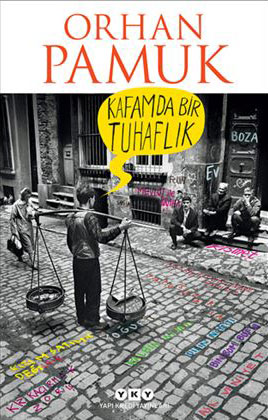

Kafamda Bir Tuhaflık by Orhan Pamuk

Istanbul. Yapı Kredi Yayınları. 2014. ISBN 9789750830884

Turkish Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk’s ninth novel, Kafamda Bir Tuhaflık (A Strangeness in My Mind, forthcoming in English translation in fall 2015 from Knopf) chronicles the life of an eccentric street vendor, Mevlut, whose enduring passion is to sell the long-forgotten Ottoman drink boza in Istanbul. “I will sell boza until the end of time!” declares the protagonist of this bildungsroman who lives in the strangest of times and in the strangest of love stories. Narrated by multiple characters, between 1969 and 2012, the novel explores Pamuk’s persisting questions about solitude, belonging, happiness, and poverty. Unlike his Museum of Innocence (2009; see WLT, March 2010, 67) or Snow (2004; see WLT, Jan. 2005, 109), however, this novel shows little interest in the East/West question, and for the first time Pamuk narrates his beloved Istanbul primarily though the eyes of a working-class Anatolian.

Turkish Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk’s ninth novel, Kafamda Bir Tuhaflık (A Strangeness in My Mind, forthcoming in English translation in fall 2015 from Knopf) chronicles the life of an eccentric street vendor, Mevlut, whose enduring passion is to sell the long-forgotten Ottoman drink boza in Istanbul. “I will sell boza until the end of time!” declares the protagonist of this bildungsroman who lives in the strangest of times and in the strangest of love stories. Narrated by multiple characters, between 1969 and 2012, the novel explores Pamuk’s persisting questions about solitude, belonging, happiness, and poverty. Unlike his Museum of Innocence (2009; see WLT, March 2010, 67) or Snow (2004; see WLT, Jan. 2005, 109), however, this novel shows little interest in the East/West question, and for the first time Pamuk narrates his beloved Istanbul primarily though the eyes of a working-class Anatolian.

Although somewhat reminiscent of the poet Ka in Snow, Mevlut is not one of Pamuk’s typical middle-class Istanbulites. Severed from his village in Konya and his mother at age twelve, he has to join his father and uncle in Istanbul. Tormented by long work hours and loneliness, he finds himself amid the military coups of 1971 and 1980, Kurdish and Alawite conflict, nationalist extremism, and, above all, with a bitter father. When he is finally saved by the love of Samiha, a girl he meets once at a wedding and writes love letters to for three years, he is tricked by his cousin into eloping with the wrong girl, Samiha’s older sister, Rayiha. All this time, Mevlut confesses that he harbors a “strangeness in his mind,” evoking a line from Wordsworth’s The Prelude.

Pamuk’s tender and compassionate narration describes an inborn strangeness in Mevlut—which is at the heart of the novel—but this condition is equally forged by the transformations of late-twentieth-century Turkey. Uneducated and without capital—like most immigrants in Istanbul—he works odd jobs as a parking lot security officer, ice cream seller, rice vendor, lottery inventor, and debt collector. Although Turkey gets more politically and economically divided in the 1980s, Mevlut declares his independence and lacks any form of class consciousness.

A Strangeness in My Mind is imbued with ornate insights into the changing urban landscape of Istanbul and economic character of Turkey: the birth of chain restaurants, supermarkets, malls, factories, bottled drinks, mass-produced foods, the emergence of real-estate moguls, a skyline in Istanbul, the enclosures of the shantytowns, the economic consequences of military coups, and the rise of the nouveaux riches. Amid this dizzyingly rapid change, Mevlut remains as outdated yet unchanged as the boza he sells, missing opportunities for entrepreneurship and apathetic to becoming a wage earner. He treads the streets of Istanbul, catering to the palates of a few dedicated boza drinkers, devoid of material longings, comfortable in his solitude, like a dervish. His voyeuristic tendencies, spiritual wanderings, enigmatic naïveté, and indifference to materiality make Mevlut a subject of mockery among his opportunist friends. But this strangeness also shields him from the tyranny of time and ambition. His bohemian habits might be perplexing, his career choices inexplicable, yet, undoubtedly, he is one of the most sui generis, unforgettable characters in Pamuk’s oeuvre.

Iclal Cetin

SUNY at Fredonia