee’s quest: “Leaves gently fall from trees onto sidewalks. / Once someone tried to follow the leaves’ shadows.” Is the poem an ode? An elegy? A confession? So often this poet’s excursions burst through historical spaces to momentarily peer into magnitudes; so many of the poems in Patterns deepen particular apprehensions toward virtuosic resonance, which Lee hopes will enter his readers: “Like a spark, / no, like a first whole-hearted uttering of love.”

One senses this is not a libidinous poetics of erōs, though, but the purview and philia of ethical enactment. In older places of “scrap-merchants, taffy-vendors, junk sellers, / day-laborers,” we see communities mobilized and swarming, often displaced and looking for connection, for ways into the surefootedness of well-being. Sometimes grim, always astonishing, Lee’s poems are three-dimensional expressive snapshots; his meditative reflections act as desperate ontological encounters that never lose sight of either humans or their hegemonies.

Dan Disney

Sogang University, Seoul