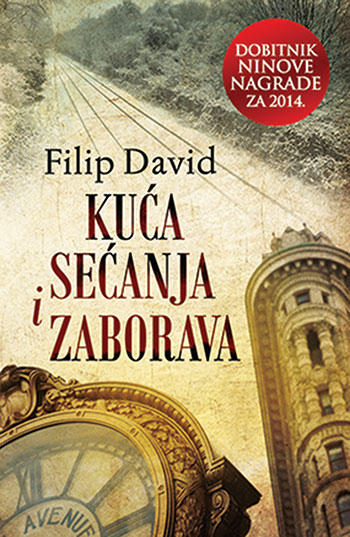

Kuća sećanja i zaborava by Filip David

Belgrade. Laguna. 2014. ISBN 9788652117499

Over the past decade, several excellent post-Yugoslavia novels have been published on genocide and the Holocaust. This indicates a strong writers’ need for reconstructing the past and analyzing the present. Filip David is a renowned author, known and translated abroad. What distinguishes his new novel, Kuća sećanja i zaborava (The house of memories and forgetfulness), from Bosnian and Herzegovinian (Dževad Karahasan, Igor Štiks) or Croatian (Daša Drndić) writers is the opening theme of evil, its constantly changing form and extent in a wider context.

Over the past decade, several excellent post-Yugoslavia novels have been published on genocide and the Holocaust. This indicates a strong writers’ need for reconstructing the past and analyzing the present. Filip David is a renowned author, known and translated abroad. What distinguishes his new novel, Kuća sećanja i zaborava (The house of memories and forgetfulness), from Bosnian and Herzegovinian (Dževad Karahasan, Igor Štiks) or Croatian (Daša Drndić) writers is the opening theme of evil, its constantly changing form and extent in a wider context.

The story about evil begins with Albert Vajs in the twenty-first century, with the agonized sound of a train. We soon discover the reason why that sound has been haunting Vajs for six decades. During World War II, his parents threw Albert and his younger brother from the train to Auschwitz in order to save the children’s lives. Albert never succeeds in finding his brother. A German family helped Albert to survive, but he ran away because he wanted to keep his identity. Guilt will follow him the rest of his life. It becomes another name for the pain of remembering, or the pain of truth.

In the confessions of numerous Jewish children who escaped the Holocaust and hid their identity, the conflict between memory and forgetfulness is revealed as an illusion. While warning us of the consequences of the choice between what to remember and what to forget, David suggests a new dialogue between memory and forgetfulness, a need for a new language for understanding evil. That is why in a literal “House of Memories and Forgetfulness,” Albert cannot choose the button for erasing his recollections of his brother, father, and mother.

The writer masterly connects different stories, Jewish legends, myths, literary allusions and keeps up their rhythm. To picture the reality and to comprehend the nature of evil, David uses and combines various documentary confessional forms from the past (diaries, letters, messages, interviews) and present (newspaper articles, medical and criminal reports) with dreams, hallucinations, fantastic visions, nightmares, and hope. The essayistic parts on evil and violence may serve as a literary connection to the books by Tzvetan Todorov (Facing the Extreme, 1996) and Amartya Sen (Identity and Violence, 2006). In an age when news all around the world is full of evil, national and religious conflicts, wars, and terrorism, David, himself a surviving witness of the Holocaust, wants us to remember that “(our) world is based on human solidarity and individual conscience.”

It is not without reason that the central episode of the novel is the one about Miša and Kosta, about love and humanity, truth and morality. Significantly, during diverse interactions with the world, many male characters of David’s novel cry. This purifying power of the body makes human suffering more visible and at the same time points out what Todorov underlined, that “humanity has not improved and still refuses, on the whole, to hear the lesson from Auschwitz.”

Svetlana Tomić

Alfa University