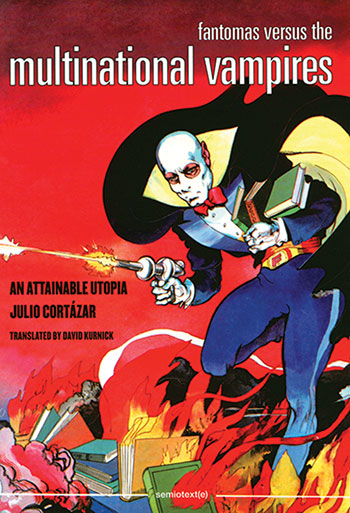

Fantomas Versus the Multinational Vampires: An Attainable Utopia by Julio Cortázar

David Kurnick, tr. Los Angeles. Semiotext(e)/MIT Press. 2014. ISBN 9781584351344

In 1975 Argentine writer Julio Cortázar returned home to Paris from Brussels, where he had been participating in a meeting of the Second Russell Tribunal, an international body charged with investigating human-rights abuses in Latin America. Later that year, Cortázar’s novella Fantomas contra los vampiros multinacionales was first published. Now, at last, Semiotext(e) has made it available in English.

In 1975 Argentine writer Julio Cortázar returned home to Paris from Brussels, where he had been participating in a meeting of the Second Russell Tribunal, an international body charged with investigating human-rights abuses in Latin America. Later that year, Cortázar’s novella Fantomas contra los vampiros multinacionales was first published. Now, at last, Semiotext(e) has made it available in English.

The novella opens with “the narrator of our fascinating story,” unnamed but clearly Cortázar, in Brussels where, having completed work with the tribunal, he rushes to catch a train to his home in Paris. To while away the upcoming journey, he buys “The Mind on Fire,” an issue of the Mexican comic book about a caped, masked superhero, “Fantomas, the Elegant Menace.”

As he reads, the narrator discovers Fantomas’s mission: to find and thwart an evil genius who is destroying the libraries of the world and threatening writers with death if they ever again put pen to paper. In the comic, Fantomas contacts many living writers—including, to the narrator’s (and our) surprise, Julio Cortázar and American critic and political activist Susan Sontag.

In the novella, Sontag contacts “our narrator” (Cortázar), urges him to finish the comic then call her back, and mentions that she expects to talk soon with Fantomas. Before long, Fantomas, Sontag, and Cortázar are working together to thwart an evil far greater than the comic’s “bibliocide.”

If this seems complicated, just wait. In our world there is a (fictional) character named Fantomas. He first appeared as a criminal mastermind (named Fantômas) in a series of forty French pulp novels published between 1911 and 1947. In 1969 he was resurrected as a gentleman thief and defender of the downtrodden in the Mexican comic-book series Fantomas, la amenaza elegante. In his novella, Cortázar includes panels and pages taken directly from issue 201 of this comic, “La inteligencia en llamas” (February 1975).

Readers acquainted with Cortázar’s work will find the storytelling in Fantomas and the Multinational Vampires familiar. In his dauntingly experiential novel Rayeula (1963; Eng. Hopscotch, 1966), Cortázar used collage as a structural principle for pure prose. He later extended this technique to visual material, such as engravings, designs, and photographs in La vuelta al día en ochenta mundos (1967; Eng. Around the Day in Eighty Worlds, 1986) and Último Round (1969). And by 1975 Cortázar had published an overtly political novel about Latin American politics, Libro de Manuel (1973; Eng. A Manual for Manuel, 1978), which included extracts from newspaper articles.

But the tone of the later work is nothing like the playfulness of Fantomas and the Multinational Vampires. To some, addressing human-rights abuses in this way, via a character born of French pulp novels and Mexican comics, may seem incongruous or even inappropriate. But such is Cortázar’s way: in an interview in the Paris Review, he remarked, “For me, literature is a form of play . . . it’s a game, but it’s a game one can put one’s life into. One can do everything for that game.”

The production values of this slim book are up Semiotext(e)’s usual high standards. David Kurnick’s translation—and especially his essential afterword—are first-rate. In an appendix, Semiotext(e) includes excerpts from the findings of the tribunal.

Michael A. Morrison

University of Oklahoma